- Home

- ‘Leaders, we must be bold to save education’

‘Leaders, we must be bold to save education’

New terms are always a time for optimism. And rarely in education have we craved optimism more. We are living, it seems, through a jaded, bewildered, deeply cynical era. Or perhaps I just look at Twitter too much.

But history reminds us that there was a similar national mood some 75 years ago. In 1944, a nation wearied by war, riven by anxiety, uncertain of its future, had similar cravings that the future needed to be better.

As the historian Michael Jago puts it: “Middle-class England was shocked by the persistence of ‘two nations’. Almost one million children were receiving no education at all. There was widespread shame at the failure of the British education system to educate ‘the citizens of tomorrow’.”

Those feelings had been festering. Three years earlier, on 21 December 1941, four religious leaders - the Archbishop of Canterbury, the Archbishop of York, the Archbishop of Westminster, and the Moderator of the Free Church - had sent a letter to The Times. In it, they called for a sense of national renewal. Of education, they said: “Every child, regardless of race or class, should have equal opportunities of education, suitable for the development of his particular capacities.”

This was the same year, 1941, when Winston Churchill appointed his new president of the Board of Education. His name: Richard Austen Butler. They called him Rab.

Churchill viewed working in the education department as a merely managerial role, the principal responsibility being to handle wartime evacuation.

But Butler proved to be anything but managerial.

In the throes of war, new to his post, Butler knew that education was essentially about more than education. It was a pre-eminent building block in national renewal. He immediately introduced provision of break-time milk for 3.5 million children. He doubled the number of daily school lunches to over 700,000. In spite of wartime shortages, this initiative directly led to dramatic improvement in children’s health.

Butler turned his attention next to a bold new education Act.

Churchill’s response was immediate and categorically dismissive. He refused to contemplate new policy while the war continued. This was, he said, no time for party politics.

But Butler pushed on, seeing it not as party politics but as a national mission. And as he laid the education Bill before Parliament, he said: “Let us see that in our time we have achieved something. Let us say that in this time of strife we have ensured the fulfilment of our hopes that a plan for the future world will go through.”

A vision for the future of education

That was 1944, 75 years ago, and it is a reminder, if we needed it, that little matters more than investing in our nation’s future.

It’s a reminder, too, that true leadership rises above adversity, above fragmentation, above accepting the pessimism of inevitability and instead aspires to shape the future rather than being defined by the past.

We need that now. We need some bolder leadership - and far less fear - from those of us involved in all roles in education. Here are three things that might mean in practice.

First, there must be a recognition of what schools and colleges are expected to do. In many communities, they are the last bastion of social cohesion. This means we need a longer-term funding plan for education, one which allows schools to deliver the provision that society expects of them, and properly funds high needs and 16-19 education. ASCL’s analysis, “The True Cost of Education”, puts a figure on how much more schools need - £5.7 billion.

Second, it’s time to sort out accountability. We will always need checks on how well schools and colleges are performing. Ours is a vital public service. But accountability has become a monster that’s driving good people from teaching and leadership, and leaving far too many others anxious and unhappy.

It’s time for proportionate accountability: inspection that helps us to focus on what matters, and performance tables that are only one part of a bigger picture. Other things matter, too - health, happiness, a rounded education, the ability to work with others, the arts - and these need much greater public recognition.

And any accountability system must start from judging us on how we look after the needs of our most vulnerable young people. If we get education right for our most marginalised pupils, we can get it right for everyone.

Finally, it’s time to be more ambitious for our young people. It’s not acceptable that our current exam system writes off more than a third of young people who - after 12 years of being taught by committed teachers and teaching assistants - gain a GCSE grade at English and maths which falls short of a Grade 4 standard pass.

This is a shameful national narrative. We must give our students the dignity of a qualification that shows what they can do, rather than accepting a system that leaves so many young people demoralised and uncertain about their futures. Our Commission of Enquiry into this “Forgotten Third” will report its findings in June.

There’s much more to do, of course. But gloom won’t help us.

Seventy-five years on from the Education Act of 1944, it is time for a new spirit of boldness. It is time to move away from an era obsessed with structural change and arcane accountability mechanisms, and create a vision of an education system for the 21st century.

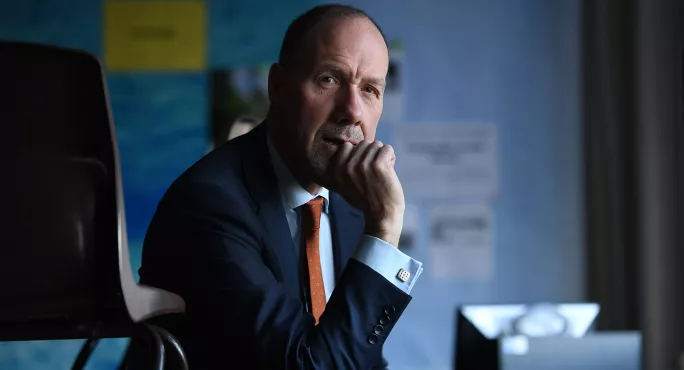

Geoff Barton is general secretary of the Association of School and College Leaders

Keep reading for just £1 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £1 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters