On Monday, I woke up bleary eyed and, as usual, logged in to Twitter first thing to see what education stories were doing the rounds.

My timeline was full of people reacting to a newspaper editorial on universities that said: "The likely bankruptcy of some institutions would be neither surprising nor particularly regretful". This depressing thought was in The Times but it could have appeared almost anywhere.

Last month, for example, David Goodhart of Policy Exchange wrote for The Spectator about his plan to "weed out weaker university courses and create a subset of 'applied universities', undoing the mistake of abolishing polytechnics in 1992".

Mergers: College-university mergers: 'Why wouldn't you?'

Education reform: Why fixing FE shouldn't mean that universities suffer

Background: Youth unemployment could rise by 600,000

Raising the prestige of vocational education

Ostensibly, this new type of institution was designed to raise the prestige of vocational education. But the term "sub" rather gave the game away, as did the fact that Goodhart saw "higher" vocational courses (medicine, engineering and law) remaining the preserve of the older and more prestigious universities.

I responded to the flurry of responses to Monday's editorial by sending out a tweet of my own:

By the time I had got out of the shower, it had gone viral – or at least as viral as any tweet about higher education that includes the word "monopolistic" ever will be.

My tweet hit a nerve because it combined one hoary old chestnut with one (slightly) more original thought. The fact that people who have benefited from higher education do not want others to have the same opportunities resonates because we hear it so often. But I am interested in why they think like this.

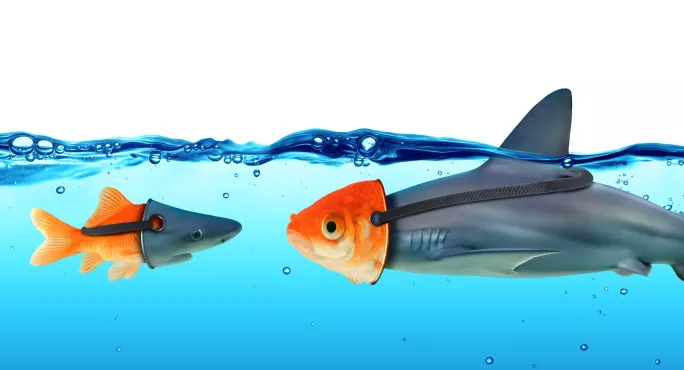

The often overlooked answer is that higher-level skills are worth more if they stay rare. For example, if access to the legal profession were opened up, lawyers wouldn’t be able to charge so much. When people complain that the graduate earnings premium has fallen, it just means that the shortage of higher-level skills is not (quite) as bad as it was before.

But this is not a piece about the value of a traditional degree. It is a piece on how education should fit the aptitude, interests and potential of each individual.

I may not like it when people use the technical university concept as an attack weapon against successful institutions. But if their cure is wrong, their diagnosis is still right: we do need a better technical education offer at levels 4 and 5. Evidence from other countries suggests we have too few people trained to these levels, which lie between A levels and honours degrees. Yet it is not because we are training too many people to levels 6 and 7; it is because too many people cease formal education at just levels 2 or 3.

Let’s get away from sterile debates about whether Anytown University should be renamed Anytown Applied University, Anytown Technical University or even Anytown Polytechnic. Frankly, it is not going to happen. No town or city is clamouring to have their university relabelled and no politician is going to spend political capital removing university status from institutions in marginal constituencies.

Let’s talk instead about the range, quality and number of educational places available. In a recession, we need to open up more educational opportunities – not restrict them. So, for example, instead of worrying about applying new student number controls in higher education, we should be looking to improve funding for further education. We should be considering afresh the student maintenance rules for those not taking traditional degrees. And we should be seeing whether specific support can be put in place to encourage the provision of short courses to keep people off the back of the unemployment queue.

Just before Covid-19 was declared a pandemic, the government published a budget that focused on "levelling up". In a post-Brexit and post-pandemic Britain, that should mean levelling up educational opportunities, not levelling down institutions.

Nick Hillman is the director of the Higher Education Policy Institute