Marking time

It is 20 minutes before the last ever Standard grade modern studies exam is due to finish when S4 students Alex and Harry appear grinning at Eva Georgeson’s classroom door.

The credit paper was “pretty easy”, the students from Edinburgh’s Boroughmuir High School say. Credit papers at Standard grade are usually “really hard”, they confide, but the only thing that made modern studies credit tough was the amount they had to write.

For more than 25 years, young Scots in S4, such as Alex and Harry, have been taking Standard grades, but on Tuesday at 2.45pm, the last ever Standard grade exam - credit accounting and finance - will end. Next year students will sit the new Nationals.

The change is needed, the well-rehearsed argument goes, because the existing qualifications fail to reflect the changes being brought about by Curriculum for Excellence. The Higher will survive, albeit revamped, but Standard grade and the more youthful Intermediate qualifications will disappear.

Dr Gill Stewart, the Scottish Qualifications Authority’s (SQA’s) director of qualifications development, sums it up thus: “The drivers round Curriculum for Excellence were about improving learning and teaching in the classroom.

“If you want to change learning and teaching and you want young people not to be able to just tell you the facts but take their knowledge and understanding of the key concepts and solve problems, you need to change the qualifications.”

So it should come as no surprise that about 95 per cent of the new qualifications involve a coursework element, compared with a third of Standard grades and half of Intermediates.

Not everyone, however, is convinced that the new exams will prove beneficial. The Nationals will lead to cultural impoverishment, says Lindsay Paterson, professor of education policy at the University of Edinburgh, who also claims that the increased emphasis on continuous assessment will reinforce social inequalities because of the help that some more affluent and middle-class children get at home.

Others, such as the independent St George’s School for Girls in Edinburgh, have voted with their feet. The school has opted to run English GCSEs instead of Nationals - a decision driven by a desire to run a two-year academic course before Highers, headteacher Anne Everest explains.

But the changes do have their supporters. Standard grades were out of date, they argue. This year, for example, physics students were still learning about cathode ray tubes and black and white TVs, with no mention of the flat screens that are so much more familiar to them.

Standard grade was also a two-year course and therefore incompatible with CfE, which demands that the broad general education lasts until S3, with certificated courses deferred until S4.

However, whether keen to see the back of them or reluctant to let go, most teachers appear to agree that Standard grades were revolutionary when they were first introduced from 1984.

It is worth taking a brief look back at their fairly extraordinary history, and not least of all the fact that Standard grade reform was credited with bringing about certification for all - not just the top 30 per cent or so who sat the highly academic O-grade qualification, the precursor to Standard grade.

The qualifications were also designed to drive forward changes in learning and teaching, by assessing not just knowledge and understanding but also skills and practical abilities.

In the mid-1980s, Professor Graham Donaldson was the inspector responsible for coordinating the implementation of the Standard grade.

“There was much more active participation of youngsters in the lesson (after Standard grade),” he says. “In science, (students) had to be engaged in practical scientific experimentation and be seen to do it themselves, not just watch a demonstration.”

Ask a teacher the feature of Standard grade they will miss most and they will tell you “the safety net”, which is achieved by students sitting exams at two levels, general and foundation or general and credit.

But over-examination should be avoided, says the SQA’s Dr Stewart. Under the new system, they plan to examine students once at the right level - but a safety net will still exist, she adds.

“If you started out doing National 5 and got the units but then failed the exam, you would slip down to National 4, using the National 5 units,” she says. “Similarly, if you were doing National 4 maths and got one or two of the units but were struggling with algebra, you could move down and do that at National 3 level.”

For students at foundation level, an external exam is inappropriate, Dr Stewart believes. Internal assessment will suit these students better and allow them to build their confidence, she says.

The three levels were introduced with the best of intentions, says Sally Brown, professor emeritus of education at the University of Stirling and convener of the Royal Society of Edinburgh’s Education Committee. It was hoped that problems of equity would be fixed by ensuring that the lowest achievers received some sort of certification - but ultimately they were used by employers and higher education to “sort the peacocks from the sheep from the goats more rapidly”, she says.

“A foundation certificate was interpreted negatively by many as “bottom of the pile”, rather than as the “evidence of valuable learning” that it should have been, she adds.

However, the equivalent at Nationals - National 3 - will have a lower status still because it will be internally assessed by teachers and therefore lack credibility, Professor Paterson says.

“Before Standard grade, it had been assumed that only a minority would get access to the best knowledge and the most challenging ideas but that was something Standard grade refused to accept,” he argues.

“The new Nationals fail to come anywhere near the democratic ambitions that Standard grade had. They are not based on any curricular philosophy at all, there is no linking to our inherited culture and no sense that the school curriculum or the exams are giving teenagers access to the foothills of culture. The whole thing is relevant to the world of work. There has been an enormous cultural impoverishment since Standard grade.”

Teachers will continue to teach in the Standard grade tradition but they do this despite changes to the system, not because of them, Professor Paterson argues.

Professor Brown is also uncomfortable with the new curriculum and exams but for a different reason - they have never been effectively evaluated, she says.

She managed the research programme launched in 1980 that led to the introduction of Standard grade. There were more than 25 research projects over a six-year period and pound;1 million invested - very significant funding at that time.

“Sadly, there has been no such independent research or evaluation programme associated with Curriculum for Excellence,” she says.

Back at Boroughmuir High, Alex and Harry are divided. More continuous assessment would not suit Harry, who prefers doing an end-of-year exam than having things “spread out over a period of time”. Alex, however, can see the wisdom in placing less emphasis on external examination. “I’m not really stressing about my exams, but everybody else is,” he says.

However, their headteacher, David Dempster, believes there will be more assessment, not less, under CfE, especially at National 5, with three internal assessments per subject, an “added value unit” and an external exam - all in the course of just one year.

He remembers the introduction of Standard grade fondly - in particular the way it was resourced, with a lot of training available, including teachers being taken out of school to write course materials and assessments and shiny new equipment arriving at schools.

There is a need to future-proof the curriculum with the broad experiences and outcomes of CfE, he admits, but even with the recently produced additional support materials, teachers still have a mountain to climb, he believes.

But the introduction of Standard grade was also fraught, Professor Donaldson recalls. The unrest in the teaching profession in the 1980s had as much to do with the work associated with Standard grade as with pay, he says.

“Almost every major change, if it is worthwhile, has produced that initial period of uncertainty and difficulty,” he adds.

Key statistics

55,793 - The number of students sitting at least one Standard grade this year.

338 - The number of schools with students sitting Standard grades.

1,156,865 - The number of candidates who have sat Standard grades since 1995, when the Scottish Qualifications Authority records began.

68,705 - The number of candidates who sat Standard grade in 2008, when it was at its most popular.

Source: SQA

Background to the standard grade

Standard grade came into being following the Munn and Dunning reports of 1977.

The Munn committee reported on the curriculum and the Dunning committee on assessment.

After a long period of consultation and development, Standard grade was introduced from 1984. Its implementation was delayed in part because of poor industrial relations. The 1980s was a decade of discontent among teachers in Scotland with a protracted period of industrial action from 1984 to 1986. Also, policies had been put on hold in 1979 when the Conservatives came to power to allow the new government to decide where it stood.

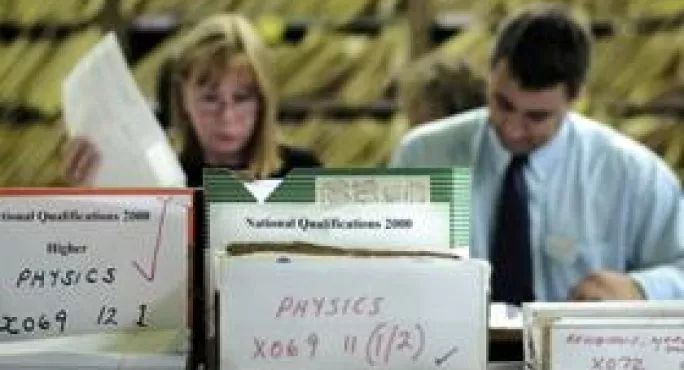

Photo credit: Getty

Original headline: Stop what you are doing, the Standard grade is over

Keep reading for just £1 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £1 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters