Meet the academy boss who wants to scrap performance-related pay

Share

Meet the academy boss who wants to scrap performance-related pay

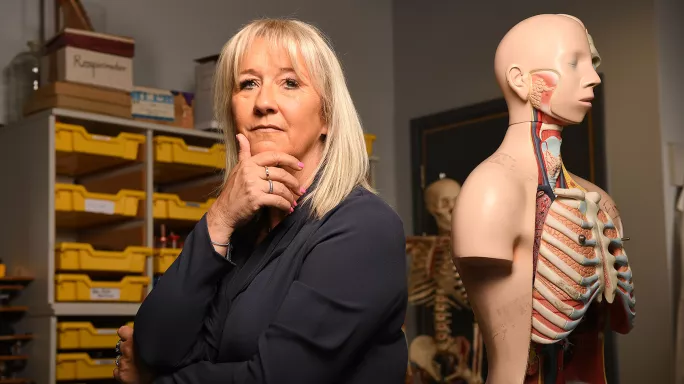

Jane Millward wants to put people first when she takes the reins at one of England’s most prominent multi-academy trusts in September.

She is a former Ofsted inspector who was once at ground zero in one of the most controversial episodes in England’s recent educational history, which led to cabinet splits and national debate about what it means to be British.

Now, whether it is the mental health of staff and pupils or reforming how her teachers are paid, there is a very human dimension to the priorities of E-Act’s next chief executive.

“If our people are the very, very best people that we can get, and they stay with us, and they develop with us, and they see that there are opportunities to develop and be promoted within the organisation, then everything else, I believe, will follow,” she says.

Academies: ‘Making a difference’

Millward joined E-Act from Ofsted in 2016, becoming one of its regional directors of education. It was a career change that she acknowledges came a surprise to some of her friends and colleagues.

“I think at the time E-Act didn’t have a great reputation, but they also acknowledged that MATs need good people working for them, so they said, ‘Great, go and make a difference,’” she recalls.

Profile: The man who thinks grammar schools are the answer

No Outsiders: ‘I remember being an outsider’ - teacher at centre of LGBT row

Academies: Meet the man at the top of the academies tree

The academy trust had become a byword for all that could go wrong in the early days of mass academisation: over-ambitious expansion, soaring executive pay and poor academic results.

Back in 2011, it was talking about establishing a “super chain” of 250 schools, but two years later a government investigation raised concerns about “extravagant” expenses, “prestige” venues and first-class travel.

Its director-general, Sir Bruce Liddington, who earned almost £300,000 in wages and pension contributions in 2010-11, resigned after E-Act became the first multi-academy trust to receive a financial notice to improve.

But under subsequent chief executive David Moran, who Millward is succeeding, the trust was stabilising. As one newspaper headline in 2015 put it, “E-Act academy chain abandons plans for world domination”.

Back then, it was stripped of 10 of its schools, but over the past three years it has begun to grow again, at a modest pace, and in 2018 its primaries were above the national average for writing and maths.

But while the E-Act of today is very far from the E-Act of five years ago, it still has real work to do.

Its secondary schools last year had a below average Progress 8 score of -0.17, and earlier this year the Department for Education threatened to terminate the funding agreements for two of its schools.

But the appointment of Millward, an internal candidate, as CEO is a sign of confidence within E-Act that it is going in the right direction.

‘I would rather work where children really need us’

Millward describes her own education in Cheshire as “very standard”, although it came during an earlier period of upheaval in the state school system.

Her secondary school was a girls’ grammar when she joined it, but had become a mixed-sex comprehensive by the time she left.

The effect of the change to non-selection and the admission of boys - “which was really quite exciting” - was apparent to the teenage Millward.

“The teachers really struggled, because they had obviously always taught nice girls who wanted to learn, to then getting the comprehensive sector in, and boys with their own challenges,” she says.

“Teachers left in droves because it just wasn’t for them, so it was quite unsettling.”

Even then, she knew she wanted to be a teacher and “make a difference”, and working in grammar or private schools held no appeal.

“I never felt I wanted to go into a privileged sector because I would rather work where children really need us. I think that’s very much what E-Act believes,” she says.

In her career, Millward has jumped between working inside schools - as a primary teacher, head and now academy chain leader - and working with them from the outside - as a literacy consultant in the Labour government’s national strategies, at a local authority and at Ofsted.

Her time working on school improvement at Cheshire County Council “was my moment to realise I want to impact much wider, and rather than just impact on just one school, have a broad perspective of a range of schools and a range of pupils”.

It was also at this point that she realised that the role of councils in education was diminishing, so she decided to go to Ofsted.

“Becoming an HMI was kind of my defining moment of what I am and what I have become. My experience being an HMI was fantastic, and I do think it made me into the educationalist I am now,” she says.

Hostility and Trojan Horse

It was when she became a senior HMI in the West Midlands that she became involved in the response to the Trojan Horse affair, which centred on an alleged plot by some Muslim groups to take over some secular state schools in Birmingham by infiltrating their governing bodies.

It was a controversy that played out on the front pages of national newspapers, led to a bitter cabinet feud between Michael Gove and Theresa May, and fed into a national debate about Islam and British values.

Ofsted was a central player, plunging schools from “outstanding” to “inadequate”, despite often superb academic results.

Millward inspected “quite a few” of these schools herself, and became the monitoring inspector for some after they went into special measures.

“I saw first-hand the impact on children who were getting a narrow curriculum and were being given some opportunities and denied some other opportunities that they were entitled to,” she recalls.

Five years on, it is a period about which she still picks her words carefully. “It was really challenging,” she says, adding that “there was hostility” at times.

“There were aspects within the school that, as an inspector, we did not believe were appropriate, and we wanted to ensure that children had every opportunity available to them.

“We also got external influences from the community that they were very happy with the school and how it was run previous to our intervention.”

In recent months, Birmingham has again been at the subject of headlines about the role of faith schools in modern Britain, with some Muslims protesting outside primary schools about LGBT content in lessons.

Parkfield Community School, which has been at the centre of this controversy, is not far from some E-Act primaries. But Millward says that dialogue with their parents about how the schools fulfil their obligations under the Equalities Act, and how they help pupils understand about different types of families, has been successful.

‘I decided to make the move’

It was her role at Ofsted that led Millward to make the decisive career change that would eventually see her become chief executive at E-Act.

She was the monitoring inspector for one of the trust’s academies in Birmingham, Nechells Primary, which saw her work closely with E-Act CEO David Moran.

“I think David and I, it’s fair to say, were quite aligned with our philosophy and what we wanted to achieve and our ideologies around education, so I got to know E-Act a lot better from that and decided to make the move to join E-Act.”

Since then, her rise has been meteoric, from regional education director in the Midlands to national director of education, and now deputy CEO.

It therefore came as little surprise when she was named Moran’s replacement in March.

‘No child will be permanently excluded unless I say so’

In recent months, few education issues have had as high a profile as exclusions, and over the past 12 months Millward has taken an approach she has not heard of in other large MATs.

No child can be permanently excluded from an E-Act school without her personal approval, although the legal responsibility remains with headteachers.

“We will permanently exclude as an absolute last resort, and because I think that then makes a child vulnerable if they have been excluded from school, every permanent exclusion has to come to me, and no child will be permanently excluded unless I say so.

“I have to understand the reasons and I have to see the evidence, as it has to be the last resort.”

There have already been times when has demanded further evidence, and she believes her involvement has reduced the number of permanent exclusions. It is a role she will continue to play as CEO.

On a related issue, off-rolling, E-Act found itself in the news for the wrong reasons when Ofsted said it suspected one of its schools, Shenley Academy in Birmingham, of the practice.

Asked about this, Millward says: “We are very clear that it is completely unacceptable, and something that I won’t tolerate and E-Act won’t. I am absolutely determined that it cannot happen in any academy, and we did take action against it.”

Scrapping performance-related pay

Millward’s priorities as CEO centre on people. For her, if E-Act has the best people it can get and does right by them, then “everything else, I believe, will follow”.

Her “big piece of work” is a project to scrap performance-related pay at E-Act, something that she thinks will make a “massive difference”.

“If we want to have openness and honesty and transparency, and have teachers who really want to improve, then we need to take pay away from that discussion.

“I don’t believe that a Year 8 teacher, if they are struggling with teaching on a Wednesday afternoon, is going to go to their head of their department and say, ‘Can you help me with this?’ because their pay will be affected by it.”

She is almost evangelical about the proposal, which E-Act is working with unions to deliver.

“I just think it’s going to give us the freedom to actually be creative, to be innovative, to share our best practice, and actually not be afraid to make mistakes.

“We learn by our mistakes, don’t we? And if it’s OK to make a mistake, we can improve.”

‘Children who don’t know if they want to stay alive’

One area where E-Act has developed a reputation is mental health, and in 2017 it talked about plans to train all its staff as mental health first-aiders.

It was an initiative that Millward oversaw, and she recalls crying last year when she listened to a Year 9 girl at one E-Act school outline her own experiences.

“She talked about being isolated and she talked about not having any friends and she talked about self-harming, and she talked about when she tried to kill herself. And then she said, ‘Because of my teachers here, I’m now better.’

“Did I have any idea, if I’m honest, of how many children self-harm? I didn’t, and I don’t think we have any idea, as a nation, how much this is impacting on children, and we have to support them.

“I can sit here and talk about it being really important to get English and maths, and absolutely it is really important because that’s their passport out, but we have got children who don’t know if they want to stay alive.”

Now, she wants to extend the help available for adults at the trust.

“Looking at our work with people, I want to train adults in mental health for adults,” she says.

“Any line manager, I believe, should be a qualified mental health first-aider, so that when they meet with people who they manage they understand issues that our staff may be facing and can put in support for them, so we look after our staff better and give them the support they need.”

With mental health, pay and teacher recruitment and retention key challenges facing England’s school system, E-Act will be hoping that Millward’s people-centred approach will help it continue its upward trajectory.

CV - Jane Millward

Education: St Dominics, Stoke on Trent; Congleton High School; Manchester University (BA Geography and Education; Westminster College, Oxford (PGCE)

Employment:

1990-1998: Class teacher/subject leader (Upton Priory Junior School, Macclesfield; Alderley Edge Primary, Alderley Edge; Quinta Primary, Congleton)

1998-2000: Deputy headteacher, Quinta Primary

2000-2002: National strategies, literacy consultant

2002-2015: Headteacher, Wimboldsley Primary, Middlewich, Cheshire

2002-2010: Cheshire County Council: Data and monitoring officer and senior school improvement officer

2010-2013: Ofsted, HMI

2013-2015: Ofsted, senior HMI

2015-2016: Ofsted, senior operational lead

Sept 2016-Dec 2016: E-Act, regional education director

Dec 2016-Oct 2017: E-Act, national director of education

Oct 2017-present: E-Act, deputy chief executive

From Sept 2019: E-Act, chief executive