Scotland has one. Wales and Northern Ireland have them. Even the city of Manchester now has one. But England still has no strategy for English for speakers of other languages (Esol).

Calls for a national strategy have been growing louder since an Esol manifesto was drawn up by practitioners in 2012. The On Speaking Terms report by the Demos thinktank in 2014 increased the level of interest in the subject.

In January 2016, then prime minister David Cameron announced a £20 million Esol programme for Muslim women from isolated communities to “bring Britain together and build the stronger society that is within reach”.

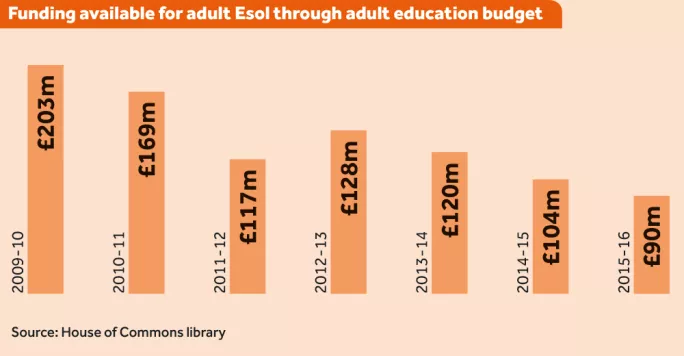

But, with the announcement coming shortly after £45 million of cuts to Esol programmes for the unemployed, affecting 16,000 learners across 47 colleges, the move did little to suggest that Esol was being taken seriously in the corridors of power. The drop in funding levels since 2009 appears to reflect this (see graph, below).

Amid the apparent absence of strategic thinking in Whitehall, the Esol community took matters into its own hands. In October 2016, the National Association for Teaching English and other Community Languages to Adults (Natecla) launched its own draft strategy, calling for a radical overhaul of how provision is taught, coordinated and funded. This included calls for Esol to be free for newly arrived asylum seekers and people with low literacy in their first language.

The move attracted significant attention. Sue Pember, a former senior civil servant and director of policy and external relations at adult and community learning provider Holex, described it as a “gap in government policy that the sector has started to fill”.

Next week marks one year since the launch of the report. A meeting at the House of Commons on Wednesday will reflect on what progress has been made.

So is England any closer to its first national Esol strategy? A follow-up report, shared with Tes, suggests there has been some progress.

Dame Louise Casey’s government-commissioned review into integration, published in December, argued that a shared language was “fundamental to integrated societies”, and that the government should be making “sufficient funding available for community-based English language classes, and through the adult skills budget for local authorities to prioritise English language learning where there is a need”.

In August, the All Party Parliamentary Group on Social Integration called for a “comprehensive strategy to promote English language learning”. But with the first moves to devolve skills funding now less than a year away - in theory at least, given difficulties across several English regions - there has been little overt appetite from central government to produce a national strategy.

“We still need better coordination at a national and local level,” says Natecla co-chair Jenny Roden, “especially with skills devolution on the way. In order to ensure there’s good coordination and a good level of education for everyone, whatever their needs may be, we need a national strategy. We’re not saying ‘give us lots of money’, but ‘use the money you’ve got effectively’.”

A Department for Education spokesperson says that Esol is part of its “wider efforts to improve adult literacy in England. This is why we provide funding to support adults to improve their levels of English.”