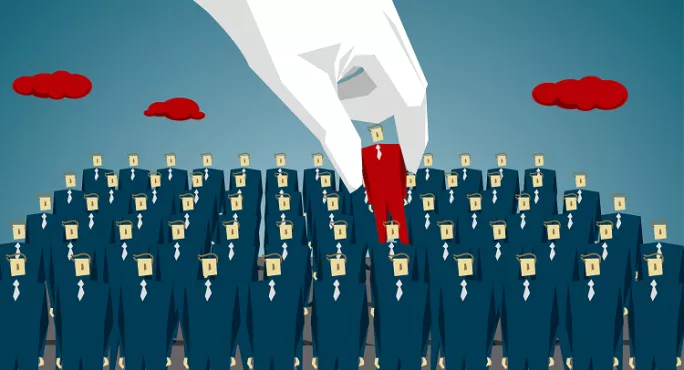

Ofsted purges 40% of inspectors

Ofsted is ditching 40 per cent of its contracted inspectors after assessing them as not good enough to judge schools reliably, TES can reveal.

The watchdog’s purge of 1,200 inspectors comes as part of its plan to improve quality and consistency, which will also mean the remaining inspectors being graded after every school visit.

Sir Robin Bosher, Ofsted’s director of quality and training, told TES: “Our absolute aim is to have the highest-quality inspectors we can. I am committed to making sure that my colleagues in headship can be assured they have a good inspector walking up the path. I’m determined that will happen.”

He said the inspectorate had reduced its headcount through a robust assessment process. It meant that approximately 2,800 additional inspectors who had expressed an interest in becoming in-house staff had been whittled down to just 1,600.

Sir Robin revealed that one of the key reasons for rejecting so many was their lack of skill in writing reports, an area that has been a source of serious -concern for many schools.

Headteachers have given the news a guarded welcome. But there is frustration about it not happening sooner.

Russell Hobby, general secretary of the NAHT headteachers’ union, said that Ofsted deserved praise for its actions. But he added: “You look back and say, for the last few years we’ve been inspected by a group where 40 per cent weren’t up to the job.”

From September, all Ofsted inspectors will be employed directly by the watchdog. After every school inspection they will be graded by a lead inspector, who will report back to Her Majesty’s inspectors (HMIs) and Ofsted’s regional directors.

Sir Robin said he was “confident” that the new approach would allay headteachers’ fears over quality and consistency, but added that no system would be perfect and he could not rule out problems in the future.

“We’re dealing with human beings,” he said. “We’re not making telephones, we’re delivering inspection. It’s a human process, and because of that there’s room for things not to be right.”

However, he was quick to point out that the reduction in inspector numbers did “not equate” to Ofsted being substandard up to this point, and said he was not anticipating any complaints from schools. He added: “It should be remembered that not everyone who is currently an additional inspector and didn’t become an Ofsted inspector was -necessarily rejected - some decided to stop inspecting.”

Ofsted had been using about 3,000 inspectors employed by outside contractors, about 200 of whom decided not to apply to work in-house for the watchdog. Chief inspector Sir Michael Wilshaw announced last year that Ofsted would no longer use such “additional inspectors”.

Janis Burdin, headteacher of Moss Side Primary (see below), an outstanding school in Lancashire, was not convinced by Sir Robin’s reassurances. “If 40 per cent have been viewed as not good enough to continue, what does that say for all those who have recently had inspections?” she asked.

Geoff Barton, headteacher at King Edward VI School in Suffolk, last week published a widely read blog on the TES website, which quoted other school leaders and even an HMI about their disillusionment and despair over Ofsted. He said it was “good that it was trying to put its house in order”.

“For many of us, there’s a lot the organisation needs to do in order to restore its tarnished reputation,” Mr Barton said. “I am reassured that they are purging so many inspectors, but -ultimately it’s the quality of inspection rather than the quantity of inspectors that matters.”

He added: “School leaders want to be reassured that this smaller team will be consistent in their judgements and committed to helping rather than humiliating schools.”

Sir Robin said that an “initial sift” of additional inspectors took out about 500 who lacked the relevant qualifications or leadership experience, or did not possess qualified teacher status.

The watchdog hopes to have a working body of between 1,800 and 2,000 inspectors, and is looking to recruit about 300 more to fill gaps in specialist provision. According to Sir Robin, more than 2,000 applications are waiting to be assessed, as the role is now popular among -leadership teams as part of their professional development.

Mr Hobby said: “If Sir Michael Wilshaw had done this from the start, we would have avoided everything that has followed. If people could say it’s tough but fair then fine, but it was tough and unfair and tackling that should have been a priority.”

The headteacher’s view:

Janis Burdin has been head of Moss Side Primary School in Lancashire since 1982. In that time she has experienced five inspections, and says their quality has dropped in recent years - the latest one being led by someone who had only worked in tertiary colleges.

“They have never, ever revealed anything that we weren’t already aware of before and the standard of different inspection teams varied markedly,” Ms Burdin says.

She adds: “They have also become very data-led, so whatever great work you’re doing in class, whatever curriculum you’re offering, if the data isn’t up to scratch they can’t see further than that.”

The move towards a more centralised system is also having an adverse effect, Ms Burdin argues. “It used to be done along with the local authority, who knew the school well and would oversee and support the school where necessary. It was a lot less threatening and more productive. They had the effect of supporting schools without terrorising them.”

Keep reading for just £1 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £1 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters