This year’s Pisa results mean that Scotland can now say its 15-year-olds are above average for reading - although they remain average at science and maths, according to figures published today by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD).

This marks an improvement on Scotland’s results in the 2015 Programme for International Student Assessment - which measures 15-year-olds’ ability in reading, mathematics and science every three years - when Scotland was deemed average for all three areas.

However, the mean score achieved by Scottish pupils in 2018 rose only for reading - it fell for maths and science when compared with 2015, although the government insisted that those falls were not statistically significant.

Pisa 2015: ‘Five years left’ to save CfE after Pisa plunge

Background: The Pisa rankings and Scotland: what you need to know

Related: No change in direction for education, vows Swinney

The critics: ‘Ignore Pisa entirely,’ argues top academic

Short read: Scotland’s poor education image blamed on ‘wild misreading’ of research

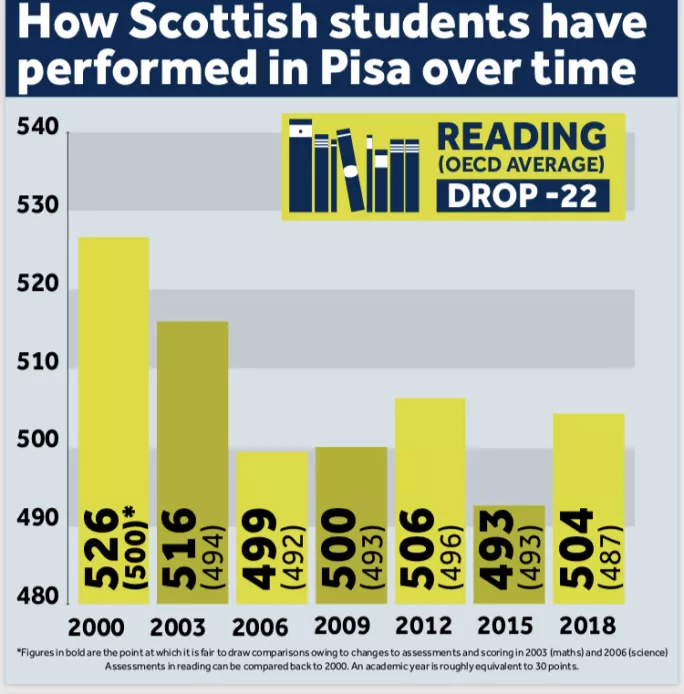

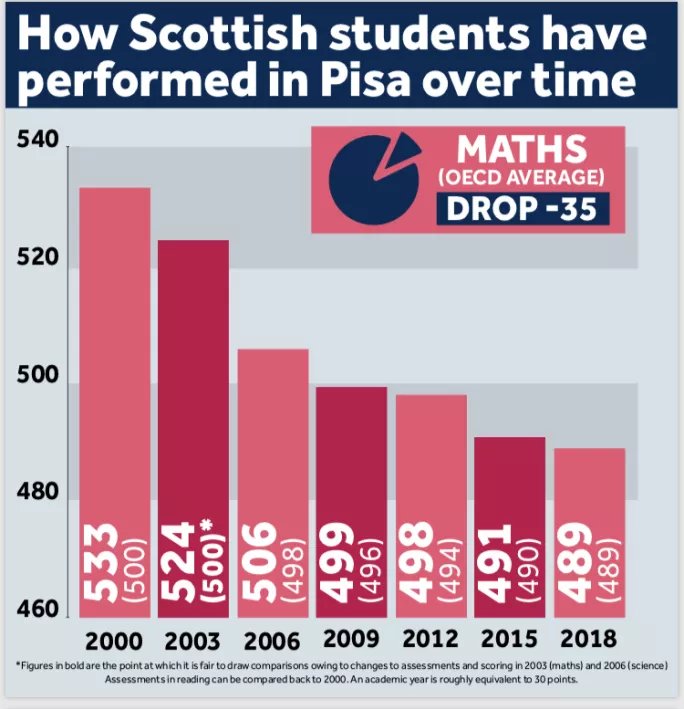

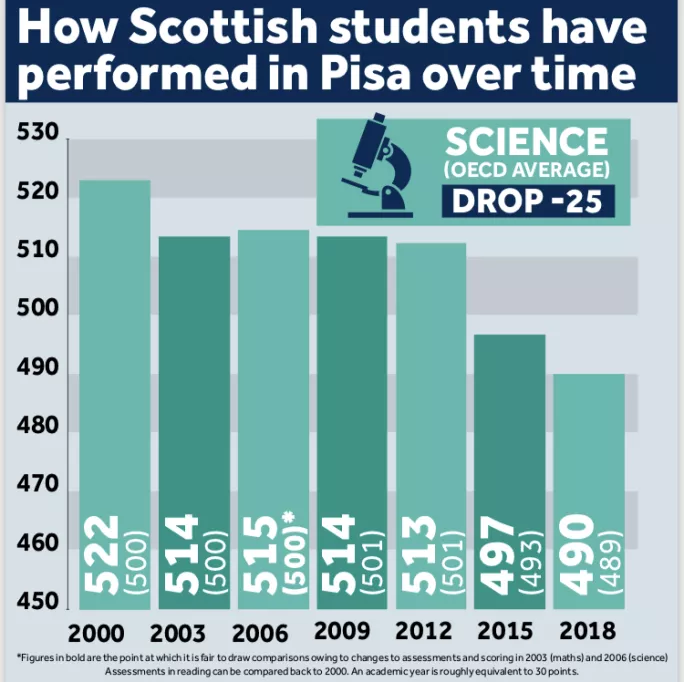

Scotland achieved a mean score of: 504 for reading, up from 493 in 2015; 489 for maths, down from 491 in 2015; and 490 for science, down from 497 in 2015.

Scottish pupils’ performance for reading has dropped by 22 points since 2000; pupils’ performance in maths has dropped by 35 points since 2003; and pupils’ performance in science has dropped by 25 points since 2006.

Comparator years vary owing to changes in the way the assessments were run.

English pupils achieved a higher mean score than Scottish pupils in all three areas, with pupils in Northern Ireland doing better in maths and science but not in reading.

Wales - which is in the process of introducing a new curriculum modelled on Scotland’s Curriculum for Excellence - lagged behind the other three home nations in reading, maths and science.

Pisa claims to be “the world’s most comprehensive and reliable indicator of students’ capabilities” and “the world’s premier yardstick for evaluating the quality, equity and efficiency of school systems”.

However, others say that the two-hour test - sat by 600,000 students in 79 countries and economies last year - does not measure what matters.

In 2016, in the wake of Scotland’s disappointing Pisa results, the University of Edinburgh’s Professor Lindsay Paterson said that they marked the worst news for Scottish education in his 30-year career. And education secretary John Swinney, who had been in post for just seven months, said that “radical reform” was needed.

Yesterday, before the latest results were published, academics and commentators were already warning it was important to “keep Pisa in perspective” and not to indulge in “poorly informed panic”.

Mr Swinney recently promised Scotland’s directors of education that there would be no change of direction for Scottish education. He said “the classic weakness of politicians” was that after a while, when things got “a wee bit familiar”, they decided to “go off and do something else”.

In 2018, the four areas of China that participated in the study - Beijing, Shanghai, Jiangsu and Zhejiang - outperformed by a large margin their peers from all the other 78 participating education systems in maths and science.

Moreover, the 10 per cent most disadvantaged students in these four jurisdictions were also found to have better reading skills than those of the average student in OECD countries, as well as skills similar to the 10 per cent most advantaged students in some of these countries.

Most OECD countries recorded virtually no improvement in the performance of their students since Pisa was first conducted in 2000.