Pupils have been “trapped” by low expectations and teachers overburdened by unnecessary workload because of a fad to crudely tailor teaching to children’s individual wants, a former government adviser has warned.

Tim Oates, who led the last national curriculum review, said teachers in England had been “very badly” let down over the past 20 years because of the “problematic” approach to ”personalised learning” that has been pushed in schools.

In a blog published on the Council of British International Schools’ website, Mr Oates takes aim at personalised or “individualised” learning - an educational approach that he says entered England’s classrooms in the 1990s and revolves around prioritising the individual wants and needs of children.

In the blog, Mr Oates, Cambridge Assessment research director, compares this approach to “quasi-scientific notions” such as “learning styles” and “skills not knowledge”, which he says have “cost systems - and individual children - dearly”.

“The push to particular forms of ‘personalised learning’ has led to a tangible rise in pressure on teachers: differentiated lesson plans; managing the progress of children ‘all moving at a different pace’; individualised tracking systems with ‘flags’ and ‘alerts’ when ‘predicted grades’ are not being attained month by month.”

‘Unmanageable expectations’

Speaking to Tes, he said that England’s approach to personalised learning had been “really problematic” and “given rise to a completely unrealistic and unmanageable set of expectations on teachers”.

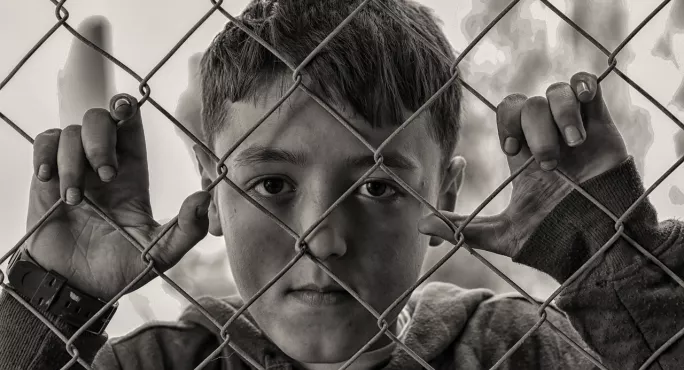

He said that in some schools children had ended up “trapped” by their predicted grades, with teachers viewing poor results as acceptable because they were in line with the pupil’s prediction.

“They’ve got green boxes against very, very low grades, but that’s because they’ve entered from poor performing primaries with very poor key stage 2 results,” he said.

Mr Oates also said some primary schools pandered too much to pupils, pointing to research by Peter Blatchford, which found children could “opt-out” of learning activities and be supervised by a teaching assistant instead.

This resulted in them losing out badly on curriculum content, Mr Oates said.

He told Tes: “There should be no self-fulfilling prophecies in education, where you use say data and tracking systems to say, ‘OK, this is what we expect from this child. This is what they’re going to get because we’ve given them a limited diet based on what we thought there were going to ge’.’”

Mr Oates said that his claims were backed up by the Programme for International Student Assessment (Pisa) league tables, which showed there was “no change” in England “during the time we would have expected to see a pay-off from personalised learning”.

However, Mr Oates insisted he was not arguing “that education should not respond to the needs of the individual”.

“I’m absolutely in favour of individualised learning, but only done in ways that make sense,” he said.

In his blog, Mr Oates says that high-performing systems like Japan and China, which ostensibly appear “unpersonalised”, actually have a much better system of individualised learning.

“[In Japan] teachers see it is as their responsibility that each and every child should understand every idea, and those struggling or building up misconceptions should rapidly be identified and receive immediate support,” he writes.

“There, this means all children following the same overall programme, not different ones.

“On the outside, it all looks unpersonalised, but beneath the surface, the attainment of each and every child carefully is attended to.”

Mr Oates is due to deliver a keynote speech on personalised learning at the COBIS annual conference later this month.