Parents’ requests for their summer-born children to delay their start to school have plateaued since last year after nearly doubling between 2016 and 2017, according to figures published today.

The Department for Education surveyed 94 local authorities about their admission policies for summer-born children and the number of requests to delay their entry to school last year. Of those, 62 had completed the survey in 2017.

News: Huge increase in summer-born pupils delaying school

Related: Summer-born children should have test scores adjusted

Quick-read: Attainment gap for summer-born pupils ‘persists at age 11’

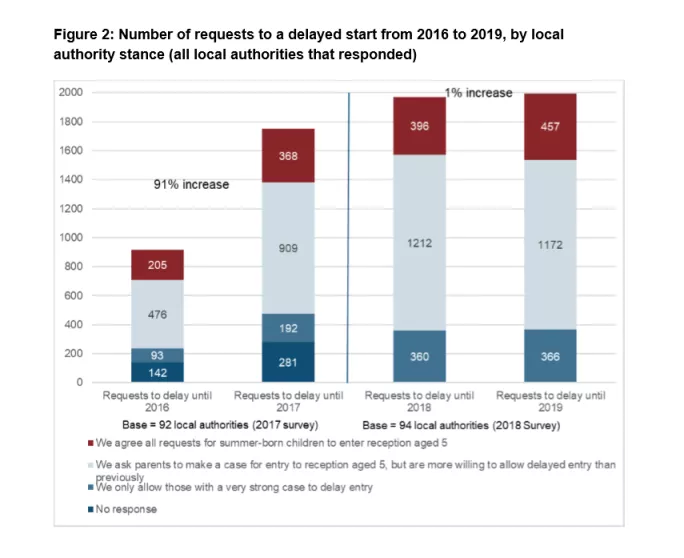

There had been a 91 per cent increase in requests for delayed entry to Reception between 2016 and 2017, from 916 to 1,750.

And this was followed by a 12.5 per cent rise the following year, to 1,968.

But there has been a 1 per cent decrease in the number of requests between 2018 and 2019, to 1,995.

The DfE’s report on the data, published today, says the number of requests “appear to have plateaued for entry in 2019” but “it is too early to say that this is a trend”.

The largest increase in the number of requests to delay entry was seen in local authorities with a more lenient admissions policy that agreed “all requests” for a later start.

These authorities saw a 15 per cent year-on-year increase, from 396 to 457 requests.

However, authorities that only allowed later entry if parents made a very strong case for it saw an increase of just 1 per cent.

Local authorities must provide a school place for children in the September following their 4th birthday, which is when children usually start school.

However, parents of children born between 1 April and 31 August can ask to delay their child’s entry to school by a full academic year after they are given a place, so that they are admitted into Reception the following year, rather than Year 1.

Most local authorities granted parents’ requests. In 2019, 88 per cent of authorities granted these requests, compared with 80 per cent in 2016.

In the most recent survey, most authorities - 85 per cent - also encouraged parents to speak to schools about their concerns over summer-born children starting school too early. The study found that parents can underestimate the level of support for younger children in Reception classes.

One respondent said: “Parents do not realise that schools can often support the additional needs that their child has, in which case, delayed entry may not be required.”

Another said they advised parents to speak to their child’s school so that they are aware of how provision is “specifically tailored to meet the needs of the youngest pupils”.

“Many parents request a delayed entry as they feel this is the only option. When talking to schools they understand more how the school can meet their child’s needs and the benefits of being with their academic peer group,” the respondent added.

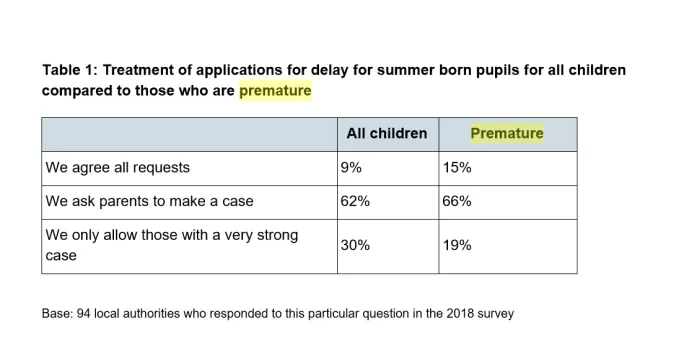

The survey found local authorities were more likely to grant requests for delayed entry for children who were born prematurely. In total, 15 per cent agreed requests for premature children, compared with 9 per cent for all children.