The Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development has published a new report: Measuring Innovation in Education 2019. The focus is firmly on classroom practice: in his foreword, Andreas Schleicher makes clear that a lot of top-down policy change does not amount to innovation in teaching and learning. He says that: “some countries have invested in major curriculum reforms, but saw little innovation in the classroom”. In England, to be sure, we have not lacked policy change, whether in school organisation, national curriculum revision or examination reform.

Classroom practice has, of course, to take these external factors into account, and innovation, whether pedagogical or technological, takes place within constraints. These fetters are, to be fair, hardly hidden and can scarcely be taken for granted in ‘delivering’ the secondary curriculum and preparing students for high-stakes tests.

But there are some external factors that are so embedded that they go largely unquestioned in the quotidian flow of events and exigencies, and are most definitely not on the government radar. Unlike exam change, they are not cheap policy levers. They are foundational features the removal of which would entail considerable cost and upheaval. Each of them made sense when they were laid down: but they no longer seem in sync with the modern world and its needs. Together they set the temporal framework for schooling.

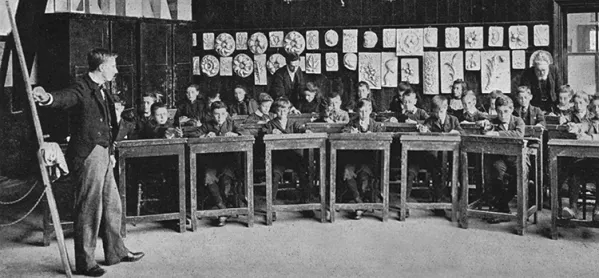

The English school year, with its three terms of unequal length and long summer break, made sense in the late 19th century when elementary education became compulsory, and a compromise had to be made between the needs of rural and urban populations. This wasn’t always the case: in earlier centuries Eton’s school year customarily consisted of two halves, with two three-week breaks at Christmas and in summer. (They still call terms ‘halves’, even though there are three of them.) The well-attested ‘summer learning loss’ reflects the fact that school calendars do not fit any model of mastery learning.

The school day, being several hours shorter than the typical working day, made sense when the Leave It to Beaver’s June Cleaver stood for the archetypical stay-at-home mum. It makes much less sense in an economy where both parents work, and when children are increasingly discouraged from travelling alone. Schools have worked to offer care before and after school, and in the USA the National Center on Time and Learning lobbies for ‘expanded learning time’.

The institutional break between primary and secondary is not based on a model of child development. In the nineteenth century, elementary and secondary education ran in parallel rather than in series. Privileged children went to secondary schools, but when the state imposed compulsory schooling on the working class, it covered only the elementary phase. Plans in London to develop a ‘higher elementary’ stage were strangled at birth for political reasons. Instead, scholarship ladders were manoeuvred into place to allow a few poorer children access to secondary schools, but on middle-class terms.

The OECD report points to the innovations that are possible within such anachronistic constraints. Teachers work within them and do their best to deliver meaningful modern outcomes, and the results are pretty impressive. But without any strategic review of the temporal, physical and institutional structures within which they work, it is a bit like the owners of the Titanic seeking ways of improving the customer experience without considering either the hull’s design or the route taken. There is a limited number of ways of rearranging the deckchairs.

Kevin Stannard is director of innovation and learning at the Girls’ Day School Trust. He tweets @KevinStannard1