It’s the masks I am worried about.

Sure, the idea now of standing in front of a group of students sniffling with colds and flu - or worse - in November is something that I am, well...conflicted about.

But I will do what most teachers plan to do: compartmentalise the perceived threat, focus on the lesson, drill down into the task being taught and avoid talking about the herd of elephants in the (class)room.

Perhaps when a student, unburdened by intimations of mortality, explodes in a seasonal outburst of germs, releasing a fine mist of spray of teenage droplets to settle, invisibly, in an innocuous (or not) film on desk, chair and hair, I’ll feel differently.

“Sir, can I get a tissue?” That otherwise innocent request could, in the future, be invested with a mixture of emotions.

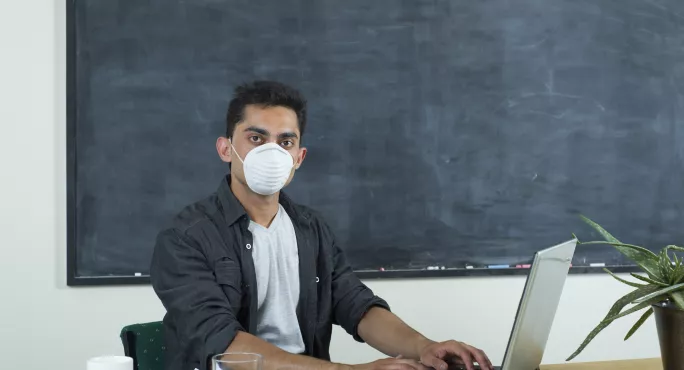

So, perhaps I should wear a mask. And I should insist that everyone in my classes also wears a mask. That would mitigate such thoughts, shouldn’t it?

It would certainly lessen the intensity of each Pinter pause that now, inevitably, follows every cough.

Losing a human connection

Yet, when I look at those rows of students in China and South Korea, their faces partially anonymised by their facial coverings, all uniform, all antiseptic in intent and appearance, something in me as a teacher recoils from it.

A precious link of humanity is broken, even though a stronger one - the preservation of health, and life - is underscored by their ubiquity.

And I know the cultural sensitivities involved in stating such reservations, although I expect that the medium-term normality for a growing number of those of us in the secular West will soon have to segregate our conflicted thoughts about this facial self-censorship.

Even so, the masks still worry me.

They worry me because so much of teaching relies on conveying our thoughts through our gestures, and this is reciprocated by our students.

We know that young children learn from imitation, and they read us, and how we react, as closely as any storybook, possibly because each subtle alteration, each muscular emphasis, alters the stress of how we appear.

Our students are quickly able to distinguish between an insincere Pan-Am smile and a genuine Duchenne smile; our expressions have a grammar of their own, their syntax and punctuation being sophisticated forms of communication, now about to be redacted.

Muting our emotions

Those passing moments of recognition, or understanding, of disagreement, and respect...the whole gamut of that wonderful human vocabulary, will be muted.

Perhaps we will refocus, teaching our eyes to say even more than they do already, moving our hands more extravagantly, learning to convey as much as we used to in that smaller, exposed space.

Perhaps we will rely more on the written word to fill in the gaps that we left unarticulated in the lesson when discussions faltered, or meanings were misunderstood.

Or perhaps it will be considered too much of a sacrifice after all, and that the innate humanness of what we say, and how we say it, will override the necessity to conceal our mouths.

We will take the risk to remain unmasked, and in doing so risk others.

There is no training in place to prepare a teacher for wearing a mask in front of a class.

When it comes it will be a moment of unwanted artifice and sadness, bearable not only because it is is reflected back by those who look to us for a moral, as well as academic, lead, but because it will be short-lived, a momentary pause in the ongoing exchange of understanding that is at the heart of the relationship between teacher and pupil.

David James is deputy head (academic) at a leading UK independent school