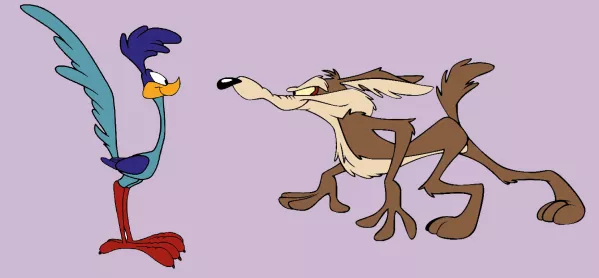

The Bloods and the Crips, the Montagues and the Capulets, Road Runner and Wile E Coyote: all bitter rivalries in which no quarter is given, where the very sense of the protagonists’ being comes from their never-ending mission to assert superiority over the other side.

Add to that list the “trads” and the “progs”, a pitched battle of education ideologies that may seem alien in Scotland, but that is very much alive and kicking in England.

At the Global Education and Skills Forum in Dubai this month, I spent more time with more people who are shaping English education than I have ever done before - and it was a stark reminder of just how different things are either side of the border.

The traditionalists and progressives are locked in combat over the future of education in England, each seeking to set the tone for a system that has been thrown into a state of flux. Some see recent government reforms as the creator of a Wild West of opportunity, where you can stamp your personal mark on education; others see a “rickety” and “unstable” system whose patchwork offerings resemble education in the Victorian era (see bit.ly/ProfBall).

Interestingly, however, whoever I spoke to, wherever they stood in this battle of ideas, when I mentioned that I was from Scotland, the reaction was likely to be the same: they would cock their head and furrow their brow in sympathy and ask “Where did it all go wrong?”

In the same way that many people in Scotland look aghast at what is happening in English education, many English educators perceive a tale of steep decline north of Hadrian’s Wall.

Scotland used to provide the model of excellence others aspired to, one person told me; then came Curriculum for Excellence (CfE) - those three words uttered with no little disdain - and a descent in the Programme for International Student Assessment (Pisa) rankings.

Scottish education is a very different landscape - one in which it’s hard to think of anyone prominent who would fall into the trads’ camp if transported to England. Some 96 per cent of pupils go to a state school, usually their local one, and you’d be hard-pushed to find anyone at a Scottish education conference who didn’t think local authorities still had a central role to play in children’s schooling. Arguments around CfE, meanwhile, invariably concern problems of implementation rather than whether it was a good idea in the first place.

Education secretary John Swinney has, of course, rattled some cages with his proposed reforms, such as the idea of devolving more power to headteachers, but these look rather vanilla compared with the exotica of English educational reform.

It’s never a bad idea to step outside your bubble and see how others see you. While supporters of Scottish education might describe it as a coherent system, others see conformity. While some will say Scottish education is relatively settled, critics see it as moribund. And while many in Scotland rejoiced when Teach First’s hopes of making inroads north of the border - the nearest thing Scottish education has had to a culture war in recent times - came up against a brick wall in 2017, delegates from England in Dubai struggled to understand why Scotland wouldn’t at least try this different, fast-track approach to teacher recruitment.

The epitaphs for Scottish education from distant observers may have been premature and, certainly, were at times over the top. It was energising and thought-provoking, however, to hear their views and see holes picked in common assumptions. Dissenting voices sharpen the mind and prompt an important question: are there enough contrarians in Scottish education?