- Home

- SQA results: The ‘exams debacle’ without exams

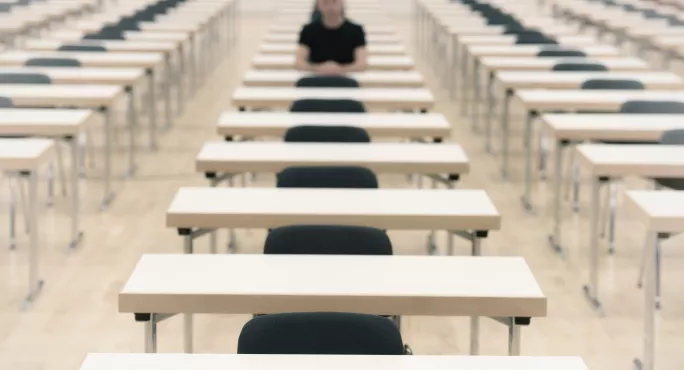

SQA results: The ‘exams debacle’ without exams

On 12 August 2000, the SQA chief resigned because of the “exams debacle” around Higher Still. The education secretary at the time was resisting calls for resignation. This will sound familiar given the current controversy over the latest SQA results.

Ironically, the opposition education spokesperson leading the calls for a resignation in 2000 was Nicola Sturgeon, who said the education secretary “has to go”.

Again, this is strikingly familiar. The current circumstances are completely different, of course - we should not understate the devastation and disruption caused by Covid-19. Yet the SQA results situation is not without precedent. The game of political football around education carries on being played, determined by underlying issues of power, injustice and inequality.

The first and deputy ministers were right to apologise about the latest SQA results and to act decisively. However, this could have been avoided. It was entirely predictable and the scale of the challenge was clearly beyond the abilities of statistical modelling.

SQA results: How the SQA defended the results fiasco

Also today: ‘Serious doubt over independence of SQA exams system’

SQA controversy: ‘We need a system we’re all confident in’

SQA results U-turn: ‘I am dreading the next few weeks’

Are exams still fit for purpose? ‘The SQA results debacle reveals deeper weaknesses’

Analysis: SQA exam system ‘has largely maintained the status quo’

Now, we have a situation where the very meaning and value of these results can legitimately be brought into question by universities, employers and others. Perhaps this was true all along: there is a bigger philosophical discussion around the role of schools and exam results.

Ivan Illich argued in 1971 that selection on the basis of prior education is just another form of discrimination. Indeed, as pointed out to me on Twitter, the 1947 Advisory Council report on Scottish secondary education stated that external examinations were “one of the greatest obstacles” to the ideals of education (see Fyfe Report, 1947, para 197-198).

Why do we adhere to a system where exam results - at best an unreliable proxy measure of ability and learning - determine subsequent opportunities for young people? Why do we cling to myths of social mobility?

A stubborn attainment gap is inevitable while social inequalities persist and deepen. No amount of innovation - pedagogical, algorithmic or bureaucratic - can counter the effects of social inequality. The latest political crisis about SQA results could turn out to be an important catalyst for fundamental change, but only if it leads to real dialogue and a shift in power. As the Higher Still fiasco in 2000 shows, we have been here before, and crises do not necessarily lead to sustained improvements.

John Swinney’s announcement of an expansion of university places is to be welcomed and can go some way to compensate for the botched results. This can ensure that more Scottish-domiciled students, including those who need additional support, can further their education (as indicated in comments from Anton Muscatelli, principal at the University of Glasgow). All is not lost.

However, this is not enough. Many young people will continue to miss out. Surely a national job guarantee and/or basic income scheme for young people, and other policies for economic recovery such as those being developed by Common Weal and the Wellbeing Economy Alliance, are now necessary.

The SQA results controversy reveals some of the enduring political and economic interests in Scottish education: we still have a stubbornly hierarchical system dominated by a “leadership class” (as Walter Humes has long said).

Government ministers and the policy community, once again, simply ignored the concerns and warnings of critics. It cannot be right that these debates mainly play out in the press or parliamentary chambers, where education inevitably becomes a political football for opportunistic agenda-setters to have a square go. Whoever wins the contest, it is “the system” that ultimately wins and remains roughly the same. We are trapped into thinking that radical change is not possible and that education will always be a crude sorting of winners and losers.

Illich’s solution was to “deschool” (or de-institutionalise) society completely. Most philosophers of education would now recognise this as an important but flawed thesis, as did Illich himself eventually did.

If anything we need to “re-institutionalise” education and society around the principles of social justice, so that progress is not determined by the volatility of markets, domestic politics or global shocks. Addressing the “poverty-related attainment gap” is vital but it barely scratches the surface of what is needed. Given the context of pandemic and long-term economic decline, we need to be radical.

Above all, we need to work out how to transcend short-term vested interests in the longer-term interests of young people, with young people themselves at the front and centre of that discussion, however clichéd it might sound - it is their future after all.

Gary Walsh is an education researcher and writer specialising in philosophy of education, citizenship and social justice, based at the University of Glasgow. He tweets @PeopleValues. This piece is a version of a post on his blog.

Register with Tes and you can read five free articles every month, plus you'll have access to our range of award-winning newsletters.

Keep reading for just £4.90 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £4.90 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £4.90 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters