‘Stop medicalising pupils’ normal tensions and anxieties as mental health conditions’

Share

‘Stop medicalising pupils’ normal tensions and anxieties as mental health conditions’

Why am I not surprised to read that heads’ union the NAHT claims that a fifth of children have mental health problems before the age of 11? Because in the UK, the existential troubles and anxieties of childhood are increasingly interpreted through the prism of mental health. Children’s mental health is perceived as a condition that needs to be “improved” in to order to avoid psychiatric problems later in life. Consequently, the normal tensions and apprehensions faced by school pupils are regularly perceived as medical and mental health problems.

Since the 1980s the manufacture of child-related mental health pathologies has been a growth industry. Report after report claims that mental illness among children is on the rise. Such reports insist that children are more stressed and depressed than in the past. Children’s behaviour is constantly portrayed with a psychological label.

Confused and insecure children are likely to be diagnosed as depressed or traumatised. Virtually any energetic or disruptive youngster can acquire the label of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Youngsters who give their teachers a hard time or argue with adults are likely to get stuck with the label of oppositional defiant disorder.

The proliferation of new medicalised categories with which to label school pupils says far more about the inventive powers of the therapeutic imagination than the conditions of childhood. Pupils who suffer from shyness are offered the diagnosis of social phobia. The diagnosis of school phobia can now be applied to label those children who really dislike going to school.

The transformation of the negative and anxious attitudes towards examination into a stand-alone category of exam stress shows how age-old sentiments and reactions to pressure are today recycled in the language of mental health.

Last year it was reported by the NSPCC and ChildLine that during a 12-month period the number of students who raised concerns about exam stress in counselling sessions grew by 200 per cent. Anyone who has been a child or understands children’s emotional life is unlikely to be surprised by the discovery that many pupils are concerned about their performance in an impending exam. What has changed is not the reaction of children but the rebranding of this response as the therapeutic category of “examination stress”.

From a sociological perspective, what is noteworthy about the alarmist accounts regarding the epidemic of exam stress is that children referred to this diagnosis in their counselling sessions. Children have become socialised into interpreting their experience through the language of mental health deficits. That is why, unlike children who went to school 30 to 40 years ago, today’s pupils readily communicate their problems through a psychological vocabulary and use words like “stress”, “trauma” or “depression” to describe their feelings.

Undermining resilience

In its report this week, the NAHT argues for more resources for dealing with children’s mental health issues on the grounds that schools play a “vital role” in building children’s “resilience”. Promoting young people’s resilience is a worthy cause but regrettably the tendency to medicalise children’s lives contradicts this objective.

Often initiatives designed to support children’s psychological wellbeing are founded on the conviction that children are anything but resilient. Many professionals involved in the field of child care and education possess an inflated conception of children’s vulnerability to emotional damage. Consequently, any child who is confronted with adverse circumstances in their lives is assumed to benefit from mental health intervention.

Through medicalising children’s normal emotional upheavals, young people are trained to regard the challenges integral to growing up as a source of psychological distress. That is why in recent decades, some educators and mental health professionals have adopted the practice of representing the transition from primary school to secondary school as a traumatic event for children. Instead of discussing children’s arrival at “big school” as an exciting opportunity, experts offer transitional counselling for what was regarded, for decades, as a normal and banal aspect of young people’s lives.

Transitional counselling, like many forms of routine mental health intervention with children, has a habit of turning into a self-fulfilling prophecy. Once children pick up on the idea that going to secondary school is a traumatic experience, many of them may interpret their normal anxieties and insecurities through the idiom of mental health problems. Instead of gaining resilience, children who are instructed to interpret their life experiences in medicalised terms may well become disoriented.

What children need from adults is not a diagnosis but guidance, inspiration and understanding. Schools that wish to cultivate children’s capacity for resilience should resist the temptation of medicalising their pupils’ behaviour.

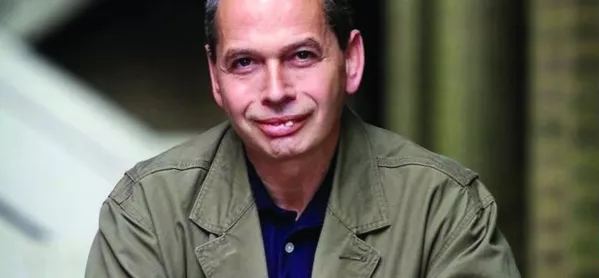

Frank Furedi is emeritus professor of sociology at the University of Kent

Want to keep up with the latest education news and opinion? Follow TES on Twitter and like TES on Facebook