- Home

- The Tes profile: Science advocate Becky Parker

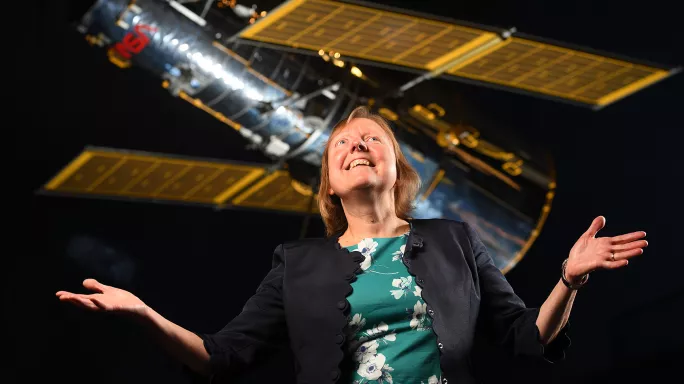

The Tes profile: Science advocate Becky Parker

After being taught about the Reformation for the fourth time, Becky Parker complained about her high-school history lessons.

At a parents’ evening, her teacher asked whether she was enjoying the subject.

“I don’t think I was cocky, but I was to the point,” she recalls. “I said, ‘I’m fed up with doing the Reformation, sir’, and he got hoity cross and said, ‘Well, if you don’t like what we’re doing, you teach a lesson then’.

“I said, ‘Alright then,’ and I must have been 12, and I taught a whole lesson on Roman Britain to my class and everybody loved it and I really enjoyed teaching.

“I suppose in the back of my mind I’ve always had a thing that I quite liked teaching.”

It is an anecdote that captures the energy, positivity and can-do attitude of an individual who has been a leading light in science teaching.

And now, as director of the Institute for Research in Schools, it’s Parker’s job to encourage more pupils to do real-life science, and more teachers to be active professional scientists.

Lying on the cliff top looking at the stars

If the seeds of her future teaching career were planted at secondary school, the passion that took her into the world of science has its roots in her sixth-form years.

“I saw an astronomy evening class further down the road in Devon, and I had passed my driving test. I used to drive me and my mum in my little Hillman Imp and actually lie on the cliff top looking up at the stars and thinking, ‘My goodness, what is this?’”

That interest took her to the University of Sussex, where her physics degree included not just science itself, but also a course about the social dimensions of science, which encompassed history, philosophy and science policy.

She then went on to the University of Chicago, but hit a hurdle when it turned out that no one had told her she needed a master’s degree rather than the BSc she brought with her.

So on her first day - “with my case and a bassoon, I looked like a gangster” - she faced a one-hour interrogation with a professor who specialised in relativity to check if her physics was up to scratch. It was.

Her time at Chicago soon provided a literal illustration of the difference between the sexes in her chosen field.

“The thing which is one of the key moments was they took a photo of all the first-year graduate students, because half of them will probably end up as Nobel laureates and they want to claim all that, and I was the only woman in the picture,” Parker says.

She got involved in groups looking at the issue of women’s under-representation in physics, but “I just thought their approach was too top-down. They were saying, ‘We need to get more professors.’ I was saying, ‘No, you’ve got to get them into school first.’”

Taking 100 pupils to CERN

Years later, as head of science at Simon Langton Girls’ Grammar School, in Canterbury, she “upped the number of girls doing physics - we had the biggest number of girls doing physics in the country”.

Getting more girls interested in Stem subjects has been a persistent goal of policymakers for years, so what did Parker do that worked so well?

The list sounds exhaustive, as well as exhausting, but it is delivered with her trademark breathless enthusiasm. “I did loads of stuff…” she begins.

“I took them to CERN [the European Organisation for Nuclear Research in Switzerland]. I used to take 50 kids and then 100 kids a year, as my numbers grew.

“I worked with the local boys’ school to run a big physics club. I got more involved in doing proper research projects.

“There’s a small group of us that got particle physics into A level, and that was really exciting.

“I used to take them to the cinema, take them to see Arcadia or Hapgood at the National Theatre.

“We used to run loads of different events at school. I built up a whole resource centre where they could find interesting books…”

Girls don’t want to think ‘I’m a woman in physics’

But the most notable thing about the range and variety of this work is that none of it was designed to appeal specifically to girls.

“To be honest, I hate all these ‘women in physics’ initiatives,” she says. “They drive me mad, because actually my girls just want to do stuff. They don’t want to think, ‘I’m a woman in physics.’”

Parker repeatedly jabs the table with her finger to emphasise her point: “I just think make it interesting so that all young people can contribute and feel they are valued members of the physics community and they will see there is a role for them.”

Over the past 30 years, Parker’s career has seen her cross back and forth over the line that separates what goes on in schools and what goes on in the scientific world, and her key message is that this divide should be porous, both for young people and for their teachers.

An epiphany of sorts came in 2006, when Faulkes Telescope - a professional robotic telescope project - was opened up to state schools.

Parker’s school became a regional centre in the South East, and hosted a day when local astronomers and physics teachers came along. Some of her students asked if they could use the telescope.

“That was a real turning point, because the kids found new near-earth objects, and got them registered at the Harvard Minor Planet Centre, and I said to my head, ‘These kids are doing this, why don’t we hand over some responsibility to the kids?’, and that was really the start of allowing young people properly do research.”

‘Research projects accessible to young people’

Today, Parker is the director of IRIS. Registered as a charity in 2015, and based in the Wolfson Building at the Science Museum in London, it has seven employees across the country.

“Our vision is to allow school students and their teachers to be a valued, contributing member of the scientific community,” she says, “and so what we do is we make research projects accessible to young people either through lending out equipment or making data accessible or by giving a structure where practical work can start and then develop into different new things.”

In chemistry, one project allows school students to develop new ionic liquids.

Parker enthuses about this “amazing class of new material” that does not evaporate, and adds that “in one school there’s such interest from industry that actually the ionic liquid which they have made can be used as a solvent for vacuum companies”.

Another project involves more than 1,000 students annotating the genome of the whipworm - a parasite that causes a tropical disease that affects countless children living with poor sanitation in the developed world.

“The thought, when the young people are getting stuck in, that they might help enable their peers across the world to go to school is a really big driver,” she says.

Combining science teaching and research

And Parker is evangelical about the model that sees science teachers spend one day a week carrying out research with students, and four days teaching.

“Teachers like me become enthused because they are actually doing the subject they love. I love physics. I want to inspire people in physics.

“Other physicists often don’t get very many opportunities to do physics, to do applied sciences. The number of teachers who have said, ‘This is keeping me in teaching, this has reinvigorated me.’”

Research by IRIS asked teachers what they had got out of this approach, and the benefits were wide-ranging, from reclaiming their identity as a scientist and being valued in the scientific community, to becoming better teachers and getting sustained CPD.

She says the project has more than 250 schools that are “very involved”, with 650 associate schools.

And Parker believes that it is an approach that could help to address the recruitment and retention crisis in science teaching: “My take about the shortage of Stem teachers is that I know they can go and get other jobs, but I think too often [science teaching has] been made so rote, with no scope for their passions, and I think that puts people off going into teaching.”

IRIS is now working to build up evidence to show headteachers the impact that its teacher-scientist model has had on increased aspiration and teacher retention.

Hers is a generous, all-embracing vision of what science can be in schools.

“The thing about science, in my view, is there’s too much just to not let kids really get a piece of the action,” she says.

Becky Parker: CV

Education: Preston Primary School and Whitehill School in Hitchin, Hertfordshire; Woodroffe School in Lyme Regis; University of Sussex (physics); University of Chicago (MA in conceptual foundations of science); University of Sussex (PGCE in secondary physics)

1986-87: Taught at Boundstone Community College in Lancing, now Sir Robert Woodard Academy

1988-90: Ran physics education at the Institute of Physics

1990-92: Head of physics, Godolphin and Latymer School, Hammersmith, London

1992-94: Head of sixth-form science projects at Saffron Walden County High, Essex

1994-2001: Head of science at Simon Langton Girls’ Grammar School, Canterbury, Kent

2002-05: Part-time senior lecturer in physics, University of Kent

2005-17: Head of physics and director of the Langton Star Centre, Simon Langton Grammar School for Boys, Canterbury

2016-present: Director of the Institute for Research in Schools

Register with Tes and you can read two free articles every month plus you'll have access to our range of award-winning newsletters.

Keep reading with our special offer!

You’ve reached your limit of free articles this month.

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Save your favourite articles and gift them to your colleagues

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Over 200,000 archived articles

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Save your favourite articles and gift them to your colleagues

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Over 200,000 archived articles