- Home

- Those teacher anxiety dreams? A handy revision tool

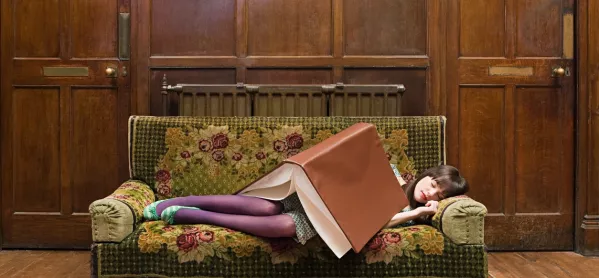

Those teacher anxiety dreams? A handy revision tool

I’ve always had spectacular dreams. I once competed in the Olympics, flipping a 20-metre fried egg on a giant hotplate, surrounded by cheering crowds. Russia were disqualified on a technicality and I won the bronze.

But my most vivid and terrifying dreams are work-related.

I suppose all professions have anxiety work dreams - building surveyors jolt awake from nightmares where they’ve searched in vain for a missing theodolite, for example, or dentists dream of being swallowed by a cavernous mouth bristling with decayed teeth…

But there’s a peculiar combination of performance, control and diligence required by teachers - one false move can lead not just to Year 8 misunderstanding the key elements of Oliver Twist, but to Year 8 running wild.

True, no one dies, but there’s a fine line between calm and chaos in the classroom, which can easily be thrown off balance.

Ofsted, with a Freudian twist

Throughout my working life, I’ve had many anxiety dreams: delivering a lesson on a cliff edge, with a murky pool below, or in a L-shaped room where more and more students swarm in and I can’t remember anyone’s name, or where I’m in the middle of assembly and I suddenly realise I’m wearing nothing but a flimsy bath towel.

At the most vulnerable part of the dream, Ofsted inevitably makes an appearance.

There’s usually a Freudian twist, where the inspector takes the form of my ex-husband, say, or Craig Revel Horwood, sneeringly holding aloft a score card with “-10” written on it.

It’s rare - I’d go as far to say almost unheard of - that my teaching dreams have a positive outcome. The moment I awake, realising that I don’t actually have to teach puppets to dance, is the most glorious, blissful relief.

Pride and Prejudice: the board game

However, last week, an idea for a lesson came to me in dream - and it was jolly good. I dreamed my Year 11s and I had devised Pride and Prejudice: the board game. Elements of Monopoly and snakes and ladders combined to create challenging and entertaining fun for all the family.

The details - as with all dreams - were hazy, although I have a vague sense that Lydia’s elopement sent all the Bennet girls down the scaly coils of Wickham, back to square one and miles away from the winning square of Pemberley.

In the car, on the way to work, I considered sharing the idea with Year 11, who are plodding unenthusiastically through their P&P revision. I’ll be honest here: no amount of dramatic rendering of Lady Catherine’s least reasonable outbursts are firing their imaginations, and I was at a bit of a loss.

As I reached the airport roundabout - the halfway stage of my daily journey - a new idea hit me: Pride and Prejudice Top Trumps! Perfect! Although…

… although, I have to explain that I lived through the years of the national strategy. We were lectured at Inset that lessons had to be fun, that the children should leave our classrooms with smiles on their faces, that the best way to teach Shakespeare was to get our students to write a relevant quotation on a piece of paper, fashion the piece of paper into an aeroplane and throw it across the room, where another student would unfold it, read the quotation and remember it for ever.

I’m not averse to fun. Fun, with the appropriate checks and balances, is acceptable. I have been known - on occasions - to give in to fun.

But, if anything could put a woman off fun for life, it’s ill-judged educational fun that leads to the kind of chaos that haunts my nightmares. More than anything, it was being advised to make an enormous pass the parcel to teach Year 7 how to parse a sentence that led me back to traditional chalk, talk and relentless practice.

Subconsciously inspired Top Trumps

But, in the end, I couldn’t resist. I ditched my lesson on GCSE language paper two Q5, and shared my Austen inspiration with my Year 11s.

Immediately the room lit up. First, we agreed on categories, ending up with a wide range: accomplishments, beauty, intelligence, manners, morals, property, propriety, rank, responsibility, sense, sex appeal and wealth.

The class who’ve been struggling with the nuances of the early 19th-century class system could suddenly see the distinction between money and status. The light of understanding dawned when it became clear that Mr Darcy behaves with propriety, but that his manners leave a lot to be desired.

The class divided into pairs and took a character each. They had to find a brief quotation to describe their character and to award a percentage in each category - which had to be justified if challenged.

There was fierce discussion about whether Mary was more or less intelligent than Elizabeth, and who was the sexiest: Mr Wickham or Mr Darcy (I was overruled and Wickham won).

It was noisy, it was intense, it was fun and, even with my most Gradgrindian hat on (now there’s a stylish idea), I have to admit that they learned a lot.

There’s a rich educational seam to be mined here. At this very moment, I’m working on my ResearchED presentation: In Your Dreams: how your subconscious can plan your curriculum.

Don’t laugh! It’s the future.

Sarah Ledger has been teaching English for 33 years

Keep reading for just £1 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £1 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters