Attainment in UK schools suffers more than average from poor pupil behaviour compared to most of the rest of the developed world, according to the official in charge of the influential PISA study.

Andreas Schleicher also cast doubt on the use of exclusions – which have been rocketing in England – to improve discipline, saying it was better for teachers to spend more time with pupils.

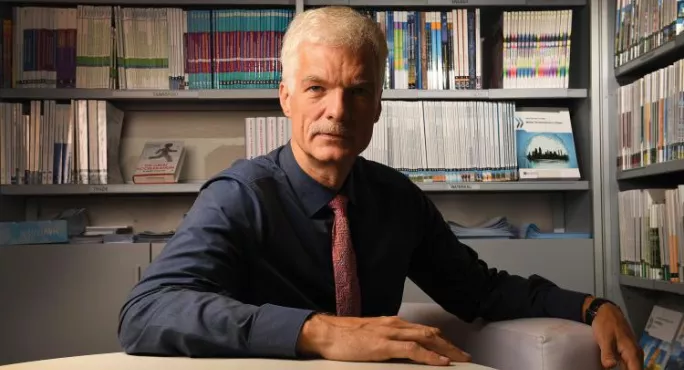

The OECD's education director, who runs PISA (the Programme for International Student Assessment) did not say that pupil behaviour was worse in the UK. But he said that it had more impact when it was poor.

“Discipline is an important variable internationally [on pupil attainment]," Mr Schleicher told journalists today. "In the UK, it’s more important than on average across [OECD] countries.

“It’s basically discipline and the social profile of schools that are the big drivers [of attainment] in the UK.”

He said measures such as time lost to disruption in class and the strength of pupil and teacher relationships were “very strong predictor[s] of academic outcomes”.

But Mr Schleicher spoke out against the use of exclusion to tackle discipline. “I don’t think really that exclusions are actually a promising variable to create positive discipline. Nor are tracking and streaming,” he said at the launch of a new study of education in OECD countries.

On the contrary, he said, in many countries included in the study “you have a very strong disciplinary climate in schools were exclusion is never an option”.

His comments come amid a growing debate about the problem of rising levels of exclusions from England's schools. Latest official figures show that permanent exclusions have shot up by 15 per cent in just a year.

The two-year OECD study, launched today, paints a grim picture of how pupils’ socio-economic status shapes their lives from primary school. It also shows how deprived UK pupils are among the unhappiest in the OECD, coming second only to Turkey in terms of “social and emotional resilience”.

Mr Schleicher said this could be addressed by incentivising teachers to work in disadvantaged areas and giving them more time to spend with individual students.

He pointed to the example of Finland, where teachers can spend 30 per cent of instruction time in out of classroom activities.

“If you have a really difficult group of students, you want to be able to spend time with them,” he told reporters. “In England, you run to your next class.”