Abridged versions of texts exist to allow wonderful stories to be retold without the barrier of complex vocabulary and sentence construction. They can come in the form of graphic novels or audiobooks, and can allow late starters to get up to speed with an exam text or provide an alternative way in for a student who has difficulty accessing the original text. They allow them to overcome the plot complexities before they begin the language analysis.

What abridged versions don’t do is replace the original text.

As term winds down, we are now in the time of great restructuring: heads of department everywhere are looking at their key stage 3 plans, and wondering where improvements can be made in light of what we know KS2 are arriving with, and KS4 are expected to start with.

Striking the balance

A key part in this process has to be asking your primary feeder schools which texts they are studying at KS2. Often, the answers come back along these lines: Macbeth and Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde.

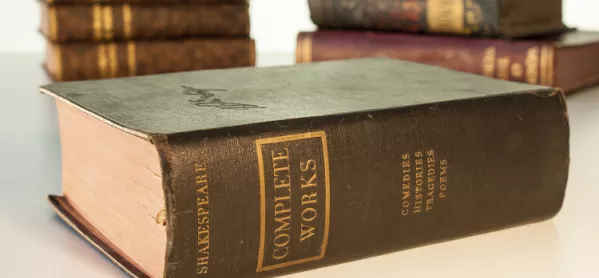

Of course, these GCSE texts contain language that is far too complex for primary-aged children - so, instead, abridged versions are used. But if you haven’t read Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde by Robert Louis Stevenson, then you haven’t read Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde. And if you choose to do this text with a class of 10-year-olds, then you’re robbing them of the chance to read the reveal of Mr Hyde’s true identity in the words that Stevenson wanted us to read.

And there’s another problem, too. Macbeth is an exam text, so it is highly likely that students will encounter it again in secondary.

We want to expose children to as many texts as possible. Studying Macbeth in KS2 and then again in KS4 limits students; when a class learns they are doing a text they did in primary school, they often feel irritated (“We’ve done this, Miss!”) or falsely confident (“Yeah, yeah we know this”) or else key points that are skimmed over to make it age-suitable in primary are then confusing in secondary (“This wasn’t in it before!”). Although it only takes a bit of persistence to overcome, it all feels rather avoidable.

‘Don’t raid the GCSE cupboard’

Fortunately, Stevenson wrote children’s books, too, and his Treasure Island is a perfect class reader. Journey to the Centre of the Earth by Jules Verne is challenging, and is also a suitably weighty, well-known text. Chinese Cinderella by Adeline Yen Mah is full of wonderful descriptive passages, as well as a compelling plot. Roddy Doyle has written a lot of great novels for younger readers. There is absolutely no need to raid the GCSE cupboard to find good texts for primary or KS3.

AQA lists Macbeth, Romeo and Juliet, The Tempest, The Merchant of Venice, Much Ado About Nothing and Julius Caesar as options for GCSE. Edexcel includes Twelfth Night instead of Julius Caesar and Eduqas includes Henry V and Othello. This leaves lovely rich pickings of Shakespearean texts to study at KS2. Here are just three that are perfect for primary.

1. A Midsummer Night’s Dream

A fantastic introduction to Shakespeare. There is the play within a play and a donkey. Who doesn’t love a play with a donkey in it?

2. Antony and Cleopatra

A fabulous play to work into a curriculum. You’re working with characters who students already recognise, and there is jealousy, love and a bit of a battle. Oh, and the snake.

3. Measure for Measure

This one has a real treat of a plot: a duke in disguise, a nasty baddie and a head swap at a public beheading. It is a fantastic base to build upon for the KS3 and 4 Shakespeare experiences.

Grainne Hallahan has been teaching English in Essex for 10 years. She is part of the #TeamEnglish Twitter group