- Home

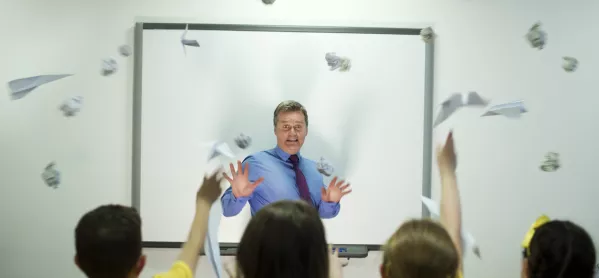

- What if Covid policy were a school behaviour strategy?

What if Covid policy were a school behaviour strategy?

Stay at home - Protect the NHS - Save lives.

Stay alert - Control the virus - Save lives.

Hands - Face - Space.

What next? Hop - Skip - Jump? Yabba - Dabba - Doo?

The government’s rule-of-three approach to getting the nation to change our collective behaviour (and, crucially, to maintain those changes for a sustained period) to limit the transmission of the coronavirus is an ongoing case study in mismanagement.

While I do have a picogram of sympathy for the scale of the task that the government faces, that vanishes faster than a pack of doughnuts in the staffroom when we look at the ways that it has tried to convince us to behave differently.

It is difficult to see how we, as teachers and school leaders, could retain the confidence of our teams, our students and their parents if we tried to improve behaviour in our schools in a similar way.

Confused messages over the coronavirus

Early in lockdown, I was a regular viewer of the daily briefings. I appreciated the information that was being provided, and the questioning of ministers and scientists by journalists, including those from Tes.

Sharing complex information in an accessible and clear way is not easy, so it was helpful to understand key indicators, including the R number, hospitalisations and, sadly, deaths.

But then the government started fiddling with the messaging. It changed the way that it presented comparisons of our rates with those of other countries - a sure sign that the numbers had the aroma of a prawn sandwich left in the staffroom fridge over Easter.

Then it rambled. Ministers droned on about world-beating testing systems or a game-changing app, before going on to announce that, by the way, deaths had risen again. It reminded me of a headteacher writing to parents about how much Ofsted liked the new carpet in Reception and, by the way, the school is now in special measures.

We tuned in for reassurance, not a party political broadcast. Without that reassurance, our willingness to do what was required started to wane.

Teachers and school leaders are no different. We can convince our colleagues to persist with changes to behaviour systems if they can see that what they are doing is working.

This is most important when things are tough. We were having just such a conversation in a staff meeting yesterday. We are struggling to support a child to behave well at the moment. It is difficult to keep faith at times like these, but a comment from a TA who knows the child well, saying that they have improved markedly since last year, gives us the push we need to keep going.

Significant and lasting behaviour change takes time. But, to sustain effort, you do need evidence along the way that what you’re doing is effective. And if the evidence says that what you’re doing is not working, then you need to admit that and change tack, not blame the staff and the child, as the government is doing with the population at the moment.

Clear and coherent rules

Are you clear on the current rules about what you can and cannot do? I do know that my family cannot visit my parents while my siblings and their children are there. Tough to accept, but fine given that none of us wants to kill my parents with this virus. We can, though, all go grouse shooting together - and bring along 18 of my cousins, too.

There are three things about the coronavirus rules that make total adherence challenging:

1. Ideally we want people to follow rules because it is the right thing to do. We accept the need to wear a mask, self-isolate or not go grouse shooting in a group of 31. This intrinsic motivation is powerful and requires no enforcement.

2. If our support is shaky, and we struggle to accept that rule-following is good even if we don’t like the rule, then rules have to be enforced. Things start to feel more oppressive and a sense of injustice can build up. All school leaders know, as do the police, that we lead (and police) by consent. Getting buy-in from our community for our rules gives us the best chance of adherence and support. Without it, we rely heavily on enforcement, and that means a lot of adults out and about to catch rule-breaking individuals, who will find ways to evade detection because they judge the risks of being caught as acceptably low.

3. Rules have to make sense for us to support them. Exceptions like grouse shooting just make the government look ridiculous.

Humility: the leader’s best friend

Humility is a leader’s best friend. I have an aversion to hubris and arrogance. I worry that hubristic leaders are focused on meeting their own needs, at the expense of the rest of their organisation, whether that’s a country or a school.

We don’t need to be world-beating when it comes to the coronavirus. Why on Earth would we want other countries to do less well? Headteachers don’t want children in the school down the road or across town to behave poorly. It is possible for all countries to do their best with the resources they have, and to benefit from support from other countries, in exactly the same way that it is possible for all schools to have exceptional behaviour and to support others to achieve the same.

When things are going well, leadership seems like a piece of cake. It isn’t, and the best leaders know this, which is why they don’t let up.

But when things aren’t going well, everyone knows it, no matter how much you say to the contrary. The humility in leadership comes from knowing - and admitting - what is not working well, and tenaciously tackling it.

If our government took this approach with testing, I think it would find that the nation would be much more sympathetic to its efforts. Instead, we have Jacob Rees-Mogg criticising us for “carping” when we should be celebrating. Forgive me if I don’t break out the party poppers just yet.

Hypocrisy: undermining your own rules

It only takes one gutless leader to support one shameless rule-breaker and it shatters any illusion that we’re all in this together. Had Dominic Cummings been sacked for his pathetic refusal to follow the rules like most of the rest of us, we would all have supported the decision as good leadership and swiftly moved on, content that Cummings would spend the rest of his days blogging furiously about how he alone had predicted the Covid outbreak.

My friend and fellow behaviour expert Mark Finnis asks: “Is the culture in your organisation by design or by default?” This is a great question, because a poor culture can grow, like mould, unchecked in the gaps, if you don’t constantly take steps to develop it in the way you want.

My grave concern about this government’s culture, typified by its approach to the coronavirus, is not that its culture is a poor one - it clearly is - but that it is also by design.

Jarlath O’Brien works in special education and is the author of Better Behaviour - A Guide for Teachers and Leading Better Behaviour - A Guide for School Leaders

Keep reading for just £1 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £1 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters