- Home

- Why the Dead Poets Society’s John Keating was right

Why the Dead Poets Society’s John Keating was right

It was the iconic 1989 film Dead Poets Society that sparked my initial interest in teaching. I suspect it did for thousands of my colleagues.

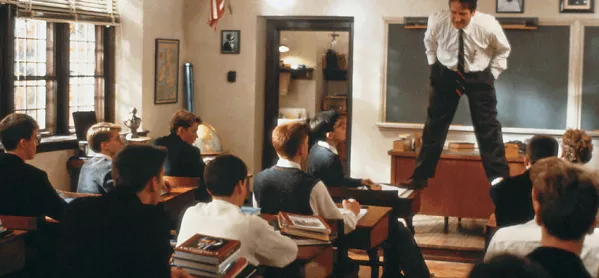

The main character, English teacher John Keating – played by Robin Williams – appeared the romantic antithesis to the education system’s dullness. He inspires students through novel, shocking methods: students jumping off desks; quoting poetry as they kick footballs; sneaking off into woods to read the romantic poets. Keating represents an ideal teacher we yearned for but perhaps never got.

Now in my third year of teaching, I’m more aware of the critique bordering on resentment against the film. I recently spoke to a teacher of 40 years who railed against its reckless vision of promoting the charismatic teacher working in isolation, undermining colleagues. When Keating has students rip out the academic introduction to a poetry textbook, a Latin teacher marches into the classroom in horror, presuming Keating isn’t present. What behaviour is Keating condoning in other classrooms? What iconoclastic arrogance does that nurture, if students are encouraged to simply dismiss academia?

Schools that struggle die by such inconsistency in behaviour routines; no teacher should be an island. In most schools, students would exploit, rather than shine, under Keating’s unstructured free-for-all. The strict teacher is the main defender against their worst impulses and perhaps the only guardian they have left of their future.

Keating is firmly in the progressive rather than traditional side of the education divide. In the opening scene, the oppressive "light of knowledge" is passed around the assembly hall. Keating rides in to counter the indoctrination, telling the headmaster that education should encourage students to think for themselves, not regurgitate facts. The headmaster quips back: stick to the tried and tested method to best prepare them for college.

In one scene, the Latin teacher’s class repeats back verbs – a traditional method I now realise will likely get them there. Basic education psychology indicates students "thinking for themselves" without knowledge generates hollowness. Students prancing around a classroom might seem less entertaining if the exam grade required to help get a child out of poverty is missed.

Yet despite this, the allure of Keating persists, for his approach offers a corrective to some of the fleeting dogmas in education today. Structures and routine are foundational to a school’s behaviour system, but they alone can’t break down the student-teacher divide that often blights schools. Keating transcends it, taking a non-adversarial, parental approach. He ushers one student into his office for tea and a conversation about an overbearing father. Teachers who command the affection and respect of students have the strongest relationships.

Escaping the exam factory

The "knowledge-rich" curriculum is very in vogue. But Keating reminds us that it’s how knowledge is presented that matters. When I ask non-teachers about their favourite teacher, they’ll affectionately talk of a teacher’s passion. Keating’s teaching of Robert Herrick’s famous line “gather ye rosebuds while ye may” is done in whacky way in the school entrance. But powerful moments stick in the memory. This knowledge is presented for its own value, a refreshing contrast to exam-obsessed schools. When one boy asks whether they’ll be tested on Keating’s teaching, another chides him: “Come on, don’t you understand anything?”

Schools often assign dubious target grades that label students: this student should get Grade 3 in Year 8 and Grade 6 by Year 11. Keating, too, shows the importance of raising the bar, but he makes the intellectual pursuit not just accessible but desirable to all.

A personal highlight from my teaching career was when a middle-attaining Year 7 claimed, “It is better to be feared than loved,” during a debate on the greatest Tudor monarch. A few weeks previously, we’d learned about Machiavelli’s ideas on leadership. He then applied that prior learning to a new context.

Keating’s core message is right. In an early scene, Keating shows his students old school photos of boys who were now “fertilising daffodils”. It was a striking way to convey that education is precious, something which many British schoolchildren appear to be unaware of.

The aspiration to get them inspired by learning is admirable. A teacher, a school, that can get students to value education as one of life’s gifts is one that has done their students the greatest of services. Get them to appreciate that, and the rest will follow.

Adam Seldon is a secondary school history teacher and head of character, charity trustee and writer. He tweets at @adamJseldon

Keep reading for just £1 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £1 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters