- Home

- Would Leonardo da Vinci have excelled in our school system?

Would Leonardo da Vinci have excelled in our school system?

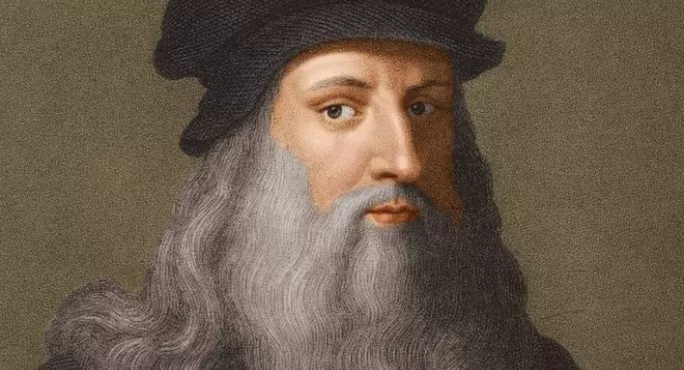

Leonardo da Vinci, the greatest polymath, and surely the best champion for human potential, described himself as an omo sanza lettere – a man without letters, without an education.

Were I to have a young Leonardo or Leonora in my school today, it would be hard to identify them from the attainment or progress data available to me. The way in which we measure intelligence today is so narrow that it would hide the voracious and prolific creative talents of another da Vinci.

Neither the models of assessment adopted, nor the methods of teaching and managing behaviour employed in schools are receptive or conducive to creative impulses and disruptive, rebellious thinking.

Perhaps this is why so many employers today are dissatisfied with the range of skills and proficiencies offered by even the best A* graduates, blessed with high computational capacity and a 97th percentile intelligence quotient. The multiple intelligences so eloquently described by Howard Gardner, and so deftly demonstrated by Leonardo centuries before, seem absent in all but the most enlightened examination systems upon which most school curricula are built. The 3Rs of reading, remembering and regurgitating still reign, but they may marginalise more creative geniuses than they empower. And employers know this.

Pearson’s insightful Employability Skills Gap reveals that less than 38 per cent of employers say that college graduates are prepared in the skills needed in the workplace. Eighty-five per cent of employers highly value communication skills, for example – but only 27 per cent say graduates have them. Critical thinking is highly prized, too, by 81 per cent of employers, but only 26 per cent of them believe their newly recruited graduates can think critically.

Such a gap in what graduates can do and what employers need them to do is matched by a widening gap in thinking by business and education leaders. In Pearson’s Employability at a Glance survey, 96 per cent of chief academic officers in the US said they believed their institutions were either very or somewhat effective at preparing students for the world of work: only 11 per cent of business leaders thought so. Encouragingly, though, 88 per cent of both camps favoured an increased level of collaboration between them, so there is a shared desire to do something about it.

Our myopic view of education is broadening, and we are putting on holistic lenses at last. It’s as if we have finally seen the shadows in Plato’s cave for the two-dimensional silhouettes they are and that there is more going on behind us. If school is the cave then the worlds of work and leisure await us outside – and they require hidden skills and tacit knowledge that were not revealed to us when we were inside.

Students are more than data processors

What has so enlightened us? How is that we can now see the multi-dimensional and dynamic nature of being human and how it is being sold short by the traditional model of education?

It is the prospect of artificial intelligence threatening our purpose and outperforming us in the very things we thought mattered most in school – information-processing, calculating and applying deductive logic – that has brought to us our senses, literally.

None of us can outperform the digital device in our hands. It doesn’t fidget and it doesn’t procrastinate. It gets on with the job. If it has senses at all, they are primed and ready to do a specific task and are not open to distraction. The student who can work like a computer – receiving, processing, retaining and recalling information efficiently and without distraction – will sail through school examinations. But for most us, data does not enter our central processing unit in 1s and 0s only.

There is more to being human than data-processing. Our senses equip us to deal with the unexpected hazards, challenges and beneficial opportunities that float past us daily. To anaesthetise students from such experiential learning is to reduce their human potential before they’ve even found it.

Einstein said: “The intuitive mind is a sacred gift and the rational mind is a faithful servant. We have created a society that honours the servant and has forgotten the gift.”

Intuition allows us to "know" something before we have analysed it rationally. It bridges the gap between our conscious and non-conscious mind. To intuit something is to subconsciously draw on one’s myriad sensory perceptions to reach a notion of what is going on around us, how we should respond and what we should do next. And our instinct guides us. The problem is, our rational mind often overrides any instinctive impulses and we reach a different conclusion based on reasoned analysis. Though rationality is precious, it can mislead us; it gives us a false notion of what human behaviour is.

Polyani’s Paradox tells us that we know much more than that which we can articulate. Tacit knowledge will always be our greatest asset as learners, no matter how much we ignore it in school and say it doesn’t count because it can’t be counted. But that’s just the point. Our ability to perform tasks intuitively, instinctively, is our best-kept secret and our greatest defence against the march of the robots. Computers require consciously accessible knowledge, but much of what we do as humans cannot be explained or transferred through data. This is the educator’s paradox.

In creating an education system built on accessible knowledge that is consciously learned and then tested, we have forgotten the things that matter most. And now that computers have caught us up and rapidly overtaken us, in many of the proficiencies taught in schools, we are realising that our educational agenda is flawed.

Manage your distraction, stay in your learning bubble, focus. Dehumanise if you can. For those incapable of staying on task we have a range of diagnoses available, and recommended strategies to help them switch off their creative impulses and sit still long enough for us to obtain an "accurate" reading of their academic intelligence. The negative impact which sorting and ranking has on human creativity seems to have been missed.

Meanwhile, outside the cave, leaders of business want intuitive, creative thinkers. Leaders of our communities want empathic, socially responsible citizens, sensitive to the needs of others. Inside the cave, leaders of the system want mini versions of themselves, with encyclopaedic brains, cursive handwriting and expedient levels of concentration. No wonder there is a gap in employability skills.

Rethinking the curriculum and assessment

At the International Festival of Education East in June 2019, leaders of all kinds will come together to consider how the technological age presents an exquisite opportunity to recalibrate what matters in schools. Information management systems and artificially intelligent marking systems will undoubtedly free up teachers’ time. Seductive technology like VR and AR will enrich learning experiences and raise student engagement, perhaps even bringing back awe and wonder to a young generation saddled with anxiety and cynicism.

These are exciting aims, but the greatest opportunity afforded by new technology is that it forces us to rethink the curriculum and assessment agenda once and for all – so that we can define students’ potential on what they can do that AI can’t. There is a mandate now for a new set of learning objectives – a curriculum that embraces the attitudes, behaviours and human capacities that lie behind the measurable grades (and which cannot be simulated artificially). There is no justification for continuing to use the 3Rs to define students’ learning potential or life chances, because it sells their talents short and does not deliver the skills needed in the workplace anyway.

If da Vinci were alive today, he would get his sketchbook out and design us a new school: one that delivers an aesthetic rather than anaesthetic experience, and one that rejoices in the creative potential of young humans.

But da Vinci was a man without an education, so what does he know?

Andrew Hammond is headteacher at Guildhall Feoffment Primary School, Bury St Edmunds. He is also a patron of the International Festival of Learning that takes place this year on 28 June 2019, partnered with Pearson and focused on the blend between technology and uniquely human skills. Tes is media partner

Keep reading for just £1 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £1 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters