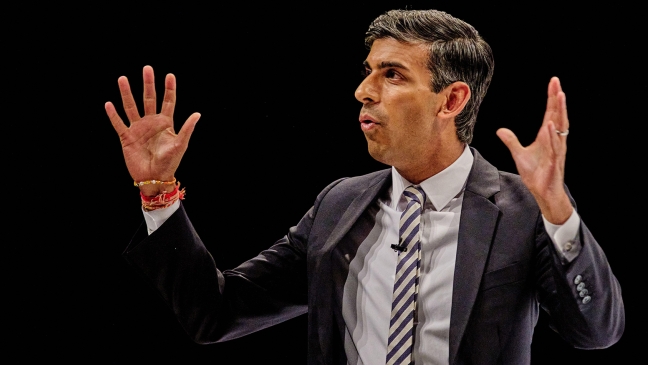

Rishi Sunak’s desire for a “British Baccalaureate” to replace A levels is back in the news having first surfaced during his failed leadership campaign.

It is, of course, not a new idea. Back in 1990, David Miliband, then a mere think tank wonk, proposed a British baccalaureate that would broaden the narrow post-16 curriculum and ensure all young people did some English and maths to 18.

Just over a decade later, when Miliband was schools minister he tried to make it a reality, bringing in Mike Tomlinson to create what became known as diplomas.

These were fatally undermined when Tony Blair decided the political costs of ditching the “gold-standard” A-level brand were too great, and were killed off when the coalition government arrived.

The difficulty of qualification reform

There were few complaints from schools, though much frustration about how much effort had gone into an ultimately futile exercise. Despite having seven years from the idea being proposed to losing an election, Labour still failed to make it stick. Qualifications reform is really hard.

Sunak only has one year and that will most definitely not be enough time to make anything substantial happen, beyond working up the idea for a manifesto.

He seems to have taken the idea from last year’s Times Education Commission, which didn’t offer much detail either.

It’s certainly not anything school leaders need to worry about for the foreseeable future. Labour is likely to roll it all into a promised general review of curriculum and assessment if, as seems highly probable, it wins the election.

What we should all be worrying about is that this is what is preoccupying our political leaders at the moment. It reveals a prime minister wildly out of touch with the reality of what day-to-day life is like for heads and teachers.

The entirely wrong focus

It’s not that the proposal itself - not that we’ve seen any details - is mad. After all, whether or not we should reform our qualifications system is something that’s been regularly debated over the decades.

It’s true that A levels are unusually narrow compared with the suite of subjects that pupils study in other countries. It’s a trend that has got worse over the past decade owing to heavy cuts to post-16 education leading to a reduction in taught hours, and the demise of AS levels.

But it’s nowhere near the top of the priority list right now.

Schools are struggling with a tight financial settlement, buildings are literally falling down, we’re only going to recruit half the secondary teachers we need this year, retention is getting worse, pastoral problems with student mental health and deep poverty continue to demand more attention, the SEND system is utterly broken. Throwing major qualification reform into that mix would destabilise an already painfully fragile system.

I have not resiled from my initial reaction on Twitter that the proposals are akin to attending a house fire and suggesting redoing the kitchen.

It’s also just an incredibly bad way to make policy. To date, all the work on this idea has been within Number 10, which has no one with substantive education experience in it. The DfE, hardly a hotbed of practical knowledge itself, has been excluded.

Neither of the headteachers’ unions nor the Confederation of School Trusts has been involved in developing proposals.

A lack of knowledge is a dangerous thing

I have always disagreed with the argument that “education should be taken out of politics” - it can’t be because it’s inherently political. But we definitely need politicians who understand the limitations of their knowledge.

Sunak can’t even claim to have gone to a normal school - Winchester is about as unusual as it gets - nor does he use state schools to educate his own children.

If he did, maybe he’d realise how tough things are and would be more concerned about fixing the fundamentals. There’s no point designing new qualifications - however good they are - if there’s no one there to teach them, and no resources to teach them with.

Sam Freedman is a senior fellow at the Institute for Government and a former senior policy adviser at the Department for Education