‘Something bad will happen’: how social care cuts hit exclusions

“I had to exclude four children this week - two definitely should have had a social worker, but they didn’t.”

For this headteacher, based in the East of England, a lack of social workers for students who would ordinarily have one is a clear trend, and it is a problem that has intensified over the past five years.

Without that support in place, the head says, making decisions around exclusions and suspensions is a lot harder because they know there are no other services to support the child once they are off the school site.

“I regularly go home worried about children,” the leader adds.

This is not just a moral issue, but a legal one, too. The Department for Education’s suspension and permanent exclusion guidance states that headteachers must “take account of their legal duty of care when sending a pupil home following an exclusion”.

Behaviour: the duty of care with suspensions

Although this particular piece of guidance does not mention suspensions, safeguarding lawyer David Smellie, of Farrer & Co, says that a suspension would “absolutely” be covered by that same duty of care.

Because of the social care situation that the headteacher in the East of England describes, schools are clearly now in a very tricky position regarding this duty.

When a student exhibits behaviour that puts staff or other children at risk, but that student would be at risk if excluded or suspended from the school site due to social workers not being in place, what should a school leader do?

- Suspensions: Students who are suspended “a year behind at GCSE”

- Behaviour: The scale of the suspensions problem revealed

- School policy: Why suspensions affect everyone in class

The guidance itself doesn’t offer much clarity.

On the one hand, it says that “for the majority of children who have a social worker, this is due to known safeguarding risks at home or in the community: over half are in need due to abuse or neglect”.

It adds that, for such children, education is an “important protective factor” that provides a safe space where they are “visible to professionals”. Whereas if they are not in school, they can miss the “protection and opportunities” school can provide, leaving them “more vulnerable to harm”.

Yet in the very same paragraph, the guidance says that leaders must “balance this important reality” with the need to ensure “calm and safe environments for all pupils and staff”.

While the challenge of getting this balance right has always existed, headteachers say it is now proving a lot harder.

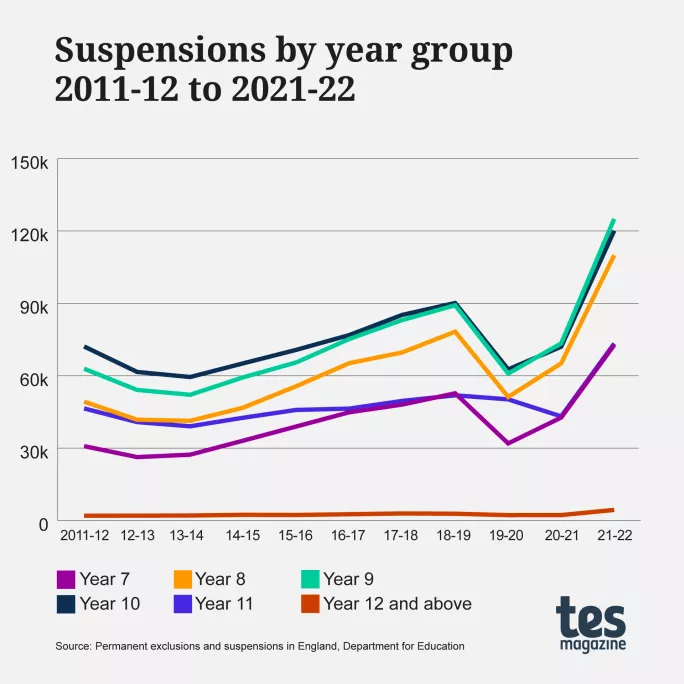

The need for suspensions and exclusions has risen post-pandemic, they say (see the graph below), at the same time as there has been a decline in wider external social care support.

The latter means that social services intervention, or the absence of it, is no longer a reliable indicator of the level of risk a child might face should they be excluded or suspended.

Off the record, multiple school leaders give examples of how this problem plays out day-to-day.

“We were considering suspension for a child we had done an inter-agency referral for but the case was closed,” one head explains. “But we still have concerns…so where do we draw the line? The behaviour does not meet our expectations but what are we going to do to make sure they’re safe?”

The head in the East of England says they regularly have to make decisions on students who they believe should have social worker support but do not.

“These are children where social care has been involved at various points but they keep stepping away and closing off the cases. We’re saying to social care, ‘We need you to be involved because we’ve got significant concerns,’ but they will do a visit and say, ‘It’s fine,’ but we can see clearly that it isn’t.”

“Support services have been cut to the bone”

It’s a situation that isn’t just affecting secondary schools. One primary head in the North West says they often receive no support when considering suspensions or exclusions for children for “biting, spitting and attacking teachers” when these children have unstable home environments.

“You used to get advice but now if you ring [the local authority], the message is, ‘If you feel you need to exclude, that’s up to you.’”

A wider insight into how isolated schools feel on this issue is provided by recent survey responses and government data.

Margaret Mulholland, special educational needs and disabilities (SEND) and inclusion specialist at the Association of School and College Leaders (ASCL), says it is clear that an “erosion of children’s services” is causing major difficulties for schools - a situation highlighted in a survey by ASCL in which 96 per cent of headteachers reported that children’s social care services were “inadequate”.

Meanwhile, a recent children’s commissioner’s report found that of almost 1 million children referred to child and adolescent mental health services (Camhs) in 2022-23, over a quarter (270,300) were still waiting for support, while 372,800 had their referral closed without any support.

Rob Williams, senior policy adviser at the NAHT school leaders’ union, says it is clear that “support services have been cut to the bone” and schools are now at “the coal face of challenging social problems”.

Big rise in referrals to social services

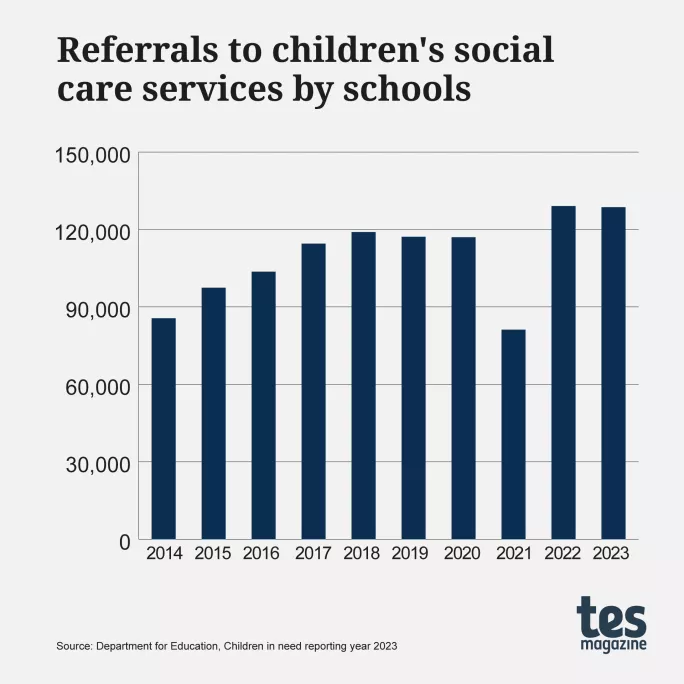

This reality is also highlighted by the huge rise in referrals to children’s social services by schools over the past decade or so, as other services have fallen away from frontline identification of at-risk children.

Specifically, in 2014 a total of 85,620 referrals were made by schools. By 2017, this had risen to 114,530 and then it increased to 117,010 in 2020.

A drop in 2021 to 81,180 referrals suggests a pause due to the upheaval of the pandemic because since then referrals have shot up to 129,090 and 128,650 in 2022 and 2023 respectively. This represents a 66 per cent increase in nine years.

This increase has led to a rise in the number of children in need, too, which has grown from 378,030 to 403,090 over the past ten years, while the number of children with a protection plan has grown from 43,190 to 50,780.

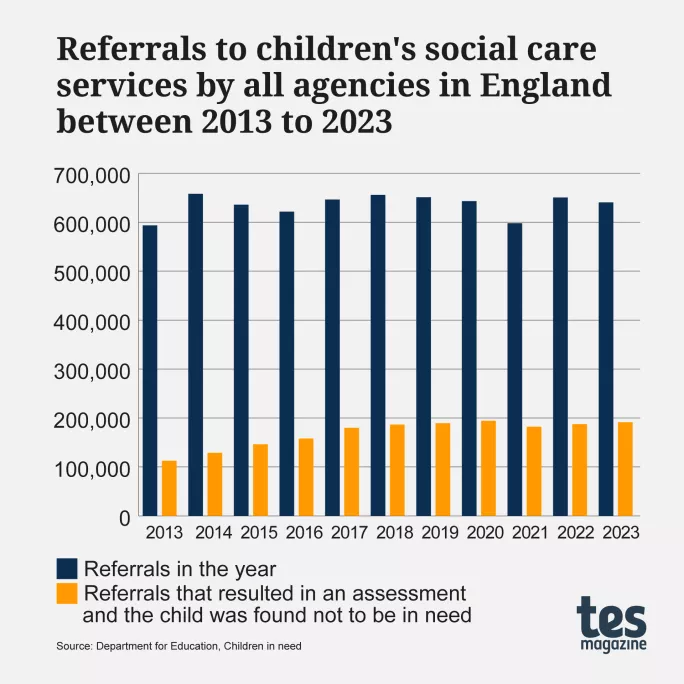

Despite this, increasingly large numbers of referrals now lead to no action being taken.

For example, DfE data shows that in 2013, 112,590 referrals resulted in an assessment but the child being found not to be in need - 19 per cent of the total referrals received from all agencies.

By 2023 this had risen to 191,460 referrals - 29.9 per cent of the 640,430 referrals from all agencies.

A far higher threshold for social services intervention is an issue that Tes revealed at the start of the year and one driven in part by ever-worsening financial situations at councils across the country, as columnist Sam Freedman noted recently.

Where’s the ‘safety net’?

The impact of stretched council finances on social care has been acute, according to John McGowan, general secretary of the Social Workers Union (SWU). His members know the dilemma that schools are facing but are too under-resourced to respond.

“What I’m hearing from members is schools are very keen for social work to be involved because it’s like a safety net, so they would rather that if there was a suspension or exclusion then headteachers have a social worker involved,” he tells Tes.

“But our profession is in a bit of crisis - there are social workers burning out fairly quickly. Caseloads are becoming more complex, and more agency staff are being used.”

These problems were made clear in a report assessing the state of social care in England by the DfE in 2022, which noted that 62 per cent of social workers felt stressed by their job, 61 per cent believed they were asked to fulfil too many roles and 59 per cent thought their workload was too high.

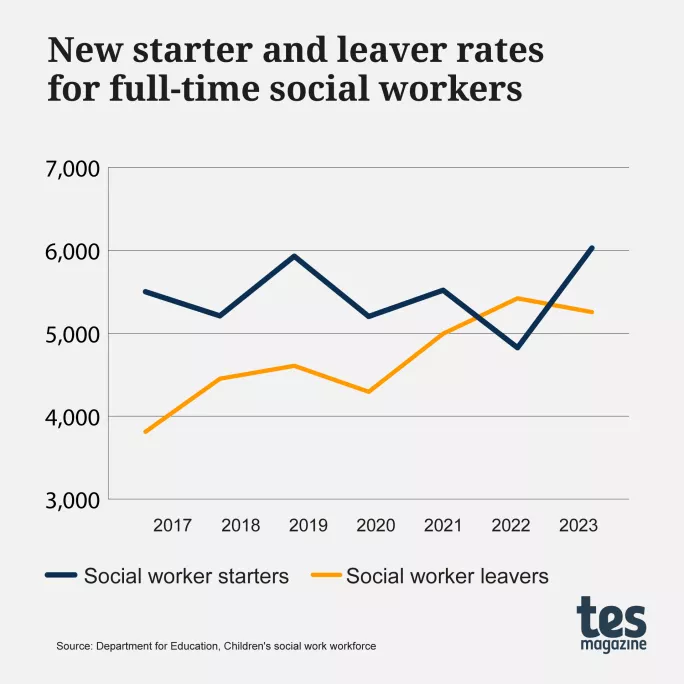

The leaving rate for children and family social workers actually passed the new starter rate in 2022, although this situation was reversed for 2023.

Meanwhile, the number of vacancies for social workers is at one of its highest points in seven years: it rose from 5,823 in 2017 to just shy of 8,000 in 2022 - although it has since dropped to 7,277 for 2023.

So where does this leave schools? For many, other options rather than exclusion or suspension are deemed the “safest” if they have fears about a child’s safety but no social care intervention is in place.

“We will risk-assess whether or not it’s appropriate to suspend because if we feel there would be an issue at home or we don’t feel that they would be safe, or not accessing education, we would internally isolate instead,” says the East of England headteacher.

The problem is that this creates “inconsistency” in behaviour policies and can cause friction with parents.

“People say, ‘Well that pupil did XYZ and didn’t get suspended, whereas this child did something similar but did get suspended,’” they explain.

A head in the South says this inconsistency factor is why schools need help: “You are torn between upholding your behaviour policy and knowing that a young person could be a risk being at home.”

And it’s not just heads facing this pressure - school governors have to be involved in exclusion decisions, too. Emma Balchin, co-chief executive of the National Governance Association, says this is becoming “emotionally exhausting” for people who are, ultimately, working as volunteers but now face “gut-wrenching” decisions about a child’s safety and life chances.

“Attempts to apply both compassion and the action outlined in the statutory guidance are getting harder. With the knowledge that the school has inadvertently become the last or only line of support, it is simply becoming a stretch too far,” she says.

Holding the line

Ultimately, some heads argue that schools can only look after what they can control.

One leader says that, regardless of external concerns, ensuring that behaviour policies remain meaningful and that a distinction between school and social care is upheld is critical.

“Without wishing to sound clinical, there is an education responsibility and there is a social care responsibility, and what happened during Covid is the lines were blurred - you had schools doing home visits, dropping off meal packages and so on - but schools are funded to educate young people.”

Mulholland, at ASCL, says this is a view that she recognises, too: “School leaders take their safeguarding responsibilities extremely seriously, and decisions to suspend pupils are never made lightly, but all schools have behaviour policies in place and will utilise these as appropriate.”

“Some children can no longer remain in school safely, forcing teachers to make impossible choices”

Williams, of the NAHT, notes that in some instances behaviour has become so bad that schools have had to act for their staff’s safety, even though they knew it may cause damage to the young person.

“Cuts to health and social care services mean some children can no longer remain in school safely, forcing teachers to make impossible choices,” he says.

Dr Jennifer Blunden, CEO of the Truro and Penwith Academy Trust (TPAT), formed of 34 schools across Cornwall, agrees that the “duty of care for staff” and the need to manage risk appropriately have to be considered.

“Schools bend over backwards to try and keep young people in our schools, but that can risk being to the detriment of the workforce and the emotional toll that takes on our teachers, leaders and support teams,” she says.

‘Something bad will happen’

Yet for some, the concern is that while behaviour management is vital, it is only a matter of time before something bad happens to a child who has been suspended or excluded into an unsafe home, and the organisation or public service that would have legal responsibility for this is unclear.

“I think the thresholds for social services support and involvement are very dangerous and I think at some point a child or children will die, and all of a sudden the story will break,” says one head.

Legal expert Smellie says that, based on conversations he has had with headteachers, he understands this fear. “I think that premonition of something bad happening is likely to be an accurate one,” he says.

Given this, he adds, and the fact that the DfE’s guidance places “sufficient levels of obligation” on heads to consider so many factors when making a decision, he can appreciate why heads may not want to issue a suspension or exclusion without external support.

“I can absolutely see [heads] are in the horns of a dilemma and I imagine most heads, if they had a genuine concern for the child’s welfare and very little confidence in any social care safety net, probably would not suspend or exclude,” he says.

In response to this, and other issues raised in this article, a Department for Education spokesperson says: “The government is very clear it backs headteachers to use suspensions and permanent exclusions to help foster calm and safe learning environments, but they must consider any underlying causes of misbehaviour first.

“To support schools in managing behaviour, we have issued updated guidance to ensure initial interventions are put in place where children are at risk of being excluded.”

Heads respond that they are already following this advice, but are still encountering the same challenges.

Support beyond the school gates

The reality for leaders is that the only thing that can alleviate these problems is better-funded social care so schools can have confidence that children will be safe when behaviour sanctions are applied. Perhaps, too, the behaviour they are witnessing could be avoided if better support was in place.

“Often if there had just been earlier intervention and some more flexibility in how we can support a family or community, rather than just how a child presents in school, we would break that cycle,” says TPAT chief Blunden.

McGowan agrees that if the social worker system was better funded and better staffed there would be more support for children outside school, which would, in turn, help the education sector.

“If we create stronger working conditions for social workers and create an environment where there’s good supervision, manageable caseloads and more funding, we can make it more attractive to recruit social workers,” he adds.

For Mulholland at ASCL, what all this shows is that what schools need most is confidence that children are safe beyond the school gates.

“There needs to be a network of support available outside of school, including adequate social care and sufficient high-quality alternative provision, to ensure that all pupils, no matter their circumstances, get the support they need,” she says.

Unfortunately, that support currently feels very distant for many, leaving school leaders facing very tough decisions around suspensions and exclusions.

For the latest education news and analysis delivered directly to your inbox every weekday morning, sign up to the Tes Daily newsletter

Register with Tes and you can read two free articles every month plus you'll have access to our range of award-winning newsletters.

Keep reading with our special offer!

You’ve reached your limit of free articles this month.

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Save your favourite articles and gift them to your colleagues

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Over 200,000 archived articles

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Save your favourite articles and gift them to your colleagues

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Over 200,000 archived articles

topics in this article