What 800,000 fewer children by 2032 means for schools

For many years there have been concerns in education about the decline in the number of pupils and how it will affect schools’ budgets and their financial viability.

Indeed, several schools are already reported to have closed as a result of this drop in numbers, which is a consequence of a fall in the birth rate.

Despite the Department for Education issuing revised data last year showing that the drop in the pupil population will not be as large as initially feared, there are still set to be 71,000 fewer pupils in schools by 2028.

Long-term drop in pupil numbers

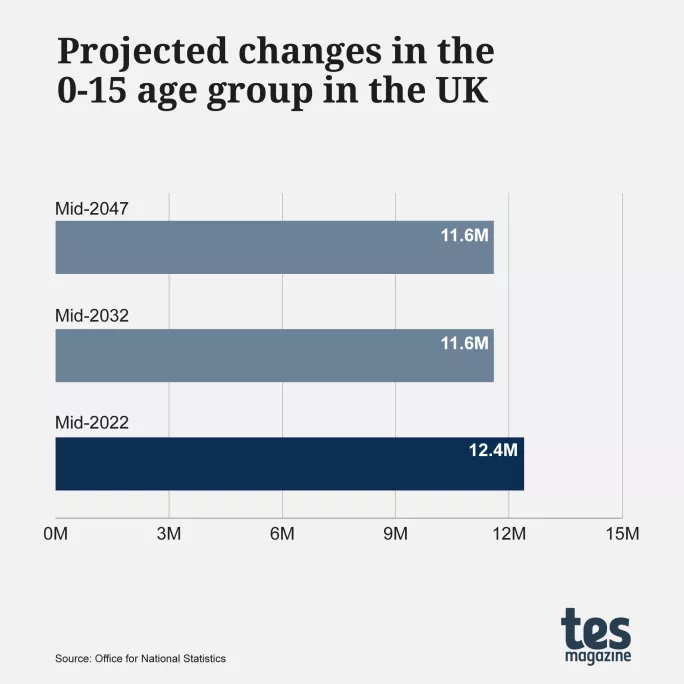

Now new data released by the Office for National Statistics (ONS) suggests this will remain an issue for many years beyond 2028, reporting that there will be as many as 800,000 fewer children aged 0-15 in the UK by 2032.

“By mid-2032 the number of children (those aged from 0 to 15 years) is projected to decrease by 797,000 (negative 6.4 per cent), from 12.4 million to 11.6 million,” the ONS says in its latest bulletin. These figures cover all of the UK, rather than just England.

Michael Scott, senior economist at the National Foundation for Educational Research, says this is a “striking forecast” and helpful for giving a “sense of direction” around what the future for the sector may look like.

“If the central forecasts come to pass, this would certainly have long-term, significant implications for education spending,” he explains.

This is because schools are chiefly funded based on the number of pupils they teach - so fewer pupils means less money. Scott says, however, that this could be an opportunity for governments, allowing them to increase per-pupil funding without increasing overall spending on education.

Leaders may be sceptical that governments will take this opportunity, though, given the current climate in which any chance to reduce public spending is being seized upon.

Of course, 2032 seems a long time away, and this may sound like a problem for the future. But with 80 per cent of the teaching workforce under the age of 50, the reality is that many working now will have to navigate the impact of this in the years to come.

Furthermore, the ONS’ crystal ball stretches as far as 2047, when it predicts that the child population will still be at 11.6 million. “This reflects the assumed fertility rates in the 2020s and 2030s being lower than those around 2001 when UK fertility was at a record low,” it explains.

- Closures and cuts: The population crisis about to hit schools

- Drop in pupil numbers: How my school became a victim of the birth rate drop

- Small schools: Small schools are on the brink. Are MATs the answer?

Now, many current teachers and leaders reading this will definitely hope that they have retired by the late 2040s.

But the fact that the pupil population appears set to remain depressed, compared with past cohort sizes, for well over 20 years shows that this is an issue that is not going away. Indeed, it may well be that current early career teachers who become the headteachers of the 2040s will still be facing this situation.

The reality now

In reality, though, as Dave Thomson, chief statistician at FFT Education Datalab, notes, the impact of population decline is already being felt as “primary schools close” and the “numbers entering secondary are beginning to fall”.

Jon Andrews, head of analysis at the Education Policy Institute, concurs, warning as well as closures, “mergers to ensure that schools remain financially viable” may also be required to offset the loss of income from a decline in pupils.

This means that if funding systems do not change, we could have tough years ahead as school closures and mergers continue to take place.

But the hope would be that by 2030, or certainly 2040, the necessary measures would have been taken to solve this problem - whether by altering funding mechanisms or reducing the size of the school estate - so that the system operates based on the reality of a smaller pupil population.

The future’s uncertain

Yet any moves to do this based on these current data projections could be risky.

Because, as the ONS points out, its data cannot account for all eventualities, such as how migration could be impacted by “recent and future policy or economic changes”. And its fertility, mortality and migration data is based on “observed demographic trends”, which, of course, could change.

For example, we may experience a baby boom in the 2030s or 2040s, or migration changes could mean more young people are in the country. So these projections could change - similar to what happened last year with the DfE’s revisions to its 2028 data.

“ONS’ population projections have been very uncertain recently,” notes Scott.

Given this, Andrews says how the ”government and the sector responds to falling rolls is inevitably going to be affected by whether those reductions are short-term or sustained” - something that is clearly tricky to predict with complete certainty.

As such, even if the current data suggests that the sector will be facing a reduced pupil population for many years to come, decisions on whether to close schools, merge them with others or amend funding mechanisms - or simply do nothing - will have to be made with the knowledge that nothing is certain.

For the latest education news and analysis delivered every weekday morning, sign up for the Tes Daily newsletter

Register with Tes and you can read two free articles every month plus you'll have access to our range of award-winning newsletters.

Keep reading with our special offer!

You’ve reached your limit of free articles this month.

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Save your favourite articles and gift them to your colleagues

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Over 200,000 archived articles

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Save your favourite articles and gift them to your colleagues

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Over 200,000 archived articles