What’s behind PE’s remarkable rise in Scotland?

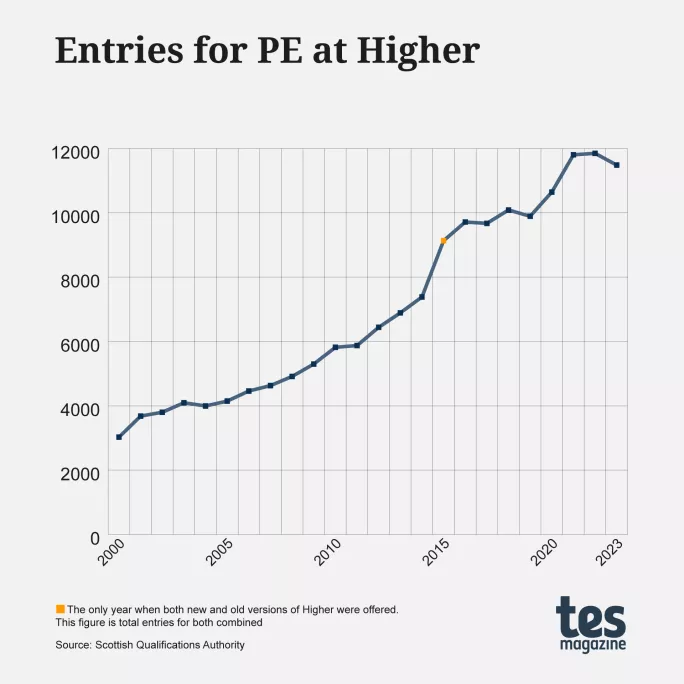

The rise of PE in Scotland in the 21st century has been remarkable. In 2000 there were 3,028 Higher entries - by 2022 that had almost quadrupled to 11,850.

PE has also become emblematic of a fundamental change in how subjects are viewed in Scottish schools more generally, of a move away from old hierarchies and preconceptions - and from the reductive pigeonholing of certain subjects, including PE.

In Scottish Qualifications Authority statistics for 2000, the subjects on offer were not listed alphabetically like they are in SQA spreadsheets now. Instead - with one notable exception - they were largely bunched together with subjects deemed similar in some way.

First came the languages. Then the numeracy subjects (just two: maths and accounting and finance). Sciences were next, then a mix of broadly social and philosophical subjects. The biggest and most eclectic group (from tourism to technological studies, from mechatronics to mental health care) could be described as technical and vocational subjects, before we reached the arts.

Then, sitting on its own if you scrolled down far enough, PE appeared as a singular subject, hanging on grimly to the bottom of the list - apt symbolism for a subject that was an awkward fit when schools in Scotland and beyond were more resolutely focused on studies deemed “academic”.

How the perception of PE has changed

Think of PE teachers’ depictions in popular culture, as custodians of a subject that was isolated and a law unto itself: Brian Glover in Kes being more interested in fuelling his own ego than teaching anything; Jake D’Arcy in Gregory’s Girl being belittled by his colleagues; the PE department ogres of Grange Hill preying upon the weakness of non-sporty pupils.

However accurate those portrayals were, they reflected a common view that PE sat apart - for better and worse - from other parts of the curriculum, a distinct chunk of the school week that some pupils relished and others dreaded.

The change since then has been dramatic, both in raw statistics and in how PE is perceived.

In 2000 PE was the 12th most popular Higher; now it has the most entries of any subject apart from English and maths. That rise has a number of explanations, believes Dominic Tollan, editor of the Scottish Association of Teachers of Physical Education (SATPE) Journal.

Tollan says more space and opportunities have emerged for PE in recent years with the establishment of interdisciplinary and cross-curricular learning as a priority for Scottish schools. And the wide scope of the S1-3 Broad General Education has created room for PE to showcase its distinct strengths in the early part of secondary school, he believes.

The “interaction and competitiveness” and “dynamic environment” of PE have always been a draw for certain students; there is also the appeal of securing a Higher that, while based on rigorous study, as with any qualification at that level, is perceived as different to more “academic” subjects.

Tollan - who spoke to me at the first full in-person SATPE annual conference since before Covid, held at Larbert High School in September - says that growth at Higher level has also been fuelled by many students taking it in S6, to try something different and expand the range of subjects they studied in S5.

The knowledge that PE now offers far more than the pursuit of traditional sports - with the subject’s embrace of data analysis and sports science - has widened its appeal. PE now attracts many students beyond the aspiring sports stars and next generation of PE teachers.

PE teachers have been some of most thoughtful and resourceful teachers I have met, constantly thinking about how their subject can adapt to changes in education more broadly. The hard-nosed “drillie” of bygone PE departments - often feared by pupils, often disparaged by other staff as not a “proper” teacher - is an increasingly redundant stereotype.

“There used to be that rigid perception of PE - the ‘drillie’ kind of concept - but I think we’ve run away from that,” says Tollan. He is mindful, however, that the balance must not tip too far another way - that while a more theoretical approach to PE is to be broadly welcomed, the “physical” in physical education must never become an afterthought.

- Physical education: Is PE the most important school subject of all?

- Primary PE: Four ways to improve PE in Scottish primary schools

- Active education: Teachers told to get pupils “up out of their seats” to learn

- England: PE “enjoyment gap” for girls is widening, new study warns

Also at the SATPE conference was Theresa Campbell, a former senior lecturer in PE at the University of Glasgow and leader of the Scottish Primary Physical Education Project that ran from 2006 to 2012.

Campbell started her career as a primary teacher in Scotland in the early 1980s, a time when, she recalls, many pupils did not enjoy PE and felt excluded or uncomfortable - she even used to see pupils with disabilities sitting on the sidelines, saying they were not allowed to take part.

She is delighted that PE is now thriving as a much more inclusive subject. She cautions, however, that - “because it was definitely a Cinderella subject” in the past - there has at times been a tendency “try to justify itself as an academic subject”. That becomes problematic, says Campbell, if this clouds what makes PE “special” in the first place.

“It’s keeping the ‘physical’ in physical education, but also keeping the ‘education’ in physical education - that we’re not just making [pupils] run about,” she says. “That they’re also able to understand what they’re doing and why they’re doing it - and having fun while they’re doing it.”

Tollan says PE offers all sorts of interdisciplinary learning - if you’re taking notes on a football match, that’s literacy; if you’re timekeeping or analysing basketball shots, that’s numeracy - but that this works best when it is “natural, organic in the lesson” and classes are “academic, without pushing the academic overly”.

“There used to be that rigid perception of PE - the ‘drillie’ kind of concept - but I think we’ve run away from that”

Tollan, who is also SATPE’s rep for the primary school sector, still sees room for a lot of improvement in PE.

In 2011 the Scottish government announced that by 2014 every primary pupil would get at least two hours of PE a week (while S1-4 students would be guaranteed two periods, typically 100 minutes). Yet Tollan stresses that that entitlement only achieves so much when there is still a lack of confidence and expertise among many primary staff. He still regularly encounters the “shortsighted” view in primary schools that PE is simply about “making them run about all the time”.

Primary schools do not have enough support with PE, Tollan believes, and he is in discussions with Education Scotland about this could be improved. With the “massive uptake” of PE students at Higher these days, he stresses, “we need to make sure that when they’re getting to that phase they’re ready for it”.

The Covid pandemic both helped and hindered PE, says Tollan. On the one hand, the social interaction of PE and the impetus it provided to get up from behind a desk made it attractive at a time when pupils were “yearning for fun, for play, for engagement with one another”.

On the other hand, social and fundamental movement skills - running, jumping, throwing, catching - took a hit. PE staff have been taken aback at a lack of the basics, such as S1s struggling to hit a shuttlecock over the net; staff having to step in to help with simple catching games; pupils who were being considered for netball and basketball teams before Covid seeming lost after the lockdowns - “It was almost like they were looking at each other, going, ‘What do we do?’”

Inventive ways to engage pupils

Tollan has been disappointed by some local authority guidance on emerging from Covid that has focused on children’s mental health but said nothing about physical health - a sign, in his view, that PE still has much work to do.

You can count on the inventiveness of PE teachers, however, he believes. Sometimes, engaging pupils is all about presentation - so don’t label it “dance”, label it “movement”, and play “tig games” that boost core skills rather than using offputting jargon like “core skills”.

One of Tollan’s biggest successes has been firing up the enthusiasm of challenging groups of P4-5s after the lockdowns.

Many had decided that, for whatever reason, sport was not for them, so Tollan steered sessions away from traditional organised sports. Instead, he went to B&M and bought a whole load of those two-metre foam “noodles” you get in swimming pools - so that he could start a course on lightsaber battles.

To begin with, Tollan’s pupils got excited as they “thought they’re going to batter lumps out of each other”; instead they choregraphed jumps, rolls and entire sophisticated routines. Without the D word ever being used, they had enjoyed a series of dance classes.

In a time of broadening curricula and priorities, subjects and activities that used to orbit far from the main business of school life have seen their status grow markedly. In Scotland in 2023, certainly, the force is with PE.

Henry Hepburn is Scotland editor at Tes. He tweets @Henry_Hepburn

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

topics in this article