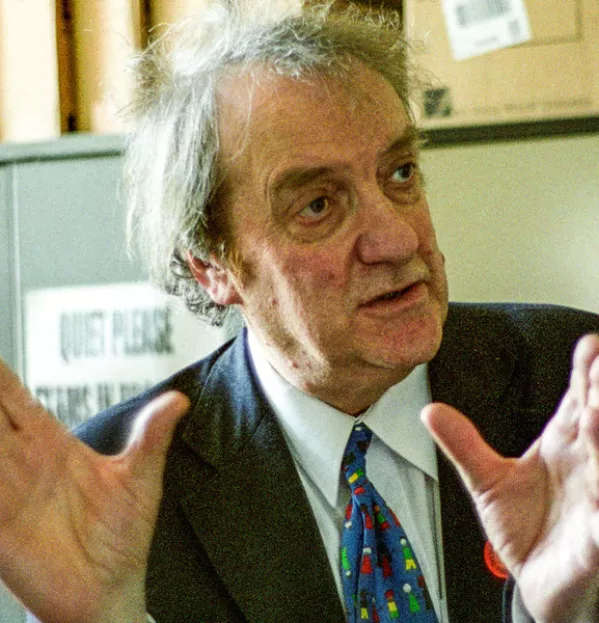

‘Sir Tim Brighouse loved, cherished and respected teachers’

Sir Tim Brighouse was unique. He was a genuinely brilliant educationalist who thought deeply about schools’ policy, and yet he was also beloved of the hundreds of thousands of teachers that his career touched. He managed to balance the politics and the practical and, as a result, he was an extraordinary figure in the public life of this country.

I consider myself incredibly lucky to have known him - and to have learned from his wisdom - over the past 15 years. His understanding of the education system was hugely impressive, but it was his way of working that set him apart. It was predicated on something all too unusual among many public servants: he loved, respected and cherished classroom teachers.

The core of his philosophy was that if we could motivate teachers to have confidence in themselves and their professional knowledge - and then to share that insight with as many other teachers as possible in semi-formal and formal professional dialogue - we would lift the whole system.

Some of Sir Tim’s interviews and articles for Tes

- Tim Brighouse: my 13-point plan for school improvement

- Are you ready to be a headteacher?

- Have 10 years of a knowledge-rich curriculum helped pupils?

- Tim Brighouse’s nine ways to minimise exclusions

Sir Tim Brighouse in Birmingham

I remember him telling me with a high degree of confidence that in every single classroom in the country, something innovative was happening. If only, he pointed out, we could somehow surface and share each and every example of professional brilliance, from the smallest to the biggest, think of the power that would have.

This was the grounding for his way of working with schools.

I remember him reminiscing about his time in Birmingham, where he had been chief education officer during the early 1990s. Tim explained there were a number of underperforming schools at the time. He visited each and every one of them. And, ahead of each visit, he would ask his officers to identify one brilliant thing that the school was doing.

“I’ve come to see your school because I hear you’re doing wonderful things with X,” he’d start these potentially difficult meetings. The positive results would soon follow.

It is said - and I have no reason to doubt this - that during this time, Tim personally wrote to every single teacher joining a school in the Birmingham local authority to welcome them.

The London Challenge

Over the course of his career, Tim’s reputation grew and grew, despite the best efforts of certain Conservative politicians to tarnish it.

Under Tony Blair, he was appointed to lead the London Challenge, a singularly vast school improvement project that aimed to lift the results of schools throughout the capital.

He set about this initiative with his usual zeal: his vision was to bring schools in similar circumstances, wherever they were located, together to learn from one another and to work out shared strategies for improvement. He was also determined to avoid any stigmatising language about failure.

There was, of course, a lot more to the London Challenge than that, but that was the core of the idea.

Today, London has one of the very best state school systems in the world. There is a neverending debate about why and how this has happened, and many are keen to point out that the advantages the capital enjoyed (demographics, funding, young and enthusiastic teachers) rendered the improvement we have witnessed inevitable.

But ask any head who was around at the time to explain this step-change in improvement, and Tim’s name will be among the first things that come out of their mouths. School leaders and teachers simply loved working with him.

Labour and education

Tim was a deeply charismatic human being (in a weird, peculiarly English way), and yet he somehow managed to combine that with being down to earth. His educational philosophy was at once both highly idealistic and grounded in common sense. Embodying these two apparent contradictions was his great achievement.

In Tim’s personal mission, his life’s work, his moral compass and his pragmatism, we can see a model for rebuilding the confidence of this country’s education system as it recovers from the pandemic, austerity and the recent years of maladministration.

Tim was, discreetly, a Labour man to his core. An incoming Labour government could do a lot worse than learning from his approach to public service and public administration.

Tim believed in a confident, high-performing state as a way to bring about long-term social change - and he believed in caring for, and respecting, those who choose to provide this service in the classroom.

This country - not just its teachers - needs more people like Tim Brighouse.

Ed Dorrell is a partner at Public First

topics in this article