- Home

- Teaching & Learning

- General

- What works to get children reading for pleasure

What works to get children reading for pleasure

This article was originally published on 7 March 2024.

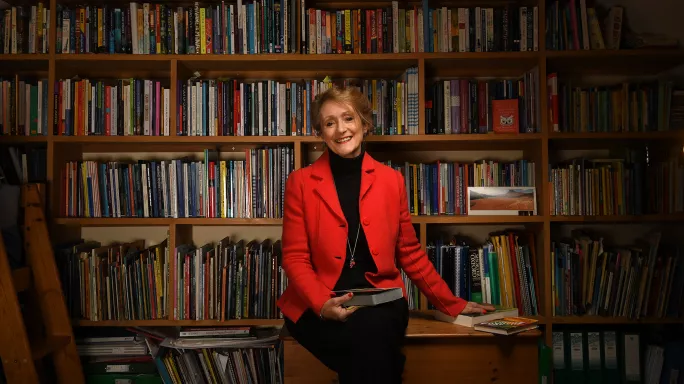

When it comes to supporting reading for pleasure, Professor Teresa Cremin says that England is “in a very worrying place”.

According to the latest UK statistics from the National Literacy Trust (NLT), fewer than half (43 per cent) of children and young people aged 8-18 say they enjoy reading in their free time - the lowest figure since the survey began in 2005.

“And it’s not only the NLT data,” Cremin points out, “it’s also the international data for England in the latest Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (Pirls) from 2021”.

Pirls surveys 400,000 9- and 10-year-olds in 57 countries around the world every five years, and the latest study shows that England is “on a significant downturn, with far fewer children reporting loving reading than their peers internationally,” Cremin says.

Just 29 per cent of children in England said they enjoyed reading, compared with 46 per cent of children internationally. “That’s not even a half, which is a worry in itself, but we’re under a third and that’s a real concern,” she explains. “And those numbers have been dropping over time, down from previous surveys.”

All of this is particularly troubling to Cremin because she has devoted her career to researching the benefits of reading for pleasure and supporting schools to implement best practice in this area.

A former primary teacher, she is now professor of education (literacy) and co-director of the Literacy and Social Justice Centre at The Open University, where she also leads a reading for pleasure research and practice coalition.

Over the years, she has been called upon to advise the Department for Education on reading for pleasure, as well as previously taking the roles of president of the UK Reading Association and the UK Literacy Association.

Cremin’s latest project involved developing a practical framework to support schools in promoting not just reading for pleasure but also “writing for pleasure” - an area she feels has been under-represented in both policy and research.

Tes speaks to her about the recommendations of the new framework and her research more broadly.

We all know that reading is important, but what does the research say about why we should be encouraging children to read for pleasure, specifically?

The research tells us that reading for pleasure is associated with lots of benefits: academic, social and emotional - for example, cognitive development, reading comprehension, vocabulary and writing.

We know that there are wellbeing advantages, too. There have been many studies in the past six to eight years highlighting the association between being a reader and lower levels of emotional problems and better prosocial behaviour, but this still isn’t as widely known as perhaps we would wish it to be.

The International Literacy Association argues that it’s every child’s basic human right to read for pleasure. And Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development research found that being a frequent reader is more of an advantage than having well-educated parents, in terms of outcomes.

So, reading for pleasure is arguably a matter of social justice because it can mediate the effects of all sorts of things, including gender and socioeconomic status.

Recent statistics show that reading for pleasure is on the decline among young people in England. Why do you think this is happening?

I think technology is an influence, but I also think we don’t see any kind of modelling of reading in the media. Reading to and with your children is absent on television, for example.

We’re not getting close enough to what young people want to read, either. Are we talking to them about the kinds of text they are interested in and introducing them to a wide range? Or are we expecting them to read the “good texts” of today, or indeed of yesterday?

In my view, we don’t give enough weight to where the youngsters are coming from and what they’re genuinely interested in reading.

In many research studies I’ve been involved in, we’ve seen that when teachers listen more closely, look more closely and involve young people, it becomes a journey of their own. It is the children’s reading journey, not the journey the teachers want the children to take.

Their rights as readers should be exerted rather than the wishes of the teacher or the parent.

Reading for pleasure is already a priority for most schools, but your latest project also looks at encouraging “writing for pleasure”. Why do you think this is an area worth focusing on?

As a society, I think we view reading and being a reader as an accepted norm, whereas there’s far less cognisance of writing and being a writer. The concept of “writing for pleasure” isn’t common; it doesn’t really exist in research or policy.

Reading for pleasure has been mandated in England since 2014, but “writing for pleasure” isn’t a term that’s used at all within the national curriculum in this country, or in any others that I know. Instead, it’s more often about “creative writing” or “composition”.

Why is that distinction important?

A while back, I did a systematic review with [researcher] Lucy Oliver and we found that teachers can have quite narrow conceptions of what counts as “writing”; they presume that being a writer involves creating poetry or a novel. And if we have that narrow view of writing, then people won’t see themselves that way.

Are you writing song lyrics on a Saturday afternoon? Are you writing a play script? Probably not, but you will be communicating through written communication and that is writing.

So, there’s a real challenge, I think, for teachers to take up that position of being a writer, of seeing themselves as being inside the writing process, rather than being alongside children as the educator, which is a very different position to be in.

You recently published a practical framework to help schools overcome some of the challenges around supporting reading and writing for pleasure. Can you tell us about that?

Yes, Reading and Writing for Pleasure: A Framework for Practice was published in December 2023.

The Mercers’ Company [a charitable foundation] was putting together a three-year study that focused on reading and writing for pleasure, and we applied to be its research partner. It saw reading and writing as a national concern, and identified six organisations running programmes already, nurturing children as readers or writers, mostly one or the other.

Our job was first to review the international research literature around reading and writing for pleasure, and combine those to explore what the evidence says, and what approaches and methodologies seem to be most effective in inspiring young readers and writers. Then we looked at the programmes, what they offer and how they undertake their practices. We weren’t asked to evaluate their success, but we did do fabulous, fascinating focus groups with the kids.

Finally, we synthesised the two sets of understanding, the literature, and the data from the programmes, to develop a research-informed framework for practice.

And what did you find?

We weren’t sure that there was necessarily going to be a synergy between the six programmes, but actually, there were some very interesting and common connections between them, particularly in the ways they formed relationships with the children and gave them agency.

We saw that the young people in the programmes were positioned as readers and writers, not children “doing” reading and writing, which is a really different identity position. They were respected and listened to, and their choices were honoured, and, as a result, we saw that they stood up as readers and writers with something to say.

There’s quite a lot of research evidence that shows the significance of self-efficacy predicting attitudes, which, in turn, can also predict the frequency with which we engage as readers and writers recreationally. It’s a case of: “I feel good about myself as a reader or writer, and I like it enough to do more of it.”

What was special about how the programmes formed relationships with pupils?

Informality is key. It’s about reshaping the interface between teachers and pupils, so the relationship can be non-hierarchical: not pupil to teacher, but reader to reader. You’ve both read the book and both thought it was a bit scary, and you’re chatting about it, with mutual respect and reciprocity and authenticity.

Good practice is about being really personally involved, mediating and motivating pupils’ engagement, but also being highly attuned to them as individuals. There are plenty of research studies that show that such connections make a difference in young people’s engagement as readers or writers.

They care about what their teacher thinks, even if that’s something quite different from them, because you can have a discussion about it. That bond is built over many shared texts, which is why teachers need to read the books, so they can discuss them in a meaningful and deep way with young people rather than offering a surface commentary.

The framework recommends that teachers also “explore and potentially broaden their conceptions of literacy and reader and writer identities”. What does that look like in practice?

Teachers in the research studies that we read, and the research studies I’ve led - and certainly those teachers in this last piece of Mercers’ work - had broad, expansive conceptions of reading and writing, and saw their work as the development of readers and writers whose views, ideas and rights should be upheld.

I think it’s to do with reflecting on the nature of reading and writing, and becoming more conscious. If you’re working in a school education system, it’s almost inevitable that you’ll have a narrower conception of what reading and writing are and what they’re good for, and what counts as reading and writing because, arguably, it is partly framed for you by the school curriculum.

In our Teachers as Readers study, we helped teachers reflect on the different habits they had. Some of them would read the end of the book before they had finished reading the rest, and others were appalled by that. Some in the group said they would skip the descriptive bits because they didn’t find them interesting, and others would read every word.

It began to register that we’re all just different as readers, we’re not right and wrong. We’ve developed our own habits and we have the right to do so. The teachers were beginning to be more conscious of themselves as readers, and reflecting on reading and what it is to be a reader helps teachers to engage as genuine readers in the classroom.

When that happens, reading isn’t just a school activity but has a higher degree of authenticity and engagement, and that wider conception more effectively motivates children because they’re developing as readers in the real world, not readers for schooling.

Another recommendation of the framework is to embed “opportunities for relaxed and supportive social interaction” around reading and writing for pleasure. Why is that important?

We found that social approaches made a big difference. You can centre stuff around children’s ideas for writing and reading, and give them choice, while also providing peer support and playful activities and opportunities to interact with one another. That way, reading isn’t a solo activity, nor is writing. It doesn’t mean you have to do shared writing, but you can share the writing you’re doing.

Too often, in the classroom, reading and writing are conceived of as individual cognitive activities, but some of the characteristics we want to develop are around interacting with others as readers and writers, sharing with others, listening to others, and adults and peers giving good feedback on others’ writing because they enjoyed listening.

We saw that really strongly in the different programmes: a great sense of sociability, interaction and conversation, in a low-key, informal way. Lots of noise and lots of people talking and sharing and swapping and moving to somebody else. That was motivating. You can be socially motivated as a reader or writer, and I think we underestimate that in schools.

Peers are hugely valuable, too; if you can build a community of writers and readers, then you’ve got that social support network, that sense of a collective experience and an interactive relationship.

It’s not a solo experience. That’s really key. And if teachers could do more of that, the research evidence shows us they would make more of a difference.