Wales’ Pisa results have ‘an air of inevitability’

There is an air of inevitability about this week’s Pisa 2022 results, particularly in Wales where pupil performance in the international tests continues to fall well short of expectation.

A frenzy of media interest lights the touchpaper for political dissidence; schools and their teachers are, as ever, caught in the crossfire of the Programme for International Student Assessment (to give its full, unwieldy name).

It is all depressingly predictable and Wales’ place at the foot of the UK league table has become something of a surety.

Granted, a drop in 2022 Pisa scores was no surprise, given the vast majority of participating countries and member states went backwards, owing at least in part to Covid-19.

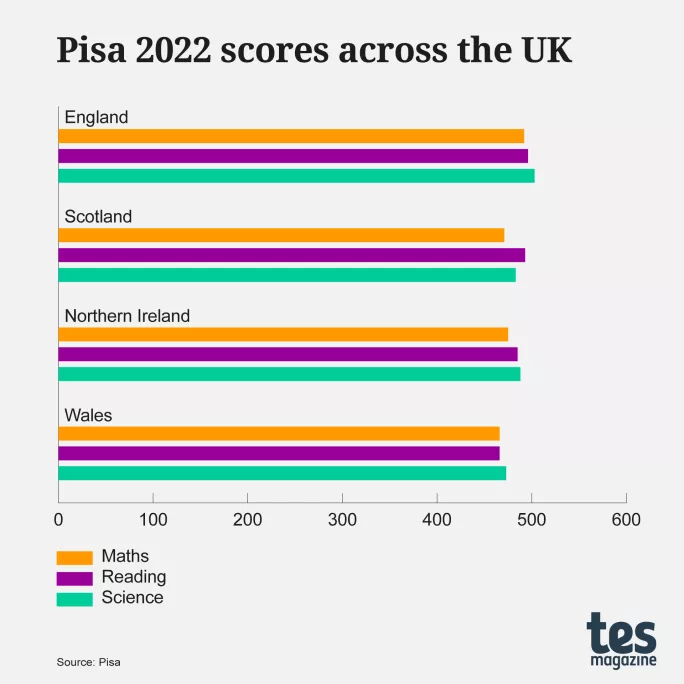

The difficulty for Wales is that its decline was strikingly steeper than those registered in England, Scotland and Northern Ireland (and it was already starting from a much lower base).

Welsh scores went down by 21 points in maths, 17 points in reading and 15 points in science, after a mini-revival in 2018 when modest improvements against all three measures were recorded.

International comparisons are, broadly speaking, fraught with danger and Pisa does not compensate for cultural difference.

But comparing the home nations (and the Republic of Ireland, whose scores held up noticeably well) is a much more reliable exercise. That Wales has dropped even further behind, having trailed its near neighbours in each of the last six Pisa rounds, is cause for concern.

It will be some time before the dust settles and Pisa results in their entirety (including the often overlooked pupil and headteacher questionnaire data) can be properly digested, but that does not preclude early observations.

My first relates to the well-worn “Covid excuse” for poor performance. Ministers in Wales were quick to blame the pandemic for its Pisa plight, and while there is little doubt that repeated lockdowns and lost learning impacted significantly on pupil progress through Covid, it does not account for Wales’ trend over time, nor the rest of the UK’s comparatively better outcomes.

Pisa supremo Andreas Schleicher makes this abundantly clear in his Pisa Insights and Interpretations report, noting that “educational trajectories were negative well before the pandemic hit” and that “long-term issues in education systems” contributed to the widespread drop in performance.

So Covid was a factor, but not the only factor.

Which begs the obvious question - what else has been going wrong in Wales?

- Related: UK’s Pisa scores fall in maths, science and reading

- News: Scotland’s Pisa scores drop across the board

- Jeremy Miles: ‘We will use every lever to support Welsh schools’

- School attendance: Welsh schools told ‘make learning interesting’ to cut absence

There has been much criticism on social media, in the early aftermath of Pisa results, of Wales’ developing purpose-led curriculum.

Comparisons with Scotland, whose scores have been on a steady downward trajectory for some time, were inevitable and not without justification, given its Curriculum for Excellence provided inspiration for the fledgling new Curriculum for Wales (CfW).

Let’s be clear, Wales’ 2022 Pisa scores are in no way a reflection of the current reform agenda; the pupils who sat Pisa tests late last year had not been exposed to new arrangements and it will be several years before CfW plays out in results.

Nevertheless, Scotland’s downturn poses awkward questions for Wales and the Welsh government, which appears steadfast in its commitment to seeing through what has been described by ministers as “biggest set of education reforms anywhere in the UK for over half a century”.

This, I think, is a sensible approach; teachers in Wales have been through enough and are understandably tired of the government’s tendency to change direction at the first hint of adversity. There is only so much policy churn one can take before losing heart and hunkering down.

That does not mean, however, that we should pass Pisa off as “just another measure”, as has been argued several times already this week.

Yes, Pisa only provides a snapshot; yes, Pisa doesn’t assess everything we value; and yes, Pisa is methodologically flawed.

But what Pisa does measure is important; it’s important to our reputation, to our economy and most of all, the life chances of our children and young people. To ignore its key findings would be irresponsible and do them a grave disservice.

Pisa scores reaffirm a chink in the armour

Indeed, it could be argued that Pisa merely reaffirms that which we knew already - that basic skills in Wales are, on the whole, substandard and some way below where they should be.

This in itself is an important point, with Wales’ inspectorate Estyn having long since bemoaned deficiencies in reading and maths; Wales’ GCSE and A-level outcomes being consistently below those in England and Northern Ireland; and personalised assessment data revealing a drop in standards of reading and numeracy across the primary and secondary age range.

The unveiling of a new national plan “to drive forward improvement in maths and literacy”, a week before Pisa results were published, is not coincidental.

The Welsh government has identified what it perceives as a chink in its armour, only this particular chink is in danger of becoming a chasm. Quite how Wales has ended up in this position, a decade after the launch of a national Literacy and Numeracy Framework (introduced, ironically, after another Pisa crisis), is not immediately clear.

This brings me neatly onto another frustration, relating to the way in which Pisa has been used by ruling politicians to rationalise the decisions they have taken.

Those of us who have been around long enough will remember well the profound impact of the 2009 Pisa results on Wales’ education system; the ink had barely dried on a raft of sweeping changes when momentum shifted again, with Pisa 2012 inspiring a new approach to curriculum and assessment.

The mood music coming out of Cathays Park suggests there will be no such volte-face this time.

That to me is a good thing, albeit the Welsh government must be willing to accept scrutiny and constructive challenge whatever its results.

In the same way ministers would be advised to resist ratcheting up Pisa rhetoric when it suits them (Wales being one of a long list of countries to have used Pisa “shocks” to justify whole-system change), so too must they refrain from playing down Pisa’s significance when it is not convenient (like when the system is already part-way through an extensive reform programme).

The Welsh government’s uneasy and somewhat volatile relationship with the international tests should be carefully considered, and a healthy debate on our future involvement in - and aspirations for - Pisa would be no bad thing.

We must be resolute, not reactionary - and base our response to Pisa on a more rounded evaluation of our education system; in short, we must avoid being the architects of our own downfall.

Wales’ Pisa scores: what should happen next?

What matters now in Wales is what happens next. Education minister Jeremy Miles has resolved to bring education leaders “together around the table” in January to reflect on Pisa and develop “a shared and comprehensive response to this challenge”.

This to me feels like a fork in the road and an opportune time to pause and take stock; to reflect, review and evaluate what we have done, where we are and where we’re going.

It is not time to throw babies out with bathwater - too much positive energy, goodwill and determination has been expended to flip-flop yet again in response to something, deep down, most of us could foresee.

Wales must be prepared to ask itself some difficult questions, starting with what is missing from the reform agenda? Where are the gaps and is there anything we need to take out or adjust to better prepare our youngsters for an increasingly competitive world?

We must be honest about what is manageable in a complex and unsettled educational landscape, still grappling with the full effects of the pandemic and a near-constant flow of national guidance.

We need to look again at what we prioritise, and what we are prepared to let lie (the Welsh government’s plan to change the school year is I think symptomatic of a much deeper problem).

What this means for Wales is uncertain, though I anticipate more a tinkering around the edges than wholesale policy overhaul; any remedial action must be taken with the profession in mind.

We cannot, under any circumstances, expect teachers and leaders in Wales to ”do more” and “push even harder” to narrow the Pisa gap; funding cuts and teacher redundancies are already biting hard and the toolbox is bare.

It is a perfect storm of poor results, heightened pressure to perform and a chronic lack of resources; if there is a tipping point, then it isn’t far away.

We know that teachers make the biggest difference, and that everything else works back from there. So let’s start by focusing on what really matters.

Dr Gareth Evans is director of education policy at the University of Wales, Trinity Saint David. He tweets @garethdjevans

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

topics in this article