Attendance: How England compares with the rest of the world

Today the results of the 2023 Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (Timss) have been published.

The study, carried out by the International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement, is the longest-running large-scale international assessment of maths and science, based on tests sat by pupils in 59 countries at ages 9-10 (Year 5 in England) and ages 13-14 (Year 9).

The headline finding is that England’s primary maths scores have dropped for the first time but its science scores have increased significantly.

But alongside the academic data, Timss also includes interesting contextual data from the participating pupils that is worth examining, including on absence.

Timss data on pupil absence

Overall in England, a total of 8,330 pupils in 267 schools completed the four Timss assessments in 2023, when the data was on: Year 5 and Year 9 maths, and Year 5 and Year 9 science.

As part of the completion of each test, pupils were asked how often they were absent from school, with the choice of answers being once a week, once every two weeks, once a month, once every two months, never or almost never.

For this analysis, we will focus on the most concerning categories of respondents: those who chose once every two weeks - which is aligned with the government’s definition of persistent absence meaning missing 10 per cent of school - and once a week.

This Timss data is, of course, not as comprehensive as the official government data on attendance but it does offer the chance for some interesting international comparisons between England and selected other nations (see below). If you want to see data for all nations in Timss you can find it here.

Year 5: Absent once every two weeks

In total, 4 per cent of pupils in England who sat the Year 5 mathematics and science assessments said they were absent once a fortnight.

This places the country joint fourth, or in the top 11 of the 65 participating nations (the higher the ranking, the better the attendance) - with the same rate of persistent absence as Albania, Cyprus and the Netherlands.

France, Spain and Portugal (all in joint third place) did a little better, with 3 per cent of pupils saying they were absent, while Germany (in joint fifth) fared worse at 5 per cent.

All the highest achievers - with 2 per cent or less - were Asian nations, including Taiwan, Japan and South Korea.

Spare a thought for parents in the Slovak Republic, Saudi Arabia and Kuwait, though, as they were right at the bottom of the table, with 14 per cent, 13 per cent and 11 per cent of pupils reporting absence once a fortnight respectively.

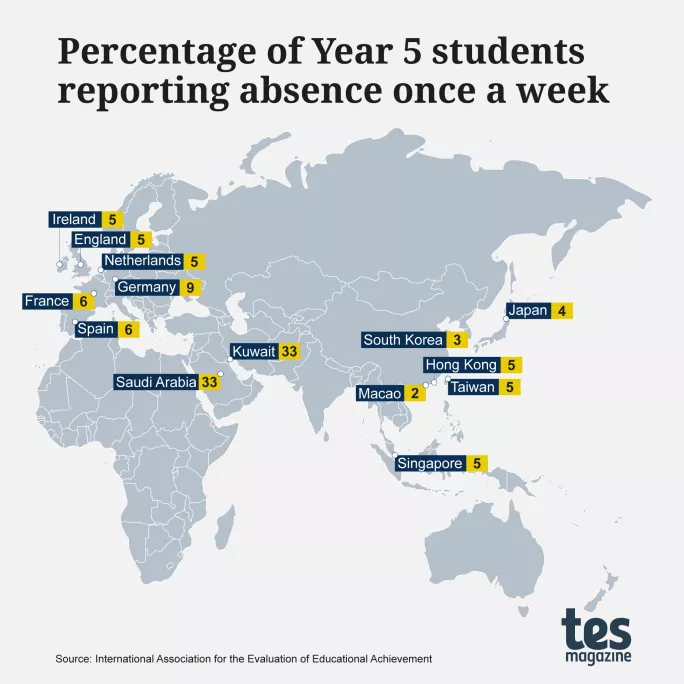

Year 5: Absent once a week

At the most worrying end of the scale - those pupils who reported themselves absent once a week - England’s proportion of Year 5s was slightly worse, at 5 per cent.

While this is clearly concerning, within an international context it actually puts England higher up the table, within the top nine countries and in joint fourth place, alongside the Netherlands, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Ireland and Singapore.

Top of the tree were Japan, South Korea and Macao, with 4 per cent, 3 per cent and 2 per cent absence rates respectively.

This time both France and Spain (joint fifth place) fared just a little worse, at 6 per cent. Germany (joint seventh) had 9 per cent of pupils absent once a week. Saudi Arabia and Kuwait fared worst with alarming rates of 33 per cent.

More on school attendance:

- Unauthorised absence rising but attendance has improved

- Pupil absence: new regulations on fines

- Why regulating the holiday market would help schools

Year 9: Absent once every two weeks

Moving to the older students, a staggering 10 per cent of the Year 9s who sat Timss in England said they were absent once every two weeks.

This placed England in the top 16 of the 50 nations in the Year 9 tests, at joint-eighth position alongside Austria, Azerbaijan, Hungary, Kazakhstan and the United Arab Emirates.

France (sixth place) did a little better with 8 per cent, and Portugal (joint third) fared much better with 4 per cent. No comparison can be made with Germany, as it did not take part in the Year 9 assessments.

The same nations topped the table once again: South Korea with 1 per cent, then Japan, Hong Kong and Taiwan, each with 2 per cent.

Meanwhile, the countries with the highest rates at this level were the Czech Republic, Georgia, Kuwait and Saudi Arabia, with 18 per cent of students in these countries reporting themselves absent once every two weeks.

A surprise in this category is Finland: the country that many education policy experts look up to had 17 per cent of children reporting absence once every two weeks, placing the nation 46th out of 50.

Sweden - another Scandinavian country whose education system is admired by many - also performed poorly here, at 14 per cent.

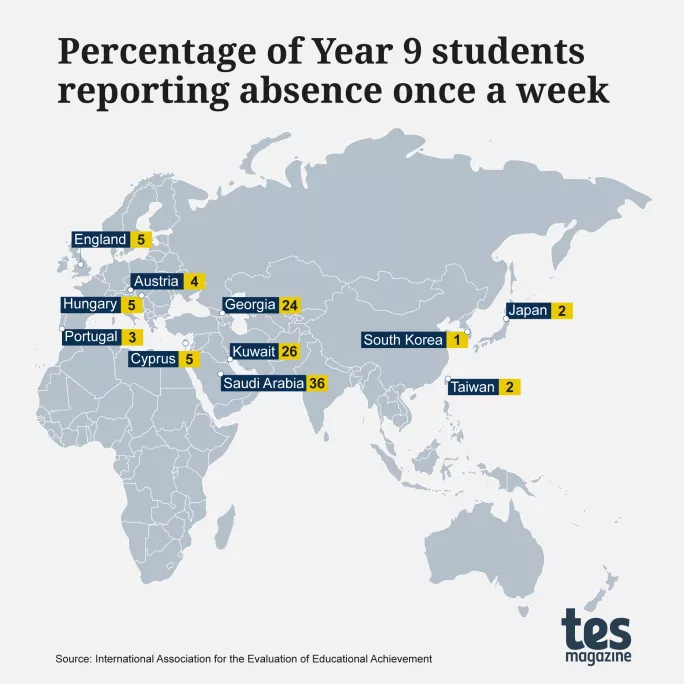

Year 9: absent once a week

And finally, we come to the Year 9 students who reported themselves absent once a week.

In this category, England scored 5 per cent - in line with this frequency of absence for Year 5s.

This made for an improved league table position in the top nine countries, joint fifth alongside Cyprus and Hungary.

Portugal (third), and Austria (fourth) fared better with 3 and 4 per cent each, while, once again, South Korea topped the table with 1 per cent, and Japan and Taiwan followed with 2 per cent.

The most worrying figure was, again, in Saudi Arabia, where more than a third of students sitting this test reported being absent once a week. Kuwait with 26 per cent and Georgia with 24 per cent also performed poorly.

What does this all mean?

We know absenteeism is a major problem in England, particularly following the pandemic.

But in some ways the Timss data shows that, compared with many other nations, England is doing reasonably well. However, there is clearly more to do - as is the case for many other countries, including European rivals.

And, once again, it seems that if lessons are to be learned, policymakers will need to turn their attention to Asian nations.

Responding to the findings, Pepe Di’Iasio, general secretary of the Association of School and College Leaders, tells Tes that England’s ranking is “encouraging”, adding: “We suspect that many countries are facing similar challenges following the impact of the pandemic.

“International comparisons can be helpful to see what is working successfully in other countries and what lessons we can learn from one another.”

However, he warns that attendance “cannot just be left for schools to solve on their own”. It requires families to be able to access support, such as to mental health services, that is properly funded.

Chris Paterson, co-CEO at the Education Endowment Foundation, agrees that it could be helpful to learn from countries that have improved their attendance rates.

However, he adds that “this needs to be done with a clear emphasis on context - as we know that effective strategies to support improved attendance are rooted in knowledge of individual schools, communities and pupils”.

Since taking office, Labour has made attendance a key focus. Will the government take heed and use this international data to learn from those nations that have improved attendance?

Whether it does or doesn’t may well be evident in 2028, when the next Timss study is published.

The Department for Education has been contacted for comment.

For the latest education news and analysis delivered every weekday morning, sign up for the Tes Daily newsletter

Keep reading for just £1 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £1 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

topics in this article