Strep A: Why cases are rising and what schools can do

The tragic deaths of children in England, Wales and now Northern Ireland from invasive group A strep (iGAS) have resulted in the risks posed by infectious diseases rocketing back up the agenda for schools.

The latest data from the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) shows the scale of infections: so far this year, as of 14 November, there have been 2.3 cases of iGAS recorded per 100,000 children aged 1 to 4 compared with an average of 0.5 in the pre-pandemic seasons (2017 to 2019).

Among children aged 5 to 9, this falls to 1.1 cases per 100,000 children, but still far above the pre-pandemic average of 0.3 (2017 to 2019).

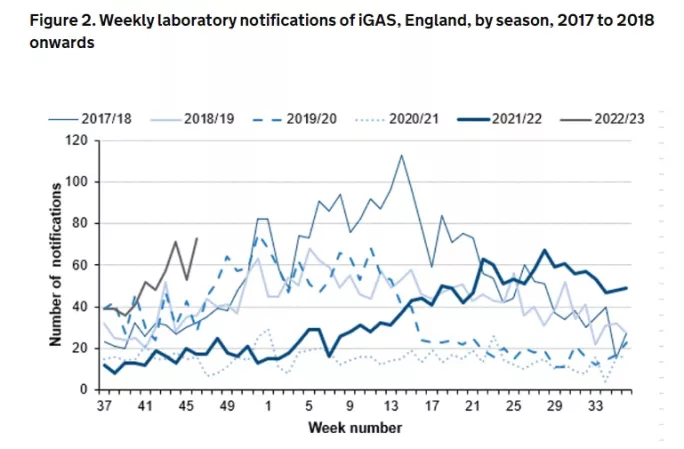

The graph below - in which the dark grey line represents this year starting from week 37 (12 September) - illustrates this increase starkly.

Source: Group A streptococcal infections: report on seasonal activity in England, 2022 to 2023

Sadly, 10 children are now believed to have died as a result of an infection this year.

This is more than double the number recorded in the last “high season” for group A strep infections in 2017-18, when the total was four.

These infections occur when a bacteria called group A streptococci gets into the bloodstream, where it can cause more dangerous conditions such as sepsis, meningitis and pneumonia.

Group A strep: the link with scarlet fever

More often than not, though, a group A streptococci infection leads to lesser illnesses and can be easily treated, as Dr Colin Brown, deputy director at the UKHSA, outlines.

“The bacteria usually causes a mild infection producing sore throats or scarlet fever that can be easily treated with antibiotics,” he says.

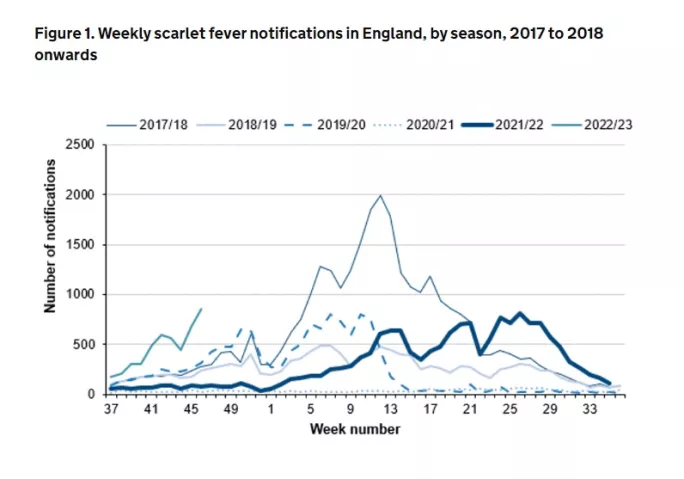

Scarlet fever cases are much higher than usual this year, something Shiranee Sriskandan, professor of infectious diseases at Imperial College London, says underlines why the risk from iGAS has increased, too.

“Outbreaks of scarlet fever (which is a very visible sign of Strep A infection) are a marker of how much Strep A is circulating in the community,” she explains.

Data from the UKHSA makes it clear how much higher than normal scarlet fever cases are, with it reporting a total of 4,622 notifications of scarlet fever received between September and mid-November - including a total of 851 notifications in week 46 (the week starting 14 November).

Source: Group A streptococcal infections: report on seasonal activity in England, 2022 to 2023

One unusual element of the current outbreaks that the graphs demonstrate is the time of year in which they are occurring, explains Dr Elizabeth Whittaker, honorary clinical senior lecturer at Imperial College London.

“High numbers at this time of year are unusual […] Usually we see a high number of cases in late spring or early summer, often after chicken pox infections,” she says.

So why is this happening?

Post-pandemic infections

A big cause appears to be the Covid-19 pandemic. For long periods of time children were kept apart through remote learning and social distancing, which meant they did not build up their immunities as they usually would.

As a result, this winter is either their first full winter virus season or their first in several years, and infections are occurring much more easily.

“During the first two years of the pandemic, we saw very little group A strep and it has started to circulate again in 2022 as restrictions have been lifted,” explains Dr Whittaker.

Professor Sriskandan concurs: “Children normally catch scarlet fever in their first year at school, if at all. We know that scarlet fever rates plummeted during 2020-21.

“We, therefore, think that school-aged children may not have built up immunity to strep A, and so we now have a much larger cohort of non-immune children where strep A can circulate and cause infection.”

Combine this with the usual winter flus and viruses and you have a situation where higher transmission and, therefore, cases are occurring - and sadly the risk of deaths is increasing as a result.

“Tragically, when there are high numbers of infections, the severe cases will also occur,” says Dr Whittaker.

What can schools do?

For schools, all of this is proving alarming and it adds yet more worry after the impact of the pandemic.

“It does seem to be new challenge after new challenge at the moment - and this is particularly worrying considering the tragic news over the last few days,” says one primary trust leader.

In response, this trust has returned to much of the risk assessment it employed during the pandemic, to help manage the situation, with regard to ensuring that any potential cases are spotted, dealt with appropriately and the authorities informed.

“We have also reinforced with staff the importance of hand washing, ‘catch it, kill it, bin it’ and other advice to support positive hygiene,” the trust leader adds.

Kulvarn Atwal, the executive headteacher of two large primary schools in the London Borough of Redbridge, says his schools are doing likewise to try and keep ahead of this “fast-moving situation” - with staff reminded of the importance of ventilation and encouraging regular hand-washing.

Rebecca Boomer-Clark, CEO of Academies Enterprise Trust, agrees that insights from its schools make it clear that it is a “rapidly changing situation” and one they are monitoring closely to help keep families informed - again calling on their experiences from the pandemic.

”As we did during Covid, schools will keep a calm head and make sure parents are fully informed of the latest guidance from the UK Health Security Agency,” she says.

Meanwhile, Robert McDonough, CEO of the East Midlands Education Trust (EMET), tells Tes that he is finding the situation “seriously worrying” and one in which there is a vague sense of powerlessness.

“All we have been able to do, as a trust, is to alert our school leaders to the guidance, ask them to look out for the symptoms in their children and to write to parents and advise the same,” he explains, adding: “In truth, I am not sure what more we could be doing.”

Wash your hands

The guidance he refers to was published in October entitled Guidelines for the public health management of scarlet fever outbreaks in schools, nurseries and other childcare settings and outlines the steps schools should take to spot, monitor and report cases.

Health experts tell Tes that the key element of the guidance is in section 5.5, entitled Outbreak Control, and specifically the good practical measures on hygiene - chiefly regular handwashing.

“Hand washing remains the most important step in preventing such infections,” it states.

“Good hand hygiene should be enforced for all pupils and staff, and a programme should be put into place that encourages children to wash their hands at the start of the school day, after using the toilet, after play, before and after eating, and at the end of the school day.”

Other key advice in the guidance for schools to follow states:

- Children and adults should be encouraged to cover their mouth and nose with a tissue when they cough and sneeze and to wash hands after sneezing and after using or disposing of tissues.

- Spitting should be discouraged.

- Breaching the skin barrier provides a portal of entry for the organism; therefore, children and staff should be reminded that all scrapes or wounds, especially bites, should be thoroughly cleaned and covered

Group infection control

The government, however, is considering going further than this guidance, with schools minister Nick Gibb announcing on Tuesday that the UKHSA was working with schools affected by outbreaks to provide help where required, including potentially giving preventative antibiotics to children in schools with confirmed invasive infections.

“This is an ongoing situation, the UKHSA are involved very closely with those schools and they will be providing further advice later on,” he said on GB News.

“But [providing antibiotics] may well be an option for those particular schools where there is an infection.”

Paul Hunter, professor in medicine at the University of East Anglia, says the fact that this is being talked about is significant because preventative penicillin is rarely administered unless absolutely necessary.

“If [infections are] scattered across the country and you’ve got occasional invasive infections here and there, and you never get second infections, then I think the pressure for widespread penicillin won’t be that great,” he tells Tes.

“But if you’re starting to see clustering of severe infections within schools, then I could well see those schools being given penicillin.”

He says making this decision won’t be easy, though, as giving penicillin to young children, especially those under the age of 5, can be dangerous.

“Children, if you give them penicillin, they get severe allergies and they can die. So if we treated this [situation] by giving penicillin to every child under 5 some of them would die from allergy to penicillin. Not many, but maybe more than from streptococcal infection,” Hunter explains.

“This is why the current national advice is that you should never do it [at a local level] unless you’ve discussed it at a national level.”

Reasons to remain calm

The rising number of deaths of previously healthy children will undoubtedly be alarming to everyone in education and the wider public, especially after the experience of the pandemic.

However, Dr Simon Clarke, a microbiologist at the University of Reading, says people should not be concerned that a new and more dangerous strain of group A streptococci has emerged.

“It’s important to remember that infections like this never occur at a constant rate. You get peaks and troughs in numbers and from that we work out an average,” he says.

“I’ve seen no data to indicate that a new strain is responsible for the current cases.”

Dr Chrissie Jones, associate professor of paediatric infectious diseases at the University of Southampton, adds that it is important to realise that the vast majority of infections will be easily treated.

“There are […] all the normal seasonal viruses going around at the moment, so many children will have a sore throat or fever but won’t have a bacterial infection caused by group A strep,” she explains.

“These infections will normally resolve without treatment, but if they are not getting better then it is important to seek medical review.”

Sharon White, CEO of the School and Public Health Nurses Association (SAPHNA), says its members are taking a measured view on the situation. “School nurses are taking a pragmatic view insofar as Strep A has always been around and impacted children,” she tells Tes.

For many, however, that will be cold comfort when you don’t know if your child or pupil may be one of those who do get progressively worse. Adam Finn, professor of paediatrics at the University of Bristol, told Times Radio it was understandable that parents and teachers were concerned.

“What we’ve got to do is get the balance right here. On the one hand not alarm people whose children are mildly ill - and there are a lot of mildly ill children around at the moment - and at the same time help people and support people to seek care and attention when their children become seriously ill,” he said.

To this end parents - and, by extension, teachers - are being told to look out for any of the warning signs that something may be happening that is worse than a usual infection.

“They stop eating, they stop responding, they sleep a lot, they might complain if they are awake of aches and pains and headaches,” said Professor Finn.

“They might have a rash or a sore throat or tummy ache, but they just get sicker and sicker. When you see that progressive decline, that’s the time to get the child to medical attention.”

Dr Jones lists the following as key symptoms to watch out for:

- A high fever that is not settling.

- Severe muscle aches, pain in one area of the body.

- A spreading redness on the skin.

- Breathlessness or having trouble breathing.

- Excessive sleepiness or irritability.

If you suspect any of these are occurring, the advice is to call a GP or 111 immediately and seek professional medical advice.

How does the outbreak end?

Of course, the other key question many will be wondering is: when will this outbreak end?

Hunter says that, sadly, there is no way of knowing. “The big question really is, are we going to see a relatively short peak that is over by the end of December? Or is this going to be a big peak that extends into the early part of next year? We don’t know.”

He says, though, that it will eventually “peter out”, noting that once the flu season is over it usually means other infections end, too.

“Once people who are susceptible get infected with flu it then dies out again, particularly as we move into the warmer spring months. So once flu dies out most of these other infections like strep, invasive streps...they fade out as well,” Hunter explains.

This reassurance will do little to quell the unease in leaders, teachers, school staff and, of course, parents about the situation, however, and all eyes will be on the UKHSA when it issues its next data on scarlet fever and iGAS infections.

Until then the best advice for schools is to maintain good hygiene and ensure that staff and parents know what to look for - and seek medical advice immediately if they have any worries.

Dan Worth is senior editor at Tes

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

topics in this article