Are NPAs really a qualifications reform trailblazer?

School awards night is in full flow and the bacon butties and stovies steaming away at the back of the hall are going down a storm. The catering team is fresh faced and a little shy at times, but they’re serving up the grub at an impressive rate.

And, all the while, they’re being assessed.

These are school students taking National Progression Awards (NPAs) in events and hospitality, at a level equivalent to Higher.

Unlike a Higher, though, their success will not pivot on a high-stakes external exam at the end of the much-criticised “two-term dash” - recalled with a shudder by generations of Scots.

Instead, they are graded continuously throughout the year. That could mean small summative class tests - or it could, as in this instance, mean being assessed against how they meet the requirements of serving up a successful buffet.

And even if for some reason they do not complete a full NPA, they can still walk away with some units; these are not all-or-nothing qualifications.

Plus NPAs are not an island. They are just one qualification among several - including Foundation Apprenticeships and Skills for Work - increasingly being embraced by schools keen to get away from the linear approach to qualifications that continues to command so much attention.

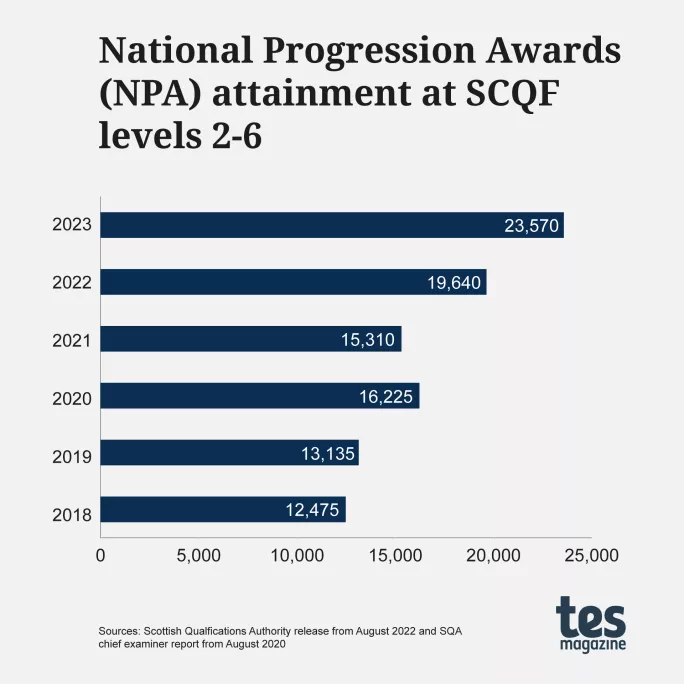

The growth of NPAs, however, is striking - as is the enthusiasm with which many teachers and school leaders talk them up. Between 2022 and 2023, NPA attainment - those passing the qualification - has risen by 20 per cent, and it has almost doubled since 2018.

The raw numbers are fuelled by teachers who extol the potential of NPAs to transform the experience of the senior phase for many students - or just to keep them in the senior phase at all.

Many teachers talk about the motivational boost of NPAs to students who had otherwise been hard to engage, of how they help keep more students in school until the end of S6 - a growing priority for teachers who have seen evidence that staying at school longer correlates with success after school.

The absence of exam-based assessment and the “real-world” application of NPAs - in courses as varied as criminology, esports, Gaelic songwriting and end-of-life care - hold big appeal to many students.

There are caveats, however. While growing fast, the number of students taking NPAs remains relatively small against more “traditional” qualifications. Not all schools are wildly enthusiastic about them, either, and some suggest the lack of an exam means NPAs are too easy a way to inflate attainment statistics.

Sceptics also point out that university entry requirements still lean heavily towards the more established Higher and Advanced Higher qualifications.

The advantages of NPAs

Nevertheless, NPAs are an increasingly common feature of the attainment picture in Scotland, and it is not hard to find schools willing to talk up their potential.

In computing, there are “lots and lots” of NPAs and, so far, Tracy Mutter - a computing and digital learning teacher at Falkirk High - has delivered six: computer games development, web design, software development, cybersecurity, digital media and digital media animation.

Mutter says expanding the offer in her department has meant retaining students who would not have coped with National 5 - or who had achieved an N5 but would struggle to make the leap to Higher.

One big advantage of NPAs, she says, is that they are continuously assessed and have no “big exam” at the end.

She adds: “There are some children who are really strong in class but when it comes to the prelims or the exams, they are nowhere. Because of anxiety, they just don’t do well in a stressful exam situation - but they are perfectly fine with the NPA.”

A practical aspect

Mutter says NPAs are broken down into units and assessments provided by the SQA, although it is possible for teachers to develop their own. Some outcomes, for example, depend on online multiple-choice tests.

“On face value that seems quite easy, but they are not one correct answer and three obvious red herrings - they actually do have to think about the questions and the suitable answers,” she says.

Students must also undertake practical tasks. In the computer game development NPA, the first unit requires them to develop a game proposal, plan the characters and the landscape, and then design the user interface. By the end of the course, students will have created a working game.

“Although they have assessment tasks, it’s more a portfolio of evidence they are generating as they go,” explains Mutter.

It is a frustration for schools, Mutter says, that there is a disconnect between the growing variety of courses on offer and university entrance requirements: more computing departments are embracing NPAs but the recognition they get depends on the university and the course, says Mutter, so there is a sense that higher education is “adrift” from what is happening in schools.

However, she stresses that there is more than one route to university. Two S6 students last year, for example, were planning to go to college for two years and then articulate across into the final two years of a degree at the University of Stirling.

‘Although they have assessment tasks, it’s more a portfolio of evidence they are generating as they go’

Mutter is not alone in her enthusiasm. The senior phase, for so long rigidly defined by three years in a row of high-stakes exams, is becoming a far more diverse landscape. Some schools have introduced dozens of new qualifications “pathways” for senior students in recent years.

That trend has been bolstered by the Hayward review, published in June, which proposed that external exams be scrapped for all qualifications below Higher.

A “Scottish Diploma of Achievement” would be introduced, detailing students’ interests and achievements far beyond traditional academic attainment, including volunteering, part-time jobs and Foundation Apprenticeships.

It will also encompass interdisciplinary projects, which the Hayward report said could allow an in-depth exploration of “a global challenge such as climate change, social justice or migration”.

Supporters say new qualifications - including NPAs, but also Skills for Work and Foundation Apprenticeships - are more adaptable and dynamic because they are not in thrall to the annual exam cycle.

This means they can pivot more easily to embrace growing areas of interest - such as climate change - and the needs of employers.

‘A dynamic and changing offer’

Not everyone is convinced. Some headteachers fear that NPAs and other new qualifications have little currency outside schools and that National 5s, Highers and Advanced Highers should remain the main focus. A significant minority of secondaries in Scotland continue to lean towards a more traditional curriculum.

So, what do schools that have embraced qualifications such as NPAs say to the detractors?

When Lynne Hollywood joined Johnstone High in Renfrewshire in 2015, the school had “a very traditional offer” that was “all geared up to the young people going to university”.

But that was “only ever going to be around 40 per cent of the cohort” - the other 60 per cent were not being given “a sufficient reason for coming back” in S5-6, she says.

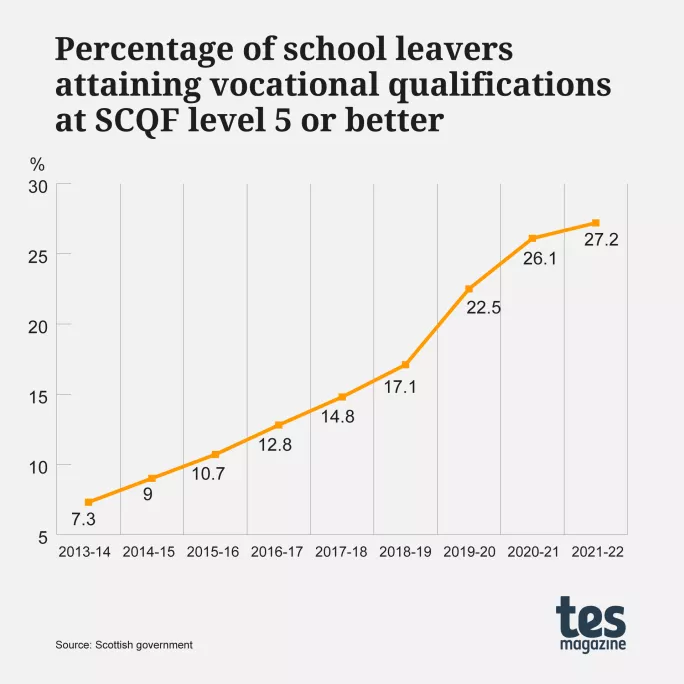

Now, the school has “flipped it”. Every year, there is “a dynamic and changing offer” based on students’ interests and the local economy - and 40 per cent of senior students are studying for vocational qualifications.

At NPA level, the school offers (from 267 NPAs recorded by the SQA in its most recent data) science and technology, animation, jewellery, customer service, criminology and cybersecurity. There are also qualifications in cake craft, Scottish studies, personal finance and sports refereeing.

The upshot, says Hollywood, who is now head, is 99 per cent of students now go into “positive destinations” - university, college or employment - when they leave school, up from 86 per cent when she arrived at Johnstone High.

Is university the be-all and end-all?

The proportion going to university has dropped - from 44 per cent in 2018-19 to 36 per cent based on the latest figures - but Hollywood is sanguine.

“A lot of people think the be-all and end-all is getting kids into university. Absolutely not. The be-all and end-all is getting children into the correct place, the correct pathway, and listening to their views to shape a senior phase offer that suits them,” she adds.

For Colin Meikle, headteacher of Craigmount High in Edinburgh, the attraction of offering qualifications such as NPAs was in broadening course choices, given that only half of leavers go on to university.

Another big attraction for Meikle - who says the number of vocational courses at his school has trebled in two years - was the opportunity to allow students who disliked high-stakes exams to be assessed differently.

“A final exam or even a mix of coursework and an exam does not suit every learner,” he says. “Some people cope better with regular assessment over the course of the year and therefore courses like NPAs, National Certificates, Higher National Certificates and Skills for Work just allow young people to have their attainment recognised in a different way.”

A spark that led this new approach to the senior phase was the 2014 Developing the Young Workforce report.

Ollie Bray - an Education Scotland strategic director who, as a headteacher, was among the first to embrace the wider qualifications offer - says it gave schools permission to expand their vocational offer and to run qualifications that had previously been seen as the preserve of the college sector, such as NPAs.

The DYW commission, chaired by oil and gas tycoon Sir Ian Wood, found Scottish schools were “largely focused on [students] with academic aspirations” and that there was often “no pathway nor destination” for others, who were “fast becoming bored and frustrated”.

Hollywood, however, now talks about students at her school being able to effectively “live” in certain departments because National 5s and Highers are not the only qualifications available - they can amass a whole range of qualifications in their areas of interest instead.

A smaller gap to bridge

Another benefit, heads say, is that students do not get stuck between two levels: the leap from National to Higher, for example, is widely seen as too big for many, and qualifications such as NPAs can provide an alternative or even a bridge to Highers.

There are still barriers to schools embracing this wider offer, not least the sheer overwhelming variety of qualifications now on offer.

In 2018, Tes Scotland visited Bray at Kingussie High to write about the wider range of qualifications at the school, including an NPA in beekeeping. At that point, Bray questioned whether teachers and heads fully understood the range of qualifications available in Scotland.

Now, Bray says things have “definitely improved”, with “more and more schools taking the risk” and comparing notes about the impact of NPAs and other qualifications.

Cluttered qualifications landscape

However, when the Withers review of skills was published in June, it sounded alarm bells about a cluttered qualifications landscape.

Author James Withers, in a Twitter thread to coincide with the report, said he ended up with a headache after seeing the “bewildering array of acronyms and terms” in his son’s senior secondary course options.

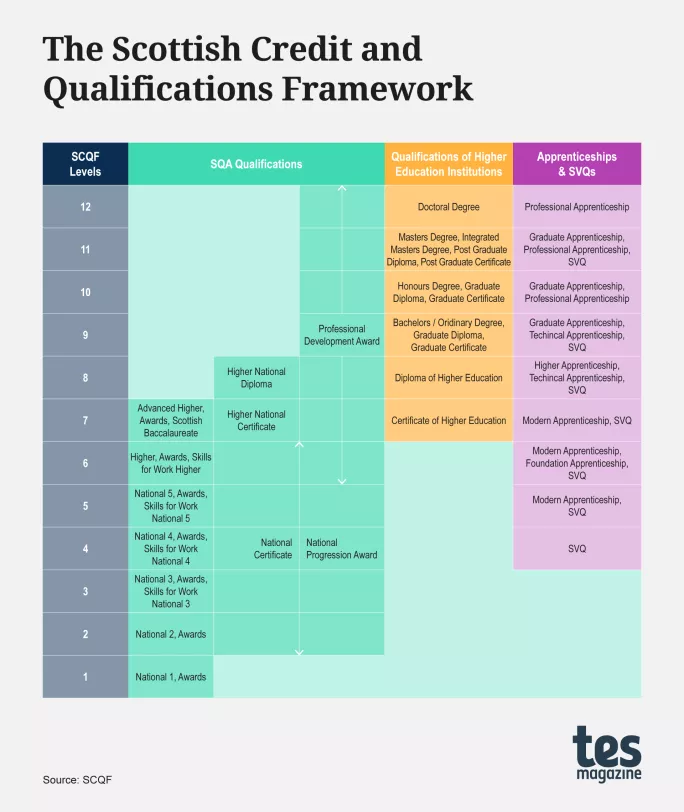

Withers suggests the answer was to make better use of the Scottish Credit and Qualifications Framework (SCQF), which “comprehensively maps qualifications against the various learning levels, enabling clear comparisons of each pathway”. In other words - as Withers put it - if a Foundation Apprenticeship or an NPA is equivalent to a Higher, why not give them all the same name?

Bray was ahead of that curve in his time as a head: he spoke about SCQF levels - as opposed to Highers, NPAs or any other qualification - when trying to explain the equivalence between course options to parents and students.

But the Scottish government has so far shown little appetite for getting rid of the distinct Higher brand, which has been around for some 130 years.

This makes Donnie Wood’s job a difficult one.

Wood, a development officer for the SCQF, travels around Scotland trying to convince schools to embrace the full range of qualifications. Some 220 secondaries (mostly state schools) are involved in the SCQF School Ambassador Programme, which aims to help schools broaden their curriculum.

But the idea that “the Higher is the gold standard” is deeply ingrained, he finds - and change becomes even more difficult when schools are being benchmarked on more traditional qualifications, rather than the SCQF levels where Highers and NPAs are on a level footing.

Defining success

Giving evidence to the Scottish Parliament’s Education, Children and Young People Committee this month, headteacher Peter Bain said that some “brave” headteachers and councils were resisting pressure to, for instance, maintain the proportion of students passing five or more Highers, or five or more National 5s.

Instead, they were “prepared to tell the full story about the success of individual schools”. But that pressure about how success is defined was still there, he said.

In February, research funded by the Nuffield Foundation and carried out by University of Stirling researchers found that Scottish schools’ performance was judged on a narrow range of data that favoured more traditional qualification.

This was leading to “counter-educational” practices in schools, including “abolishing low-performing subjects”, “teaching to the test” and “channelling students into courses to benefit school attainment statistics”.

Meanwhile, headteachers regularly gnash their teeth at unofficial league tables that fixate on Highers and ignore a whole gamut of other qualifications.

Some argue for more of a focus on tariff points as an antidote: all Scottish qualifications garner points and if this were the key means of judging performance, it is argued schools would get credit for all the different types of courses they run.

‘A lot of people think the be-all and end-all is getting kids into university. Absolutely not’

There are lessons that can be learned from England when it comes to a points-based system, says Alistair McConville, deputy head at the independent King Alfred School in London and co-founder of the Rethinking Assessment group of school leaders.

McConville says England had a points-based system but then school leaders started to game the system by putting students forward for qualifications that were easier to pass - but not necessarily best for them - to boost their school’s headline scores.

That resulted in the government putting the focus squarely back on to traditional GCSEs and now, he says, schools do not diversify the qualifications they offer because it would affect their league table position or result in a negative Ofsted inspection.

However, McConville believes a system based on tariff points can work as long as accountability measures are proportionate so that “schools are freer to make child-centred decisions about what courses they are going to do”.

McConville is generally enthusiastic about what he sees in Scotland - giving students more choice over the range of educational experiences they get is “a good thing”.

“Scotland is like the promised land as far as I’m concerned,” he says.

False division

Even so, there remains much to do. Withers’ report, for example, identified a “hugely damaging” and “completely false division” between “vocational” and “academic” pathways - genuine parity of esteem “remains an illusion” in too many cases.

And while Scottish school accountability measures might seem a lighter touch than in England, they can still heavily influence the decisions taken by schools.

Yet, many schools are undeterred and continue to diversify their timetables, because they can see the value of a wider range of qualifications for their students. NPAs are just one part of what headteachers such as Hollywood see as “a sea change” in Scottish schools that needs to be more widely publicised.

“The Higher is a brilliant qualification; it opens doors for young people,” she says. “But that is just a small part of the SQA catalogue and everything that’s out there for our young people.”

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

topics in this article