Is time running out for the EBacc?

There isn’t much in schools that escapes being subjected to targets: everything from attainment to attendance seems to have a key performance indicator.

Some are achieved with ease, some are a struggle for a while before solutions are found and some are quietly forgotten about.

There is one target, however, that remains a perennial problem without an obvious solution: the English Baccalaureate, or EBacc for short.

When it was introduced in 2011, the idea was that it would promote a set block of subjects that the government believed would help keep a pupils’ options open for their future studies.

To this end, the EBacc comprises of:

- English language and literature

- maths

- the sciences

- geography or history

- a language.

The government set lofty targets for the Ebacc, with an expectation that 75 per cent of students would be studying the subject combination at GCSE by 2022 and 90 per cent by 2025. It was always ambitious but it now appears downright unrealistic.

After all, last year Tes wrote about the difficulty schools faced when trying to encourage EBacc take up, with just 38.7 per cent of students entered for the combination of subjects in 2021.

Meanwhile, data from this summer’s exam results suggests things have got worse, not better.

The MFL issue

Although the official figures are yet to be announced, we know where the problem lies - modern foreign languages (MFL). For example, in 2021, of the 61.3 per cent of pupils not doing the EBacc, 87.3 per cent of them were missing the MFL component.

We know the problem has persisted this year, too, as 7,156 fewer students took French, German and Spanish GCSEs, suggesting the number of pupils studying an EBacc combination of subjects could drop once again.

As such, getting anywhere near 75 per cent is unrealistic. This reality led Professor Alan Smithers to write in a report for the University of Buckingham’s Centre for Education and Employment Research that the EBacc is “done for”.

So, is it time to say “au revoir” to the EBacc?

Nick Gibb, former education minister and champion of the EBacc, says not, telling Tes that the subjects it covers are ones that all students “have a right to study”.

“Children from an advantaged background have parents who will assume their children will be studying those subjects to 16,” he says. “All children from all backgrounds deserve that right.”

In fact, Gibb says the argument to scrap the EBacc amounts to “the soft bigotry of low expectations” and says it is essential to retain that combination of subjects to allow students from every background access to a good education.

“It’s very important for social mobility and social justice to study the subjects most advantaged pupils take for granted,” he adds.

However, Robert Halfon, chair of the Education Select Committee, believes the data proves that the EBacc needs reforming at the very least.

“The EBacc needs to be reformed to create a parity of esteem for vocational and skills-based subjects alongside a rigorous academic offer,” he says.

Furthermore, he argues that since the EBacc has been introduced, it has led to a narrowing of the curriculum that has “squeezed out” other subjects - something that has actually reduced pupil choices rather than increasing them.

“Subjects like design and technology (DT) and computer science are being squeezed out, with entrances for DT GCSEs down by 65 per cent from 2010,” says Halfon

It’s a concern shared by Tom Richmond, founder and director of EDSK, an education and skills think-tank. He says the target has led to an “entirely unjustified bias” in favour of the EBacc subjects and questions why the subject combination was chosen in the first place.

“The Department for Education’s main justification for the EBacc was that it would assist with entry to the most selective universities because the EBacc subjects closely matched the list of ‘facilitating subjects’ published by the Russell Group of universities,” says Richmond.

“The Russell Group withdrew its facilitating subject list several years ago because it had led to ‘misinterpretation’, yet the EBacc has continued as if nothing happened.”

Although Halfon and Richmond say the time is up for the EBacc, they have different ideas about what should replace it.

Halfon is in favour of replacing the measure altogether and thinks we should look to our European neighbours for a solution.

He praises the broadness of the International Baccalaureate, particularly the “creativity, activity and service” involved for students, and says he would like to see a “British Baccalaureate” introduced along similar lines.

A British Baccalaureate “would end the false dichotomy between vocational and academic achievement that has unfairly constrained our young people for decades”, he says.

“To adequately prepare pupils for the future world of work, we must ensure they are equipped with the skills needed to meet the jobs heralded by the Fourth Industrial Revolution.”

The role of Progress 8

Gibb isn’t convinced. He says that the “knowledge versus skills” argument is flawed, and that you can only teach “critical thinking and problem solving if you have studied a knowledge-rich curriculum”.

Richmond, meanwhile, would prefer the EBacc measure to “be withdrawn with immediate effect” and, instead of introducing a new measure, using an adjusted version of Progress 8.

In its current form, Progress 8 requires English and maths plus six other subjects, three of which must be EBacc subjects. Richmond would like this updated to allow a free choice of any six subjects.

This would mean all pupils can study the subjects “that suit their interests and abilities”, he says.

Sir Peter Lampl, founder and chair of the Sutton Trust and chair of the Education Endowment Foundation, also believes that reform is needed to make sure the focus on EBacc subjects does not detract from other areas of the curriculum.

“As we look to the future of the EBacc, all students should have the opportunity to study the full range of academic subjects, particularly the most disadvantaged,” he says. “It is vital that studying the EBacc does not come at the expense of arts and vocational subjects.”

Gibb, though, argues that this misses the point of the EBacc set-up, which was “designed to be small” and allow plenty of scope for pupils to study a broad range of subjects around it.

“Studying EBacc takes up just seven subjects, so that still leaves 1 or 2 options…to study an art, or a technology,” says Gibb.

This may be true but, as the above data makes clear, the reality is that many students are not taking the EBacc combination of subjects, let alone worrying about fitting in other subjects around it.

How to fix the MFL issue

If MFL is the problem to achieving the EBacc targets, would Gibb consider that component being dropped?

Gibb says no, arguing that as a “trading nation”, children in England should be taught MFL, and points to the rise in entry for community foreign languages at GCSE as an indication that there is an appetite for language learning in schools.

Alex Crossman, headteacher of the London School of Excellence, a 16-18 free school, agrees that MFL should remain: “Employers continue to value fluency in a second language and independent school students almost all learn a second language to at least GCSE level,” he says.

So, if MFL is to stay, what needs to be done to get more pupils (and their schools) to choose it?

David Blow, chief executive of South East Surrey Schools Education Trust, says one issue that must be dealt with is grading.

“Unless they address the grading to truly bring it in line, there will be a permanent challenge and disadvantage, as MFL needs to be in line with other EBacc subjects,” he says.

There are two problems, here: first, Spanish appears to be graded more generously than French and German, with more students passing and receiving the top grades.

The second problem is the belief that MFL as a whole is marked more harshly than other subjects. In 2018, German grades were a whole grade lower than a pupil’s average grade in English and maths. French was 0.86 grades lower and Spanish was 0.67 grades lower.

Ofqual has been happy to help on the first problem but not the second; it produced a report on the inter-subject compatibility between French, German and Spanish in 2019. This led to grades in French and German being “boosted” in 2022.

Speaking to Tes before the 2022 exams, Ofqual’s chief regulator, Jo Saxton, explained that the watchdog “did a lot of work looking at comparisons” and that, as a result, “would make an adjustment to the way French and German are graded, to bring them in line with the grading in Spanish”.

This adjustment resulted in grades rising in MFL when they dropped everywhere else. Students scoring 4 and above in French and German rose by 8.4 and 7.7 percentage points respectively.

However, Blow says the “boost” didn’t go far enough and that top grades in MFL are still too hard to obtain.

“From a school point of view, you get higher grades if children choose history and geography, and this makes MFL is less attractive,” he says. “Grading needs to be addressed to encourage more take-up.”

Language reforms

Statistician and education analyst Dave Thomson, from FFT Datalab, agrees that although changes this year were “welcome”, more needs to be done, as pupils are still more likely to achieve grade 3 or lower in MFL than in English and maths.

“Bringing [French and German] in line with Spanish will still leave MFL more severely graded than other subjects,” he says.

Gibb believes the changes made by Ofqual for GCSE do go far enough to fix these issues, but he admits that grading for A-level MFL needs to be addressed. This could help with MFL take-up at GCSE by making the subjects more compelling to study at the later stage, he says.

The promise of “fairer grading” is only one part of the picture, though, says Crossman, who argues that the entire way GCSE MFL subjects are taught needs rethinking.

“Too few students have a positive experience of learning a second language in secondary schools,” says Crossman. “This is what puts students off studying the subject.”

Change is on the way, though, with the new MFL GCSE reforms taking effect from 2024 and first examined in 2026.

The review that led to these reforms was undertaken while Gibb was education minister, and a report was produced that looked at the best way to teach it.

He recalls how he would “receive letters from young people who didn’t enjoy it” that led him to “think there is room to improve how languages are taught in schools”.

The changes were unveiled in January this year and, most notably, contained plans for set vocabulary lists that the chair of the commissions that oversaw these reforms, Ian Bauckham, said would help boost language learning.

“Making sure that students really know the basics is essential for those taking their languages to further study,” he wrote in Tes.

Others disagreed, with Geoff Barton of the ASCL, for example, claiming that it would “alienate pupils and prove counterproductive”.

Blow is also not expecting great things from the curriculum reform in 2024 - in his experience, the changes that have been made to MFL to prepare for the reforms have not helped take-up and, consequently, EBacc entry.

He cites the British Council Language Trends report, which shows that more than a third of secondary schools report students as early as Years 8 and 9 dropping a language.

The writer of the report, Dr Ian Collen, who is director of the Northern Ireland Centre for Information on Language Teaching and Research, drew the alarming conclusion that teachers believe the reforms - intended to reverse the decline - were instead going to accelerate it.

“Teachers in general do not appear convinced that the new GCSEs in French, German and Spanish in England are going to lead to increased pupil motivation, sense of progress and, thus, uptake.”

Lisa-Marie Müller is head of research at the Chartered College of Teaching. She makes the point that the new curriculum has been criticised for its “lack of focus on literature, culture and communication”.

This, in turn, makes motivation to study MFL even harder for teachers to instil in pupils. “If we want more students to take on a language at GCSE, and thus to increase the number of EBacc students, we have to try and increase motivation,” she says.

“It remains to be seen to what extent the new curriculum will be successful in achieving that goal.”

On top of all this, many schools face trouble recruiting enough MFL teachers - another barrier to helping them potentially meet their EBacc targets.

For example, in a recent Tes report, Vic Goddard, co-principal at Passmores Academy, described the school recruitment situation for MFL as “hopeless”. Meanwhile, Brexit has made it harder to hire in teachers from Europe with the necessary skills.

Gibb, though, is optimistic about future recruitment potential, noting that the move to put MFL teachers on the migration advisory list could help, as could changes to rules around the recruitment of international teachers.

Limiting options

However, even if MFL issues were resolved, it would not be the silver bullet for the EBacc - other issues exist, too.

For example, because it requires a humanities subject, there has been a move to teach them at the expense of time for other subjects, with FFT Datalab noting that there has been a drop in take-up of non-EBacc subjects at GCSE since the target was introduced: “Geography, history and computing - a new subject introduced in 2014 - have been the main beneficiaries of the EBacc,” the authors noted

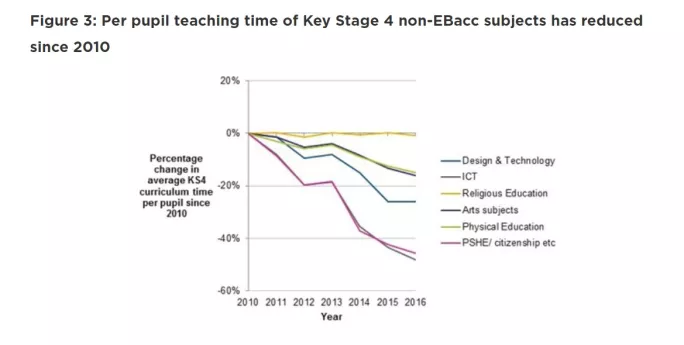

Furthermore, a report from the NFER in 2017 found that since the introduction of the EBacc, students’ timetables in Years 7, 8 and 9 now have less time given to subjects such as the arts, PE and PSHE.

“The demise of key stage 3 assessments after 2013 has given schools more flexibility in when pupils move from the KS3 curriculum on to GCSE study,” wrote report authors Joana Andrade and Jack Worth.

“This may concern some in the school system if it is leading to the range of subjects pupils are studying narrowing earlier than it has done.”

The impact on KS4 has been clear, too, confirming that concerns about the EBacc reducing focus on non-EBacc subjects have come to pass in many settings.

Source: NFER

Should Ofsted have a role to play?

That’s not say that there have not been successes since the EBacc was introduced.

Gibb makes the point that since the EBacc, uptake of GCSE double science in England has risen from 63 per cent in 2010 to 96 per cent in 2019.

“What is wonderful about that figure is that once you reach 96 per cent, then you’re talking about almost everyone,” he says.

“And that means that everyone, including disadvantaged children, is studying double science. It’s one of the statistics I’m most proud of as a consequence of the EBacc.”

Meanwhile, Sir Peter cites research in 2016 that looked at the impact the introduction of the EBacc had upon student outcomes and found that, despite leaders’ reservations, students “largely benefited from the curriculum changes and were more likely to achieve good GCSEs in English and maths”.

This is good news, particularly for previously lower-attaining pupils, who the report says saw “significant improvements in their maths and English grades”. And, when looking at pupil premium students in this group, there is evidence that they are “the greatest beneficiaries”.

Given that there are ongoing efforts to try to close the disadvantage gap in education, this is not insignificant.

Overall, it’s clear that slicing up data from EBacc uptake, the subjects in play can present various narratives depending on your point of view.

But there’s no escaping the reality that the top-level 75 per cent target remains a way off.

Tes asked the DfE if it was still intending for the target to be hit or if there were plans to amend it. The department’s reply suggests it is looking at its glass and is determined to see it as half full.

”We have successfully exceeded our 75 per cent uptake ambition across four of the five subject groups offered by EBacc,” says a DfE spokesperson.

Tes also understands that, at present, there are no plans to move or adjust the EBacc targets.

All of the DfE hopes appear to be pinned on those controversial MFL curriculum changes.

“We have reformed the modern foreign language GCSE curriculums to encourage more students to take up these important subjects and have increased bursaries for languages to attract more talented teachers to the profession,” says a DfE spokesperson.

For Gibb, though, there is another option on the table - bring Ofsted into the equation: “You shouldn’t be graded ‘good’ on quality of education if your EBacc is below national average,” he says.

It’s a bold ask but one that Blow agrees with, arguing that Ofsted needs to issue a “direct instruction” on the teaching of languages as “part of a broad and balanced curriculum” and that the threat of the stick would motivate schools to address the problem.

In an era of high-stakes accountability, that’s an idea that may repulse some but, given that the target remains so far off, it may be the only resort the government has if it truly wants to meet its targets.

Gibb has one final, more palatable, idea - push the deadline back: “I thought we should set a later date for the target, especially because of the challenges of Covid, but I think we should still be striving to get 75 per cent,” he says.

“We just have to try harder.”

Grainne Hallahan is senior analyst at Tes

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

topics in this article