Why vocational music courses are proving so popular

This article was originally published on 26 May 2023

“Britain’s pop music is an incredibly successful and iconic part of the country.”

Norton York, chair and founder of RSL Awards, which provides vocational qualifications (VQs) for music from levels 1 to 4, is reflecting on why he thinks courses focused on modern music techniques have exploded in interest over the past decade.

A glance at data for VQs from the main providers - RSL, BTEC, NCFE and UAL - at levels 1 to 3 for a raft of music courses offered shows how rapid this growth has been.

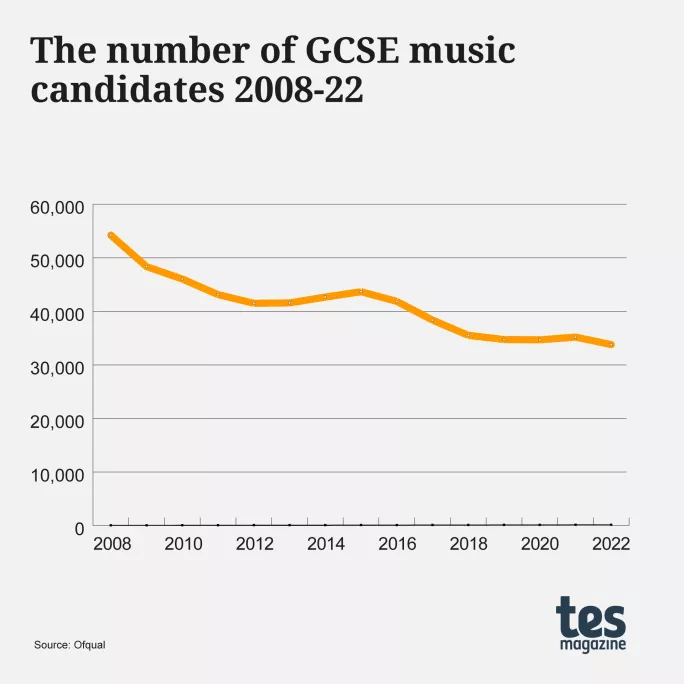

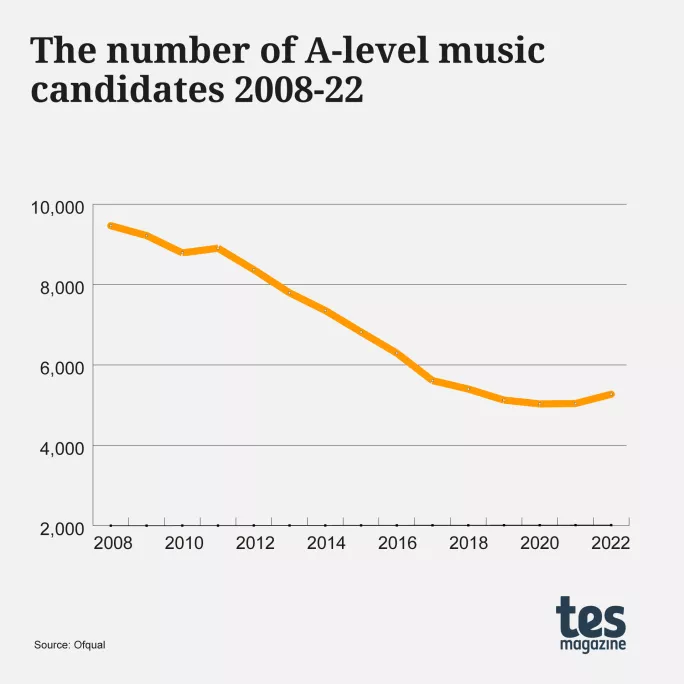

What’s more, when you compare this with the decline and stagnation of GCSEs and A levels, the situation is even starker.

For most in music and education, it has been the two lines trending downward that have been of most concern and focus.

For example, a 2019 report by the Musicians’ Union warned that music was being “squeezed out” of both primary and secondary schools, while a 2020 report found the pandemic has put a stop to many music lessons.

What’s more, in March this year, a 118-page report by the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, entitled The Arts in Schools: Foundations for the Future, warned music was being relegated in favour of other subjects, driven in a large part by the English Baccalaureate.

“The prioritisation of EBacc (non-arts) subjects in secondary accountability measures has meant a reduction in the level of arts subjects, teachers and resources available, and therefore declining GCSE and A-level take-up,” the report notes.

However, for York, that report and wider worries around the decline of GCSE and A-level music ignore the rising interest in VQs in schools that serve as a counterpoint: “It’s frustrating that negative figures are always used to suggest there is a major problem,” he tells Tes.

“There are legitimate issues of funding [for music education], of course, but we can see there is no lack of interest in music study in general.”

Indeed, as the above chart shows, VQs have been a major success story driven by the four main providers in this area. For example, in 2021, when 32,330 VQs were taken, these were split up as: BTECs by Pearson (17,170); RSL (8,530); UAL (4,725); and NCFE (1,905).

A ‘quiet revolution’ in music education

These figures represent a huge increase since 1994 when the first VQs were offered, with just 83 taken.

York says the growth over this time has been something of a “quiet revolution” in education as providers recognised that providing practical, pop music-orientated courses based on instrumentation, songwriting, production, performance and more would meet a demand not previously met.

“The music education establishments behaved as if it was slightly inconvenient that there was this pop music development in the world,” he adds.

The revolution he mentions led not just to new VQs from firms like his own or Pearson, but also new courses at the University of Westminster and the University of Salford, and entirely new establishments such as the Liverpool Institute for Performing Arts, the BRIT School and BIMM Institute in Brighton.

These courses and establishments have gone on to launch the careers of numerous stars such as Adele, Ed Sheeran and Kate Nash, and producers such as Fraser T Smith.

All this has made schools - both state and international - sit up and take notice of VQs, hence the rising numbers seen above.

VQs have also gained awareness in the corridors of power, with Baroness Barran countering a question in the House of Lords last year about GCSE and A-level decline with positive vocational data.

She said: “While…uptake of the GCSE has declined, uptake of the VTQ - the vocational qualification - has increased, so actually there are almost 53,000 children today taking either the GCSE or the VTQ, compared with almost 50,000 in 2016.”

‘We need a rich portfolio of qualifications in creative subjects to cater for the diverse practices in the industry’

Furthermore, in June 2022, the government issued its national plan for music, which stated that, while it “would like to see an increase in students studying for GCSE and A-level music”, it was also “committed to retaining key high-quality vocational qualifications at key stage 4” and “all secondary schools should be offering qualifications at this level”.

One school doing this is The Bewdley School in Worcestershire, where both routes are offered at KS4, as head of music Helen Blythe explains.

“We could see we had students who wanted to do the more traditional GCSE route, but a significant number who were much more vocationally based - musicians, singer-songwriters, music technologists who want a more practical option,” she says.

This led them to offer courses from RSL and GCSE and, since then, they have seen uptake surge: “We run two options groups each year and we have about 25 students in each group.”

Meanwhile, for its sixth-form students, because only “one or two students” ever did music A level, the school now offers only VQs at this stage, opting first for the BTECs from Pearson before switching to RSL.

Since making the switch to VQs, Blythe says interest has soared, with many more students taking music and “one or two students each year” usually going on to study music “at BIMM or university”.

It’s a similar tale at an international school in the Middle East, where a head of music explains that they introduced VQs having used them previously at a private school in England where they witnessed the clear interest from students.

“My reason for introducing a new course was due to past students informing me they felt practically underprepared for the fast-changing real-time world of music and drama,” they say.

“Analysing symphonies is outdated and not current in the industry. Practical musicianship is what universities, colleges and workplaces are looking for.”

And, like The Bewdley School, the school is also dropping traditional A-level music from September 2023.

Steven Berryman, director of creativity, music and culture at Charter Schools Educational Trust (CSET) and a music teacher by training, says his trust is also exploring the possibility of offering VQs from UAL, alongside GCSEs and A levels, to fill a gap that those options do not cater for.

“I think we need a rich portfolio of qualifications in creative subjects to cater for the diverse practices in the industry,” he notes.

York says he hopes such examples will show schools other options are out there and can help engage more students in music.

“[VQs] are a way for teachers to think: ‘How do I get my music department to reach out in a meaningful way and offer something to students who wouldn’t normally [study music]?’”

Underlining the importance of using VQs to reach these new students, he cites research from 2019 into A-level music candidates and their Participation of Local Areas (POLAR) data, which groups young people into five quintiles based on how likely they are to participate in higher education. The research found that “at least 60 per cent of A-level music entries each came from schools in postcodes with POLAR ratings of 4 or 5 [the highest levels]”.

Conversely, data from RSL’s 2020-21 cohort of around 8,000 students found 70 per cent of its students were within levels 1-3 in POLAR. Furthermore, it also found that 65 per cent of students on its courses are in the lower 50 per cent of multiple deprivation.

“This means we are appealing to a different cohort, who otherwise wouldn’t have been doing music at level 3,” adds York.

A spokesperson for Pearson says they, too, have seen a clear rise in interest in its BTECs in this area driven by new learners engaging in music courses.

“This [increase in VQs] may be because the rise of accessible music creation software and new music-making technology, for example, has attracted young people who create and perform music in new ways,” they said.

“These learners may be more suited to, or interested in, the vocational, industry-focused product-making approach that the BTEC music courses offer.”

Oliver Alcorn, head of music technology at The Bewdley School, agrees that without VQs, many students would never have pursued music: “I think that they just would have been switched off by the GCSE.”

However, despite this growth and rising interest, York says too many students are still “switched off” from music study because GCSE is the only option they have.

“As an average in most schools, around 93 per cent of kids, when they get to choose whether they carry on with music and the option is GCSE music, don’t do it,” he says.

The future of music qualifications

Given, then, that VQs seem to be capturing the interest of more young people, should GCSEs and A levels become more vocational by design, too, to appeal to more students?

York says it is something the government needs to think about, while Berryman says he thinks there is scope for changes to be made: “There is room for [music] GCSEs and A levels to further embrace the diversity of musical practices today - particularly technology,” he notes.

However, he adds that he would be wary of GCSEs or A levels changing too much as, if they became too similar to the VQs, it could be a backward step by reducing choice in the market: “I think there are merits in vocational industry-inspired qualifications, as well as what the GCSE and A level offer.”

Pearson’s spokesperson, perhaps unsurprisingly given that they offer courses at GCSE and A level, also said having the variety was better for learners.

They said: “As well as providing differing course content, some learners find they are more suited to the practical, hands-on approach to learning that a BTEC provides, with regular assessment throughout the course.

“Others welcome the classroom learning and combination of non-examined assessment and final exam-based approach that a GCSE or A level provides.”

The Department for Education, too, clearly has no plans to change this, with a spokesperson reiterating that, as part of its national plan for music education, it wants to see “music valued and celebrated in every education setting” - but that vocational qualifications are seen as a distinct component of this aim.

“We recognise the distinct and important role [VQs] play in supporting students to develop different skills from the GCSE,” a spokesperson said.

For the VQ providers, this is probably good news, leaving them to battle among themselves for the growing number of schools looking to add VQs to their offerings.

‘Analysing symphonies is outdated…Practical musicianship is what universities, colleges and workplaces are looking for’

However, for RSL, the situation is muddied by the fact that from September its level 2 courses will no longer count towards school Progress 8 data.

York says the situation is a “hassle” and he wishes the government would “stop changing the rules about whether or not we are on the [performance] tables” - especially as, at level 3, its courses do count towards performance targets and the university points system.

For now, he is sanguine about the situation, noting the majority of schools that use RSL at GCSE are “not worried” by this change and have stuck with them, and that the company will resubmit for level 2 accreditation in the coming years.

For The Bewdley School, though, the change has meant having to switch providers to ensure student outcomes can be measured, which is a major upheaval for staff who now have to learn and deliver an entirely new curriculum.

“The senior leadership team said everyone’s exam grade has to count [to performance tables] and I understand that,” says Blythe.

“We’re having to move to Eduqas’ performing arts. I think it’s really sad [that we can’t stay with RSL] and the minute RSL is approved, we’ll be back there.”

Given the growing popularity of such courses within schools, it seems at odds with the stated desire in the national plan for music for all schools to offer a vocational music qualification when one of the biggest providers has been removed from performance targets.

While not commenting directly on this situation, a DfE spokesperson said: “We introduced a rigorous new approvals process for these qualifications to ensure that all technical awards included on performance tables were high quality.”

For York and RSL, though, the hope is that the courses are reaccredited once again in the future for performance targets at level 2 and school demand for VQs continues to grow so a new generation of students is inspired to study music.

And who knows - perhaps the next icon in Britain’s pop music history will be unearthed as a result.

Dan Worth is senior editor at Tes

Register with Tes and you can read two free articles every month plus you'll have access to our range of award-winning newsletters.

topics in this article