- Home

- Teaching & Learning

- General

- Why US schools have fallen in love with scripted lessons

Why US schools have fallen in love with scripted lessons

While there’s no official way to measure it, scripted curricula seem to be on the rise in US schools.

More elementary schools are using structured, scripted lessons found in literacy curricula such as the University of Florida Literacy Institute Foundations owing to their positive research results in teaching pupils to read.

New teachers in Frederick County, Maryland, participate in “intellectual prep” before their lessons, going over scripts and specific moves - like how to hold a mini whiteboard - with principals and coaches to ensure lessons have pupils thinking and are at grade level.

In Houston, Texas, turnaround schools taken over by the state are breaking lessons down into seconds - for example: 10 seconds to log on to a laptop, one minute to read a passage, 30 seconds to pair-and-share with a partner.

The rise of scripted lessons

While teaching down to the second may seem extreme, researchers say a more prescriptive approach over what teachers say and do inside classrooms is on the rise throughout the industrialised West, not just in the US.

But in the latter, it appears a perfect storm of factors is pointing teachers toward a more exacting approach to teaching and learning that is seeing scripting become much more mainstream than elsewhere.

To be clear, scripting is not new in the US. As with much of American schooling, scripted lessons have swung back and forth on the pendulum of popularity over the past few decades.

But today’s version of this pendulum swing looks a little different than in the past. Similar to movements in the UK and Australia, recent laws and policies around the use of cognitive science and the “science of reading” to structure lessons are pushing more American classrooms toward scripted curricula based on scientific evidence of effectiveness.

More on education around the world:

- Why is France so good at keeping its teachers?

- How are schools tackling pupil absence around the world?

- How New Zealand has (almost) learned to love phonics

A new movement for high-quality instructional materials, or HQIM, in every classroom is a distinct departure from the idea of “local control” that often left curriculum decisions up to districts, schools and even individual teachers.

The ongoing teacher shortage is encouraging both schools and teacher trainers to get more new teachers on their feet sooner with the help of a heavily sequenced curriculum.

While some groups like the National Council of Teachers of English, a national advocacy group that boasts over 25,000 members, seem to have made it central to their mission to resist scripted reading curricula, national momentum is not currently on their side.

The evolving role of teachers

Many American educators and administrators see more scripted lessons as a return to a better way of educating pupils, especially pupils who come from disadvantaged backgrounds. “Curriculum making” at a teacher level, they argue, is a new invention that hasn’t worked.

“I’m a third-generation educator, and my mom didn’t create curriculum. My grandmother didn’t create curriculum,” says JanaBeth Francis, assistant superintendent of teaching and learning for the Daviess County Public Schools in Owensboro, Kentucky.

“My mom and my grandmother used textbooks to teach. So somewhere between my mom and myself, we got this notion that the teacher’s job was to create curriculum.”

Lesson planning and curriculum

Of course, there are several definitions of what it means for lessons to be “scripted”. Sometimes, it means an actual script that teachers follow, with it directing them exactly what to say to pupils at certain points: “Now turn to your partner and answer this question.”

But sometimes, a script refers to a general outline of what material teachers are to cover each day or each week.

While the two examples are wildly different, both are seen as “scripting” in the US because what many teachers have been doing over the past 20 years is so different. Research shows that, often, teachers create each day’s lesson themselves, whether from scratch or by pulling together different materials.

Eighty per cent of American teachers surveyed in the 2022 RAND American Educator Panel, for example, said they developed class material on their own - and nearly all the surveyed teachers said they often rely on online resources such as Google and Teachers Pay Teachers to find materials to use in class.

Researcher Morgan Polikoff at the University of Southern California’s Rossier School of Education says that’s because creating your own lessons is “ingrained in the American culture of teaching,” along with the concept of local control.

So, what has prompted a change from this?

Changes to teacher workload

Workload and a shifting perception of the teacher’s role are widely cited drivers.

There is plenty of research showing that US teachers are doing a lot of extra work creating lessons - after-hours time that might be connected to the high burnout rate that American teachers experience.

The RAND survey revealed that the average teacher spends 12 hours a week building lessons outside of work hours, which teachers find unsustainable. Scripting essentially takes a lot of that work away.

Advocates for scripting also point out that teachers aren’t trained to create curricula and lessons, and there is a growing sense that they should not be doing those things.

Francis has been instrumental in bringing more structured, scripted curricula into the Daviess County schools. She says a teacher’s work is about responding to pupils through teaching, assessment and feedback.

“The teacher’s role is about using the curriculum - and when I use the word ‘curriculum’, I mean all the resources. The teacher’s role is about thinking about their current students and the resources they have, and then merging the pedagogy to say, ‘how do I teach that in a way students are going to learn?’ It’s not about creating the resources.”

Support for new teachers

Alongside these two factors, other experts theorise that handing teachers an entire curriculum is seen as a way to “teacher-proof” education, solving the problem of “bad apple” teachers. American charter schools, for example, which often employ younger, less experienced teachers, have traditionally relied more on scripted curricula.

Rather than professionalising the teacher workforce, says Brown University education economist professor Matthew Kraft, a curriculum that shows teachers exactly what to say has been viewed as a faster, and perhaps cheaper, solution.

However, Kraft argues that the end result has been less job satisfaction for some teachers.

“This erosion of autonomy has contributed in part to teacher shortages,” he argues.

Teacher retention issues

Teacher shortages, while often confined to certain areas or subjects, have become a big problem: Kraft’s research has shown that nearly 40 per cent of districts had at least one unfilled teacher position at the beginning of the last school year.

Relatedly, the job satisfaction for American teachers, Kraft and researcher Melissa Arnold Lyon wrote in a recent paper, is at its lowest point in 50 years, and state-issued teacher licensures have declined from 280,000 in 2001 to just 210,000 in 2022.

Of course, if teachers are teaching out of subject to cover these gaps, then the case for scripting those lessons is strong to ensure the right content is delivered and to help those out-of-subject teachers - something that is driving a shift to scripting in England.

The idea of a minimal threshold of quality through scripting that the charter schools are pushing is also popular among some multi-academy trusts in England.

Similar arguments to those made by Kraft in relation to the US have been made in England, too: that eroding autonomy leads to a lack of professional pride and people leaving the profession.

‘The teacher’s role is about thinking about the resources - it’s not about creating the resources’

When faced with that criticism, the counterargument from scripting advocates in the US is that there is a growing amount of research suggesting it boosts academic outcomes.

The US is experiencing a big shift towards the science of learning. Cognitive load theory, Rosenshine’s Principles of Instruction, the evidence around retrieval practice and much else in the movement suggest that sequencing knowledge and teaching in prescriptive ways leads to better results for pupils.

As such, a uniform adoption of the best guess at optimal lesson structure and content from the evidence available has become the “script” for lessons.

The adoption of such “scripts” has been a key piece of the academic improvement happening over the past decade in some of the US’ poorest states, notably in reading and math.

Reading scores in the US

Nearly all the states that have seen reading scores improve recently - including Mississippi, Louisiana, Tennessee and Alabama - have changed state law to encourage districts to choose from approved lists of HQIM.

Consensus has been growing around the use of these academic materials based largely on The New Teacher Project 2018 report The Opportunity Myth, with research showing that pupils across the nation, especially ones who came from disadvantaged backgrounds, weren’t completing academic work anywhere near grade level on a regular basis.

“Ten years ago I’d go into a classroom with a principal, observe instruction, and I would point out the fact that generally what we were seeing was two or three grade levels off the mark,” says Jared Myracle, executive director of literacy for Memphis-Shelby County Schools in Memphis, Tennessee.

“There would always be an excuse: ‘Oh, they’re probably just reviewing.’ Then we’d go into the second, the third classroom - same thing. The principal’s light bulb would go off. ‘None of my teachers are actually teaching the depth of the grade level standards. What do we do?’”

Contested research?

Ensuring every teacher was using HQIMs meant classrooms in the same building were going to be learning the same things, as well as holding pupils to grade-level standards laid out in the national Common Core State Standards.

Not all the research around scripting is positive, however: Tes columnist Christian Bokhove, for example, has highlighted mixed results from a study of Engelmann’s direct instruction in England. He has also raised concerns about the evidence base for Rosenshine’s work.

Teacher and writer Mark Enser, meanwhile, has raised the issue of poorly implemented cognitive science findings, for example, with retrieval practice.

So, there are multiple factors driving the shift to scripting in the US, and all are complex. But advocates say that while the evidence can and should be debated, the argument that teacher autonomy is under threat should not be a factor in whether scripting becomes even more widely accepted: they argue that scripting is actually empowering for teachers.

The ‘stolen autonomy’ argument

For example, advocates say the states that have been most successful with implementing HQIM have invested heavily in showing teachers how to use them through professional learning time. The training helps keep the delicate balance between teachers keeping their professionalism and ensuring a uniform quality, researchers say.

“Louisiana has built a system that honours teacher expertise while providing the support of high-quality curriculum,” wrote Louisiana-based educational consultant Rod Naquin.

The state, which once held last place in academic achievement, achieved this through training and elevating teacher leaders, both in how to teach the content as well as helping develop the materials themselves, Naquin says.

Myracle says he was involved in helping the state of Florida get high-quality materials into teachers’ hands before they were in classrooms, while they were still in training, and he agrees that the “stolen autonomy” argument is a weak one.

He bristles at the idea that providing a curriculum and showing teachers how to use it is a “script” that teachers can never deviate from.

Empowerment through ‘intellectual prep’

“It’s a more efficient process to have schools collectively select something that is palatable to them, that we know is high quality,” Myracle says.

“And then, of course, teachers are going to make slight little tweaks and edits to fit their personality and style. But that gets us a lot closer to realising the expectation of the standards than trying to train a million curriculum writers.”

“When people say it removes teachers’ autonomy, my comeback is: the most creative people that we know rely on scripts. Actors, singers! They do some ad-libbing, but someone else, generally speaking, has written the words on the page.”

‘If you don’t know how to establish routines, if you don’t know how to keep a pace, a curriculum is not a magic bullet’

Similarly, Francis says that while some may instinctively react negatively to the idea of “intellectual prep” as laid out at the start of this article, it is actually hugely empowering for teachers.

“Intellectual prep is about taking all that information that you have gathered and then coming together, talking with your colleagues and saying: ‘how do we create the best learning experience for the students within the context of the material we have?’” she says.

“If I’m an experienced teacher, I bring some information that maybe a brand-new teacher won’t.”

Frederick County school leaders argue that the level of specificity in lesson preparation has resulted in steadily improving test scores since they adopted the practice, along with a host of other evidence-based practices like teacher coaching and training. Score increases have been especially significant for low-income pupils, as well as Black and Hispanic pupils.

Lack of flexibility

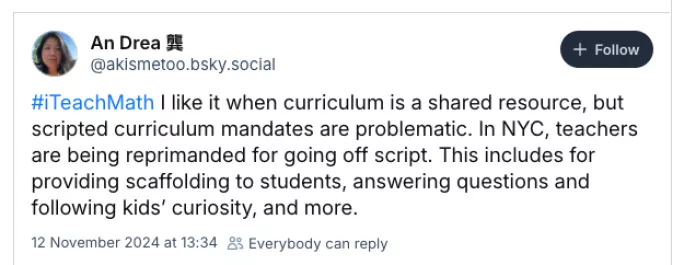

However, despite these positive case studies, not all teachers are on board with scripting. Teachers on social media complain about the downsides of scripted curriculum - like the below teacher in New York City, where there have been several reports that teachers aren’t allowed to deviate from the city’s new math curriculum:

A story in the US magazine Education Week reports that New York City’s new restrictions on teaching outside the mandated materials mean “teachers don’t have the flexibility they need to differentiate for kids coming into class with varied abilities”, referring directly to the heavily scripted nature of the materials’ lessons.

Workload wins out

But there are also plenty of teachers who find structured materials a relief and no threat to their autonomy - and their number is growing. A key part of that is workload: if anything is going to sustain the gains scripting has made in the US and increase those further, it will likely be the time it is giving back to teachers.

As 2nd grade teacher Abby Boruff, in Des Moines, Iowa, says: having a curriculum has meant that she works fewer hours, and can concentrate more on what matters, like whether pupils are learning.

“There are layers to it because I don’t think it’s as easy to say as, like, ‘here’s a curriculum’,” she says.

“If you don’t know how to set up a classroom, if you don’t know how to establish routines, if you don’t know how to keep a pace and a lesson - it’s not a magic bullet.”

“But now I can look through my progress monitoring data more clearly, I’m able to analyse that a lot more. I also just don’t work as much now. I don’t work 65 hours a week or 70 hours a week any more because I don’t have to.”

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

topics in this article