The Department for Education has been telling fibs.

In February 2017 the Commons Education Select Committee concluded its inquiry into the shortage of teachers in England, with the then committee chair, Neil Carmichael, warning that: “The situation is very, very challenging… The government must act or we will find ourselves in a real crisis.”

Never fear, the Department for Education replied serenely: “Overall teacher retention rates have remained broadly stable for the past 20 years.” Nothing to see here, move along. The select committee dutifully included the department’s claim in its final report.

The DfE must have been delighted with this outcome, and decided to keep repeating the claim at every opportunity. Since then, the ”broadly stable” claim has been quoted or reproduced by the BBC, the Guardian, the Mail, the Telegraph, the Sun, Tes, Schools Week, the Huffington Post, the Yorkshire Post and the Birmingham Post. More seriously, it was repeated by Justine Greening in a statement to the House of Commons in December 2017.

The government’s tall tale

The trouble is, it’s a whopping great fib.

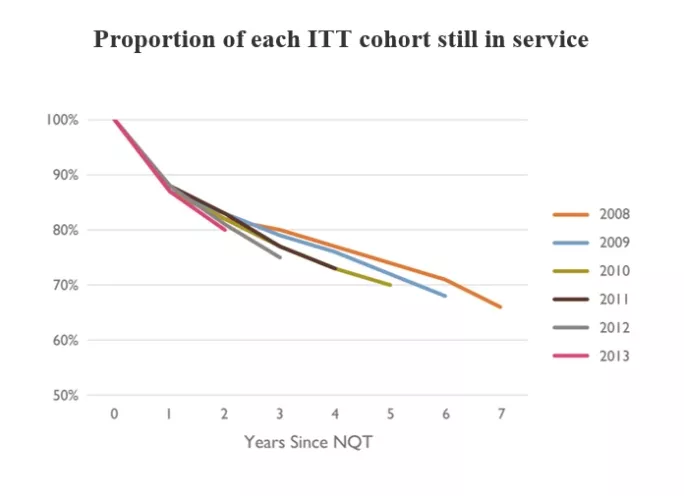

The chart below shows what has happened to retention for each cohort of newly qualified teachers since 2008. On the left, we see each cohort of trainees entering the profession. Then, as we move right across the graph, we see retention dropping off as the cohort progress through one, two and more years in the profession. Since 2009, each new cohort has been going south quicker than the last. Retention is dropping.

So how does the DfE justify the tall tale it has been telling? Its response to the select committee references its own analysis, which finds that: “The percentage of teachers that are still in post one year after qualifying and starting a job has remained static at 87 per cent.” A glance back at the graph above shows that this is technically true, though so far from being the whole truth as to be straightforwardly misleading. It certainly doesn’t justify the sweeping statement that retention is “stable”.

But perhaps the DfE can get off the hook by relying on the weasel word ”broadly” in its claim that retention is “broadly stable”. In the same report, it claims that “the percentage of teachers that were still in post three years after qualifying and entering service was 75 per cent, a small decrease on the previous year’s figure of 77 per cent”.

But that’s not really true either. I calculated what would have happened if retention rates had been frozen at their 2009 levels, so that every line in the graph above looked like the orange one. In short, we would have had an additional 4,398 teachers working in our schools by now. To give a sense of scale, this is more than double the current nationwide shortage of English Baccalaureate teachers at secondary level.

Teacher retention is not stable. It’s not even broadly stable. Admitting you have a problem is the first step towards solving it, so the DfE should stop using its big retention fib - and people should stop believing it.

Sam Sims is a research fellow at Education Datalab and tweets at @sam_sims_

Want to keep up with the latest education news and opinion? Follow Tes on Twitter and like Tes on Facebook