- Home

- Eight key pieces of research for teachers

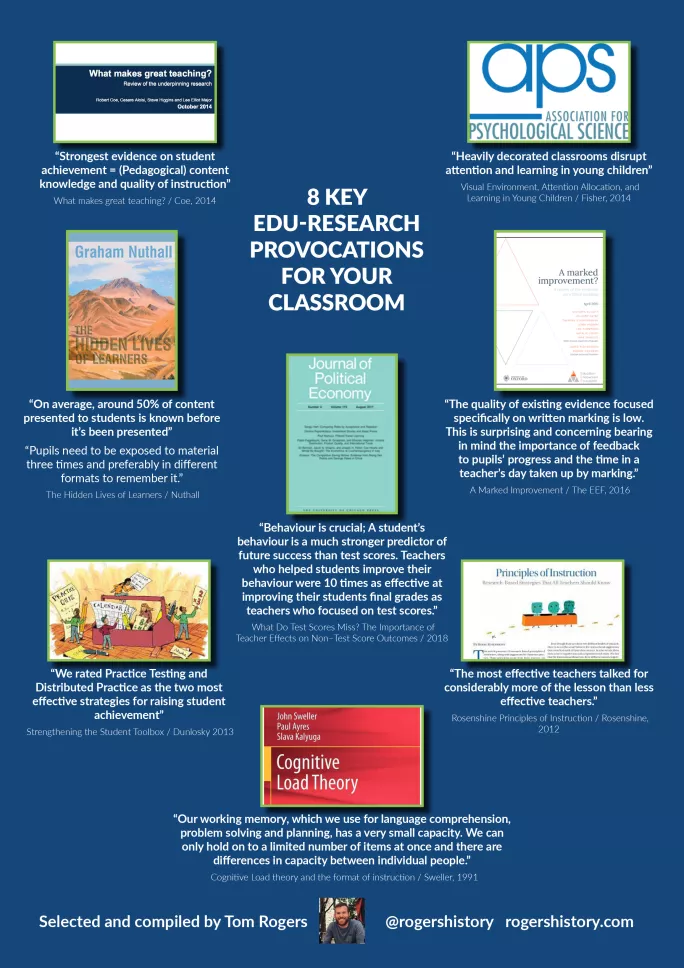

Eight key pieces of research for teachers

Here are eight key pieces of research that I’ve come across in the last few years, which have made me re-evaluate beliefs I’ve had about teaching and learning. I’ll reflect on how below.

1. Student achievement

“Strongest evidence on student achievement = (pedagogical) content knowledge and quality of instruction.”

I’ve returned to this report time and time again since 2014. I led an Inset session in April and asked staff to predict (before looking at the report) which of six teacher traits they expected would have the strongest evidence behind them for student achievement.

The room was divided. The results of this extensive study are as interesting as they are significant for professional development in schools.

2. Classroom decor

“Heavily decorated classrooms disrupt attention and learning in young children.”

Prescribed knowledge told me that walls should be full to the brim with glossy shiny brilliance. But this study, and several later ones such as this research paper published in the December 2018 edition of the Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, has made me question the impact of displays in classrooms. I never truly considered the distraction displays could cause to learners. I certainly do now.

3. Lesson content

“On average, around 50 per cent of content presented to students is known before it has been presented.”

In how many lessons in my career have I presumed the students didn’t know something? I’ll hold my hands up and say: plenty.

Yes, sometimes I’ll have dedicated time to diagnostic quizzing and questioning at the start of a unit or topic, but how often have I truly acted upon that for each student there?

Sometimes, I would simply forget to go through that fact-finding process with students. Being aware of this research has made me think again about how crucial establishing prior knowledge is and about how regularly I should do it.

4. Practice

“We rated practice testing and distributed practice as the two most effective strategies for raising student achievement.”

I always saw the value of revisiting content with students at regular intervals, whether that be in consecutive lessons or “spaced” over weeks or a term or a year. Nevertheless, research studies like this one really bring home the message of how high the impact of “retrieval practice” and “spaced learning” is.

Yes, we can use new-fangled labels, but we are essentially talking about systems of reviewing learning with students so it’s embedded into long-term memory - that’s the ambition. Of course, that’s easier said than done.

5. Cognitive load theory

“Cognitive load theory is a theory about learning built on the premise that, since the brain can only do so many things at once, we should be intentional about what we ask it to do.”

This one has wide implications. Although I grasp the concept, the implications for the classroom and pedagogy are extensive. The Australian guidance document Cognitive load theory in practice gives an excellent summary of what it means for teachers, neatly summarised as:

Strategy 1: Tailor lessons according to students’ existing knowledge and skills.

Strategy 2: Use lots of worked examples to teach students new content and skills.

Strategy 3: Gradually increase independent problem-solving as students become more proficient.

Strategy 4: Cut out inessential information.

Strategy 5: Present all essential information together.

Strategy 6: Simplify complex information by presenting it both orally and visually.

6. Written marking

“The quality of existing evidence focused specifically on written marking is low. This is surprising and concerning, bearing in mind the importance of feedback to pupils’ progress and the time in a teacher’s day taken up by marking.”

Back in 2007, when I started my teacher training, if someone had said, “Let’s stop marking so much and promote feedback (particularly verbal) as much as possible,” they surely would have been scoffed at.

This would not have been because teachers didn’t believe it: I think they’ve always known it. But Ofsted, the government and many senior figures in education truly believed the hype around quadruple written exchanges between teachers and students via green ink.

Since then, we’ve seen a shift, to the point now where many schools are fully embracing the “feedback not marking” agenda. The Education Endowment Foundation’s highlighting of the gap in evidence for the impact of written marking has helped.

Teachers and students are seeing the benefits. Matt Pinkett, an English teacher, tweeted last week that he hadn’t marked a book all year but students had achieved their best results. In my current teaching and learning role in school, I’m pushing the idea that it’s always about the substance rather than the superficial. The evidence is in the learning.

Recently, I read an excellent case study from a secondary school in Walsall. Their marking and feedback policy was built around asking students two simple questions:

1. What are you doing well in this subject?

2. What do you need to do to improve in this subject?

If students could answer these two questions, in subject-specific detail, then they’d have benefited from effective feedback. Nowhere do they state anything about written comments.

7. Teacher talk

“The most effective teachers talked for considerably more of the lesson than less-effective teachers.”

At the start of my career, it was common to hear things like: “Teachers shouldn’t be talking for more than 10 per cent of any lesson.” Barak Rosenshine’s paper on the impact of effective instruction in class has really shone a light on such theories.

Mark Enser wrote last week for Tes about dispelling the myth that too much teacher talk is bad, by calling on the profession to focus on better teacher talk rather than less of it.

I echo this call. As I roll into my 13th year as a classroom teacher, I realise more and more that good explanations require time. Yes, I’m still a great believer that students need variety and structure, but I will no longer stop explaining something properly because it’s “time for the plenary”.

8. Behaviour management

“Behaviour is crucial: a student’s behaviour is a much stronger predictor of future success than test scores. Teachers who helped students improve their behaviour were 10 times as effective at improving their students’ final grades as teachers who focused on test scores.”

For me, this report confirms what I’ve always believed: the behaviour of students within a school and classroom is more important to educational achievement than any pedagogical development.

Schools and individual teachers who intervene, challenge and focus on behaviour first will see students achieve higher in exams. Approaches to student behaviour can vary, but building a positive attitude, culture and ethos is surely key to major improvements in academic achievement.

Tom Rogers is a teacher who runs rogershistory.com and tweets @RogersHistory

Keep reading for just £1 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £1 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters