- Home

- How to develop habits of creative thinking

How to develop habits of creative thinking

It’s 20 years since the landmark National Advisory Committee on Creative and Cultural Education report All Our Futures: Creativity, culture & education was published. The report offered a simple definition of creativity: “Imaginative activity fashioned so as to produce outcomes that are both original and of value.”

It made clear that creativity was relevant in every subject of the school curriculum. However, it did not offer much practical advice as to how teachers might embed creativity in their teaching.

Advancing the creative agenda

Twenty years on, we are much clearer about the cultural and pedagogical changes necessary for creativity to be embedded in schools. In fact, 2019 is proving to be a key milestone in advancing the agenda of creativity.

The findings from a major 11-country study of creativity by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development’s Centre for Educational Research and Innovation will be published later in the year, and decisions will be taken by countries across the world about whether they will participate in the Pisa 2021 test of creative thinking.

Closer to home, Wales has launched a new curriculum that gives a central place to creativity and in September, the Durham Commission on Creativity and Education will launch its final report.

And, finally, the new Ofsted framework comes into force this year. Not traditionally associated with creativity, Ofsted’s encouragement to schools to think more widely about curriculum and to document their intent, implementation and impact is actually an opportunity to reframe the role of creativity in schools.

Learned skills

It was good to see a recent piece by Stellan Ohlsson and Pim Pollen in Tes, arguing that creativity is a series of dispositions, rather than an ability or a set of processes. The authors argue that this approach is under-explored in schools.

At the Centre for Real-World Learning (CRL), we agree. Knowledge and context matter hugely. There is a range of creative skills that can be learned and practised in different situations.

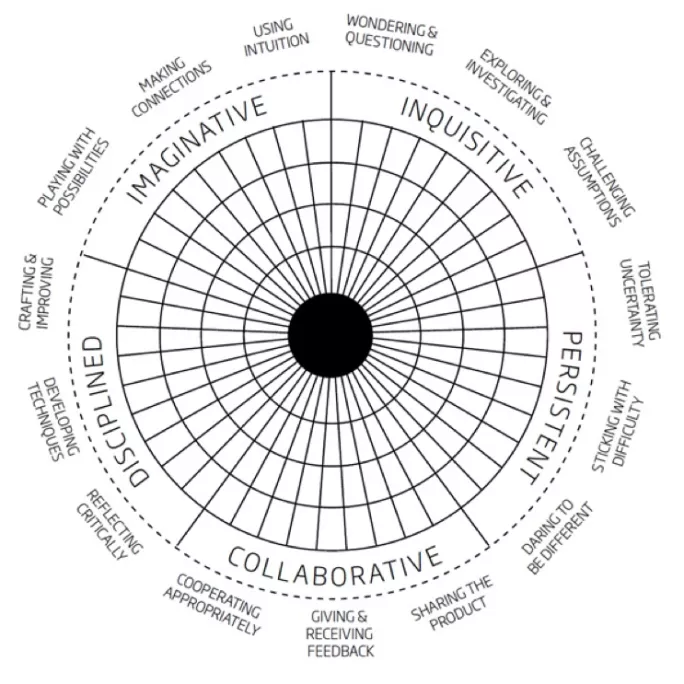

But, ultimately, human creativity is about developing habits of creative thinking. Our five-dimensional model for creativity in schools, developed with the OECD, is widely used across the world from Australia to Chile, Norway to Thailand, the Netherlands to England. In Wales, more than 500 schools, with the Arts Council of Wales, the Welsh government and Creativity, Culture and Education, use our five habits model to explore ways of embedding creativity in schools.

CRL’s five habits of creativity

To be clear, these creative habits or dispositions can be learned by all children. Our model describes an approach to creativity that Anna Craft calls ”little-c creativity”: the everyday capability of coming up with ideas and filtering their value in the light of experience and context.

The ecology of creative schools

If schools are to make creativity normal, then they need to think about the culture they seek to create.

From our research, 10 key aspects of the classroom and staffroom ecology keep recurring:

- Learning is almost always framed by engaging questions which have no one right answer.

- There is space for activities that are curious, authentic, extended in length, sometimes beyond school, collaborative and reflective.

- There is the opportunity for play and experimentation.

- There is opportunity for generative thought, where ideas are greeted openly.

- There is opportunity for critical reflection in a supportive environment.

- There is respect for difference and the creativity of others.

- Creative processes are visible and valued.

- Students are actively engaged, as co-designers.

- A range of assessment practices within teaching are integrated.

- Space is left for the unexpected.

Core approaches

Our research, reinforced by the OECD’s study of the ways in which creativity can be taught and assessed, has shown that there are certain “signature pedagogies” which work well. These include the use of case studies, philosophy for children, deep questions, authentic tasks, a focus on the design process, enquiry-led teaching and deliberate practice.

Two core approaches really help: split-screen teaching and visible-thinking routines. Split-screen teaching, pioneered by my colleague Guy Claxton, reminds us of the importance of embedding creative habits in the context of a subject. For example: history + critical reflection; scientific enquiry + appropriate cooperation; writing an argument in English + challenging assumptions.

And the use of visible-thinking routines, well-documented by Harvard University’s Project Zero, is an invaluable way of moving from knowledge to dispositions. So a routine such as Think-Puzzle-Explore embeds inquisitiveness, or Think-Pair-Share-Think provides routine opportunities for challenging assumptions and giving and receiving feedback.

Later this year, the OECD will launch an app with materials for teaching and assessing creativity in schools. The Durham Commission will make recommendations for ways in which school leaders and teachers can be supported in England.

Now is the time to get determined and creative about giving all children the chance to develop their creativity at school.

Professor Bill Lucas is director of the Centre for Real-World Learning at the University of Winchester and co-chair of the strategic advisory group for the Programme for International Student Assessment’s 2021 test of creative thinking. He is the author of many books on creativity and learning including, with Ellen Spencer, Teaching Creative Thinking: Developing learners who generate ideas and can think critically. He tweets at @LucasLearn

Register with Tes and you can read two free articles every month plus you'll have access to our range of award-winning newsletters.

Keep reading with our special offer!

You’ve reached your limit of free articles this month.

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Save your favourite articles and gift them to your colleagues

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Over 200,000 archived articles

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Save your favourite articles and gift them to your colleagues

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Over 200,000 archived articles