How to get every pupil focused on learning

Share

How to get every pupil focused on learning

In the book Why Don’t Students Like School?, Professor Daniel Willingham writes that “people are naturally curious, but we are not naturally good thinkers; unless the cognitive conditions are right, we will avoid thinking”.

Given that he also reminds us that “memory is the residue of thought”, this poses something of a challenge for teachers: if we want pupils to remember what they have been taught, they need to think about it. But people avoid thinking.

What is a teacher to do?

- Quick read: Professor Willingham is an expert on how to teach reading. Read an interview with him here

The distractions of novelty

Well, we can start by not making it easy for our classes to avoid thinking by throwing endless distractions in their way.

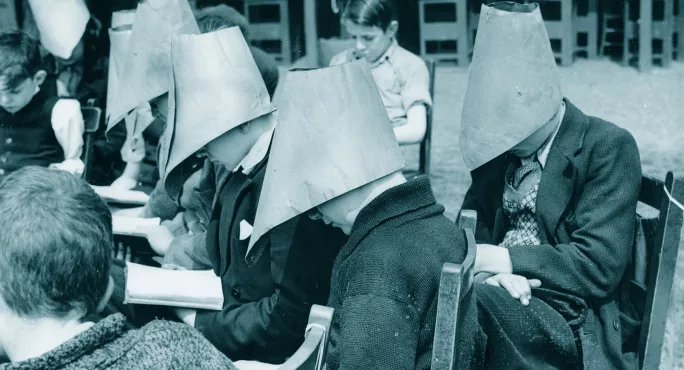

We might have interesting displays at the front of the class that catch the eye, we may allow pupils to chat about their day as they work or we could often be less than strict about a no mobile phone policy - all of these things encourage pupils to avoid the hard business of thinking about their work in favour of anything else. Our minds seek distractions and sometimes we teachers provide them.

But I would argue that a far greater problem arises when the task itself distracts from the learning.

This often happens for well-meaning reasons: we want to help make the lesson memorable. Most of my class remember a lesson from several years ago when I asked them to make a model shanty town out of cardboard boxes. Every so often, as they were building their model house, I would announce the kind of problem that might affect someone living in informal settlements and come and remove some material or flood their model with water.

The lesson was certainly memorable but the very next week they couldn’t tell me about life in shanty towns or the problems faced by people there.

The loved the lesson, but this didn’t mean the subject of the lesson had been remembered

- Quick listen: Want to know more about memory? Professors Robert and Elizabeth Bjork are world experts and spoke to the Tes Podagogy podcast

Memorable lessons

These types of lesson are all too common. They are rolled out for observations as they tick any number of boxes for pupil engagement and provide very visible signs of pupils doing things that it is (wrongly) assumed lead to learning.

One reason for this assumption is that it has been argued that we are better at recalling the source of memories linked to events (episodic memories) than we are the source of memories linked to more abstract ideas (semantic memories).

This can lead to us, falsely, believing that we need to create memorable lessons as these are the ones we remember from our own school days. They feel more effective. But they are not.

Embracing routine

Luckily, Willingham’s quote above not only highlights the problem but also provides the solution as well.

Firstly, there is the caveat: “unless the cognitive conditions are right…”. We can get these cognitive conditions right by embracing routine.

Some experienced teachers worry that their lessons are all getting stuck in a rut. Pupils come in, do the same kind of work, and then leave.

Actually, this is not a problem, but a sign you have found out what is working and you are sticking with it.

We want to reduce the undesirable distractions that prevent pupils from thinking about the content of the work. Removing the need to think about the what or why of changes to routine helps this happen.

Where do they sit? Will the books be on the table for them? Where do they write their work? What do they do if they get stuck? We want all of this to be as fluent as possible so that they only need to think about the subject they are studying.

Knowing the order

My classes know that they come in as soon as they arrive, they write the title and date and then complete the short retrieval task that is on the board. This is almost always a quiz or one slightly longer question. There will then be some sort of input of new information from me, a book, a video clip and lots of questioning; they will then apply this to answering questions. There are no complex instructions, the complexity is in the subject we are studying.

- Want to know more? Check out Doug Lemov talking about the importance of routines for learning

Another way to achieve this is to remove the distractions caused by the task. If pupils are thinking about how best to design a newspaper front page, or stick the cardboard together to make a model house, they are not thinking about the subject you are teaching (unless, of course, it is newspaper design or cardboard modelling).

This approach always raises some concern that the lesson will be less “engaging” and that pupils will be put off learning by not having access to more diverse and entertaining activities. Luckily, the solution to this is in the very first few words of Willingham’s comments: “People are naturally curious”.

Celebrate the subject

Our subjects are fascinating in themselves. The things we want pupils to learn are worth learning in their own right and don’t need cloaking behind novelty.

Starting a topic by explaining to the pupils that, by the end of the lesson, they will understand why the view outside their window looks the way it does, or why this battle happened, or why water behaves the way it does, inspires curiosity and a desire to learn the answer.

We do our pupils a disservice when we assume that they couldn’t possibly be interested in learning new things and therefore they need to be distracted from the process.

Let’s not fear getting stuck in a teaching rut. We should embrace it as an effective and efficient way to teach that enables pupils to share your love of your subject for its own sake.

Mark Enser is head of geography and research lead at Heathfield Community College in East Sussex. His first book Making Every Geography Lesson Count is out now.

- Want to read more from Mark Enser? All of his Tes articles are on his author page

Further reading:

-

Professor Dylan Wiliam on what you need to know about memory

-

Primary headteacher and blogger Clare Sealey on why retrieval practice is like a handbag

-

Four ways to tackle working memory issues

Each week, Tes produces a magazine (available in print and online to subscribers) that gives you detailed, up-to-date teaching and learning guides, analysis and advice based on the latest research. It is essential reading for the informed teacher and school leader. You can subscribe here.