Marking is hard. Marking open tasks such as essays and extended writing is particularly hard, because, unlike more closed tasks, the marker has to make difficult judgements about quality.

If the mark scheme tells you that the right answer for 34 x 58 is 1972, then you know what to do. But if the mark scheme tells you that the best types of answer for a piece of creative writing will use “original and varied vocabulary”, the judgements you have to make are more difficult.

And because marking is hard, we use mental shortcuts to make it easier. Instead of only looking at the actual quality of work a pupil has produced, we inadvertently and unconsciously use other information about the pupil to help us make our judgements. When we’re marking the work of pupils in our own class, we have a lot of information about the pupil in question, which can potentially bias our judgements.

Ethnicity bias

Perhaps the most well-explored of these biases is ethnicity. A series of studies have shown that unconscious bias creeps into teachers’ assessments of their own pupils. A study by Simon Burgess and Ellen Greaves in 2009 showed that Black Caribbean and Black African pupils were “under-assessed”: that is, that they did worse in their teacher assessments than in their tests. Indian and Chinese pupils were “over-assessed”: they did better on teacher assessments than on tests. Burgess and Greaves suggest that we carry stereotypes about the performance of different ethnic groups and these unconsciously influence our judgements of members of those groups.

A study by Tammie Campbell of the Institute of Education found something similar with gender bias. Boys were “over-assessed” in maths, while girls were “over-assessed” in reading. Again, stereotypes about boys being good at maths and girls good at reading appear to influence teachers’ judgements.

Externally-marked tests solve some of these problems because markers don’t know anything about the pupils or their backgrounds. Even with externally marked tests, though, problems can creep in. For example, when external markers know the names of the candidate, they can be biased in favour of more “attractive” first names.

Of course, it is fairly straightforward to eliminate such bias by anonymising scripts.

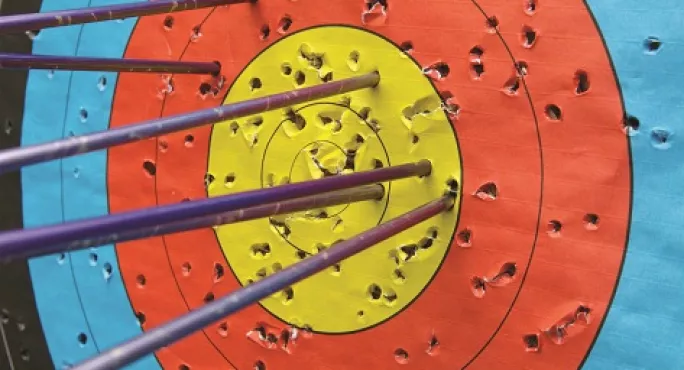

The contrast effect

It’s harder to eliminate the bias caused by the contrast effect. This is when an examiner is influenced by the standards of the scripts they’ve just marked. For example, if they see an average script after seeing a series of really good ones, they will tend to mark the average script down. If they see an average script after seeing a series of poor scripts, they’ll mark the average script up. One way to try and get around this is to read a series of scripts before starting to mark.

Yet another persistent and related bias is the “halo effect”. When you mark an exam paper consisting of a series of questions, it’s easy to let good or bad performance on the first question influence your judgement of the later questions. First impressions can lead to bias. Exam boards have reduced this problem by introducing electronic marking, which allows exam papers to be split into individual questions and distributed by question rather than by paper.

So, if you’re worried about the accuracy of your marking, you’re probably right to be. But you are also not alone: everyone is struggling with a similar problem.

Daisy Christodoulou is director of education at No More Marking and the author of Making Good Progress? and Seven Myths about Education. She tweets @daisychristo

Want to keep up with the latest education news and opinion? Follow Tes on Twitter and Instagram, and like Tes on Facebook