- Home

- Long read: Greening - ‘I have no regrets’

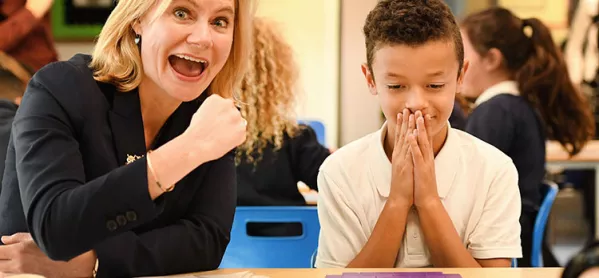

Long read: Greening - ‘I have no regrets’

Justine Greening may no longer be in government, but she’s still got her nose to the grindstone. When Tes meets the former education secretary, she’s wading through the hundreds of emails she has received from constituents that week.

Greening says the weight of correspondence has grown in recent years – something she attributes to Brexit galvanising people’s interest in politics. And since she's defending a narrow majority in Putney of just 1,554 votes, she can’t afford to slack off.

But while she’s hardly got her feet up, it’s quite a change to go from secretary of state of one of Whitehall’s most important departments – with 10,000 civil servants at her beck and call – to life as a backbench MP.

“I had been a minister for nearly eight years, so yes, it is a very different day now,” she smiles.

The manner of Greening’s departure from the Department for Education was not of her choosing. After 18 months in the job, she resigned in January after refusing to take the role of work and pensions secretary in Theresa May’s botched cabinet reshuffle.

Her 544-day tenure as education secretary was relatively short in historic terms (the average is 868 days). But Greening is clear about what she wants her legacy to be. Asked to name her proudest achievement, she immediately replies: “It has to be pulling together the social mobility action plan.”

Published in December 2017, the plan set out a plethora of measures to improve equality of opportunity. New free schools were to be targeted at the most disadvantaged areas, support for teachers in challenging schools would be beefed up and resources made available to close the “word gap” in the early years.

With Greening leaving government just weeks before the plan was published, does she fear it could now be a dead letter? “I certainly hope not,” she says. “I felt it was well received, and also it was a very structured piece of work.”

Many people in the education sector could find little to disagree with in the 41-page document, which packaged together a host of existing DfE ideas and initiatives, as well as introducing some new policies. But critics questioned whether the piecemeal reforms set out in the plan would have sufficient clout to break decades of ingrained social immobility. Where was the government’s big bazooka?

Greening responds by highlighting the broad support that the plan commanded. “Some people might say [that] was unusual for a government policy document – and a good thing if you want it to actually change stuff on the ground,” she retorts.

And she doesn’t accept the criticism that the plan was too bitty. “Life is complex and if you want to change the real world then you have to have a plan that deals with that complexity and doesn’t pretend it doesn’t exist,” she says bluntly. “There is no silver bullet, as much as people may find it convenient to think there is on social mobility…Simplistic solutions never, in the end, bring long-term change.”

Grammars row

“Life is complex”. “There is no silver bullet”. “Simplistic solutions” don’t work. Those words could be viewed as a stinging rebuke to some of the policies that Downing Street tried to foist onto Greening during her time in office.

Top of the list was the roll-out of new grammar schools. The policy was cooked up by the prime minister’s former joint chief of staff, Nick Timothy, and Greening only ever seemed to give it lukewarm support. Fortunately for her, she didn’t have to see the policy through, after the Conservatives’ squandering of their parliamentary majority meant May lacked the MP numbers to change the law.

But does Greening regret that her time heading up education was overshadowed by the row over grammar schools? A long silence follows while she carefully chooses her words. “I don’t think I’ve got anything particularly new to say,” she replies.

She does claim the green paper that launched the ill-fated policy did contain some positives, though. “I felt it was a good chance to really look at how we could make grammars more accessible for kids from the most disadvantaged backgrounds…I felt like the debate did move that on in a positive way.”

And when the DfE finally published its response to the green paper in May (after Tes spoke to Greening), it stated that taking on more children from disadvantaged backgrounds would be a precondition for grammars wanting to expand.

Unflashy pragmatism

She might have the freedom of the backbenches, but Greening clearly doesn’t want to burn her bridges with the government and the right wing of the Conservative Party by settling old scores. One gets the sense that she’s picking her battles and taking a stand on issues for which she feels she can best exert her influence.

In a recent interview with the Times, she stepped into the Brexit debate, calling on the government to keep its options open on the customs union and to not let the Brexiteers call the shots.

In education, she chose to speak out against plans to abolish the faith school cap for free schools – something that Greening said would not help schools “bring children together” and prepare them for life in “modern Britain”. The DfE subsequently announced that it would retain the cap, at least in name – an indication, perhaps, of the quiet effectiveness of Greening’s intervention.

The scepticism with which Greening treats eye-catching policies – scrapping the faith school cap, rolling out new grammars – is symptomatic of the unflashy pragmatism that defined her tenure as secretary of state. Asked whether the education debate in England has become too polarised, characterised by its perennial skirmishes between “traditionalists” and “progressives”, she says: “Nothing is ever all good or bad.”

“I always understand why people want to make things black and white – because often it makes it easier to communicate with people what you’re trying to accomplish. But I don’t think that should be at the expense of smart policymaking informed by evidence.”

This pragmatism extended to her relationship with the education unions. When Greening resigned, the spectacle of union bosses lining up to mourn the exit of a Conservative education minister was striking.

“Although we had many disagreements, Greening made as successful a fist of her role as was possible under very difficult circumstances,” commented Mary Bousted, the joint general secretary of the National Education Union.

Was Greening surprised by the reaction? “I felt that I had hopefully built up a constructive working relationship with the profession and with the unions,” she says. “I think we recognised that there were some areas where there would be disagreement, but crucially, that should never get in the way of us working together on areas where we had a common cause.”

In the days leading up to the cabinet reshuffle, anonymous briefings appeared in the media claiming that Greening’s job was in peril precisely because she’d got too close to the unions. Addressing that claim, she just says: “I think you get further working with people rather than simply finding a fight to have for the sake of it.”

It’s a far cry from Michael Gove’s crusade against “the blob”.

Still shaping the agenda

Leaving the DfE hasn’t stopped Greening from banging the drum for social mobility. In March, she launched a social mobility “pledge” in Parliament that commits employers to adopting open-recruitment practices, and working with schools to provide careers advice and work-experience opportunities for people from disadvantaged backgrounds.

“Nobody had to do anything on that, or agree with it, but I managed to get the Confederation of British Industries supporting it, the British Chambers of Commerce, the Federation of Small Businesses,” she says proudly.

And Greening has shown that she can still shape the national education agenda. Her call for employers to adopt “contextual recruitment” practices – which could mean a candidate from a challenging school getting a job before an Old Etonian with the same grades – generated both newspaper headlines and fierce debate.

“I’m actually really enjoying the challenge of being out of government but still using the role that I’ve got to make a difference,” she says.

So what does the future hold for Greening? Her name has been placed in the frame for a tilt at the London mayoralty, as the Conservative candidate in 2020. Asked whether she would be interested, she does not give an outright denial, but says: “Leaving government was not about opportunities for me, it was about opportunities for young people.”

Her answer when asked whether she would have a second stint as education secretary is less equivocal: “I said it was the best job in government, so I loved doing it and it would be a privilege to have the chance to serve again."

Whenever and wherever Greening next pops up in government, one senses that education and social mobility will be an important part of it.

She has stated what her proudest achievement was, but what about her biggest regret?

“Oh, I don’t think I do particularly have regrets,” she replies breezily. “I went into that role aiming to use every single day in the job to try to achieve as much as I can for the generation of schoolchildren and young people in the state system.

“I got to the end of my time and I had bust a gut. I didn’t feel like I wasted a single moment, and I think that’s all you can really have asked.”

Keep reading for just £1 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £1 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters