- Home

- Number of colleges with £9K tuition fees doubles

Number of colleges with £9K tuition fees doubles

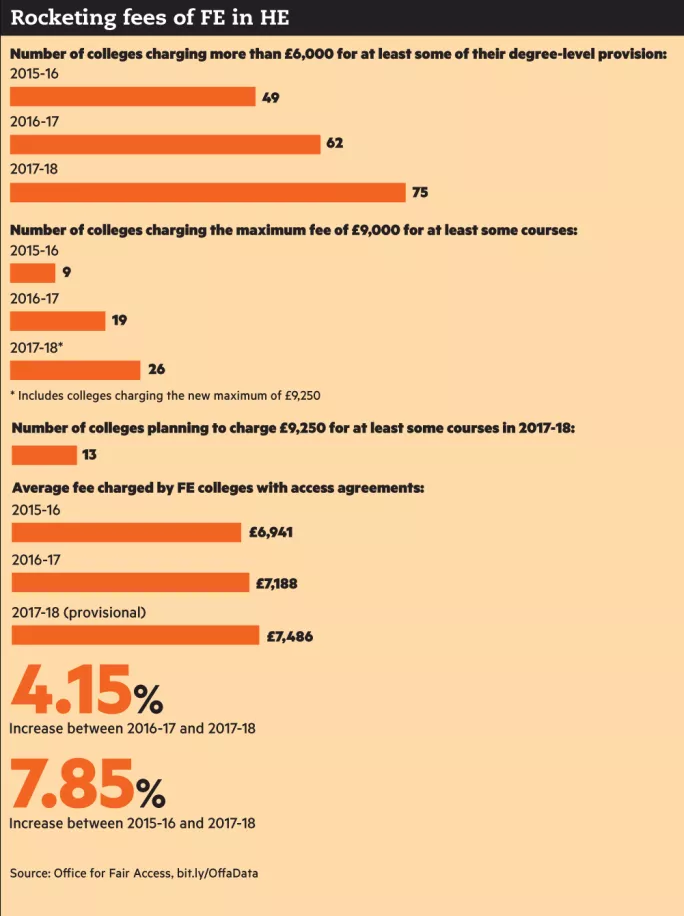

The number of further education colleges charging the highest possible tuition fees for undergraduate degrees has doubled in a year, TES can reveal, and more than a dozen institutions plan to raise their fees even higher next year.

Figures obtained from the Office for Fair Access (Offa) show that in 2015-16, a total of nine FE colleges charged the maximum fee for at least some of their courses. However, that number is set to rocket to 19 in this academic year. The cap is expected to be raised to £9,250 in 2017-18, with 13 colleges planning to charge at this level and another 13 intending to charge £9,000.

The data, which includes only those colleges charging more than £6,000 per year for degree provision, also shows that the average fee is set to rise from £6,941 last year to £7,188 this year and £7,486 next year - an increase of almost 8 per cent in two years.

Institutions charging more than £6,000 for courses are required to establish an access agreement with Offa. Figures for 2016-17 reveal that significantly more colleges are charging above that threshold than last year, with the number rising from 49 to 62 - it is set to rise further to 75 next year.

About 250 colleges offer degrees, according to the Association of Colleges (AoC). The first FE institutions to bring in the highest fees were Leeds City College, the Manchester College and Plymouth College of Art, which were given permission to charge at the same level as the most expensive universities by Offa in 2012.

Recouping costs

As colleges attempt to recoup costs after six years of cuts to public funding, student representatives believe that the increase in the number of FE colleges charging the top fees could have a damaging effect on the diversity of learners studying at higher levels.

Shakira Martin, NUS vice-president for FE, said: “Higher education in colleges is not a ‘cheaper option’ but provides a far more accessible option to learners who cannot access university. These courses offer a lifeline for learners who need to study more flexible, localised courses and find university education inaccessible.”

These courses offer a lifeline for learners who need to study more flexible, localised courses and find university education inaccessible

Many FE in HE learners were older with dependents, had learning difficulties or were more likely to be debt-averse as they were retraining for another vocation, she added.

However, Nick Davy, HE policy manager at the AoC, stressed that three-quarters of colleges still charged below £6,000 for all their courses.

Among the reasons for allowing fees to reach the top level were the higher costs of running some courses, such as social work and land-based provision. There were also a number of colleges where local competitor universities had led to pressure on colleges to charge similar fees. And inflation had played a part, he stressed.

“Some of the big colleges are in areas where there is much more competition with universities, and what colleges have to be aware of is that sometimes, in a market situation, if you are charging a low price, that can signal for some applicants that what you are offering is low quality,” he said.

Colleges also wanted to ensure they offered the full university experience, which could increase the price, he added.

However, Mr Davy explained that many colleges saw offering opportunities to learners from disadvantaged communities as the core purpose of their provision, and they were therefore determined to keep fees low. “A lot of that provision is in areas with traditionally low HE participation rates,” he said.

Sector experts agreed that the changes were down to competitive pressures and changes in the HE landscape. Nick Hillman, director of the Higher Education Policy Institute (Hepi), said he was not surprised by the shift.

Competitive pressure

“First, because the last few years have shown that entering higher education is not a particularly price-sensitive business - at least for many students,” Mr Hillman said. “Second, the new and extra focus that traditional universities are now putting on the quality of teaching and learning, under pressure from government, has changed the environment.

“It has become harder for FE colleges to argue that their students will get more intensive support than what is on offer elsewhere. So they have to run to a standstill. There is the competitive pressure from alternative providers, too, which may be a third factor.”

Jonathan Simons, head of the education unit at thinktank Policy Exchange, said it made sense that a college could charge the same as a university. “There is a cheaper alternative, because they also offer other courses as level 4 and 5 vocational courses.

“So I’m less bothered by more charging £9,000 - especially if they offer loans for tuition and maintenance - and more bothered by the disappearance of level 4 and 5 courses.

“The loss of such courses is bad for students, bad for the Exchequer, and arguably bad for employers, which could otherwise have found a number of employees who have achieved a more work-focused qualification in less time than it takes to do a degree.”

Keep reading for just £1 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £1 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters