Read all about it

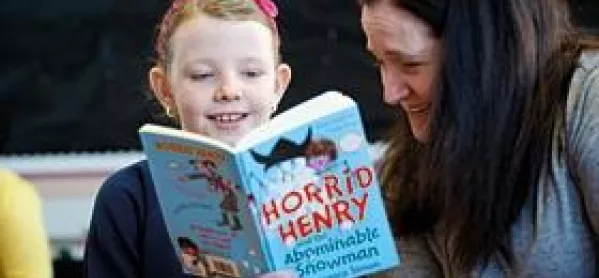

Children who can’t read have poor life chances. Even reluctance to read is a barrier to success, according to recent research by the University of Oxford which shows that reading for pleasure is the only youthful activity linked to better job prospects. So a University of Strathclyde project in Glasgow’s east end is literally changing lives.

“I thought reading was a waste of time,” says Jamie, one of 10 P4 children at Balornock Primary being intensively tutored by Strathclyde student teachers since the start of this session. “You could do more stuff than reading.

“But now I like it. It’s easier to read a book than go on the computer. I read about football and I like stories with chapters, like Beast Quest. That’s about a wee guy who’s trying to defeat big monsters.”

The origins of the Balornock project lie in literacy work that Strathclyde’s Sue Ellis and Balornock’s depute head, Christine McCandlish, had been doing together, says the latter: “I’ve worked with Sue for a number of years and she has delivered CPD sessions to our teachers. She is passionate about children’s literacy.

“That partnership between schools and universities is important, I believe. It means we teachers get access to the skills and expertise of university staff and to the latest research.”

Reading is a complex learning activity, according to that research, and there is no magic pill for problems, she says. “There is a lot of media hype about phonics, for instance. Now that is important but it’s not a panacea. I had a group of reluctant readers who had strong input from a phonics approach, but it did not lead to success. The children were just doing more of what hadn’t helped already.

“Instead, we need to be trying a wide range of approaches, because each child has a different way of learning. You have to be reflective. You have to look at what works.”

The structure of the Balornock literacy clinic is that Strathclyde student teachers come to the school to deliver half-an-hour’s one-to-one tuition every week, in a little classroom well stocked with books and reading games. Four students are assigned to each of 10 P4 children, selected as likely to benefit. So each child gets two hours’ tuition a week.

“When we asked our students who would like to volunteer to take part in this project, in addition to all the work they were already doing, we thought we’d maybe get half a dozen,” says Strathclyde lecturer Jane Thomson. “We got 44.”

The reason is that this is a genuine partnership that benefits both sides, says third-year BEd student April Shepherd. “I have learned a lot, especially about how important interest is to learning. You hear about it in lectures. But you don’t necessarily see it in a class, where you’re doing a reading scheme and it’s not their choice. Getting to work one-to- one shows how big a part capturing their interest plays in motivating children and taking them forward.”

The lessons the children are learning can be carried into whole-class teaching, believes third-year BEd student Fiona Telfer. “Maybe not to the same depth or extent. But there is no reason why once or twice a week, children can’t choose a book from the library or bring in one that interests them and read that, alongside your reading scheme.

“You can also get to know what interests them - and you can work with books on those topics.”

Enjoyment is fundamental, Mrs McCandlish says. “I’ve been focusing around the school on children reading for enjoyment and on reading mileage. Those who struggle with reading go on to read less, and get exposed to less text throughout their time at school. I want to change that in whatever way we can - one-to-one, shared reading, paired reading, talking about stories, reading games, anything that works.”

One-to-one is working for young Aiden, who is making individual letters into words on a board, guided by student teacher Gemma McGowan. “I like this book because it’s about dinosaurs,” he says.

He starts reading from Land of the Dinosaurs, slightly hesitantly but very well. ”`We are going on a magic adventure,’ said Chip. The children went t. through.”

“Well done,” Mrs McGowan says. ”. the door of the magic house.”

Aiden reads six pages aloud with obvious pleasure. “I couldn’t read as good as that before,” he says.

“We’ve been working on sounds,” Mrs McGowan explains. “If Aiden is stuck with a word, he sounds it out - as he just did with `through’. If he’s still having trouble, he looks at the picture. At first, if he didn’t recognise a word, he would just leave it out. Now he works at it. He is coming on in leaps and bounds.”

Children who struggle to read need to be taught techniques to engage with a text, rather than skimming its surface, Mrs McCandlish says. “It’s working well. They accept challenges now. They use word attack strategies where once, if it seemed hard, they would just say `I can’t do that’.”

Young Tammy is tackling a game that does look hard - matching words such as “which” and “witch” and “whether” and “weather” to the right pictures.

“I find it easy now,” she says. “Like I know the picture of a witch goes with the word `witch’, because I look for the `i’ and the `t’. There were a lot of words in books I didn’t recognise before. But I’m starting to get good at reading now.”

“Chunking” a word - looking and sounding its parts - is one technique that has worked well with Tammy, student teacher Suzanne McGonigle says. “We also let her read books that she enjoys and we read some of them to her. A lot of children don’t get read to at home.”

That is part of the problem, Mrs McCandlish says. “If they’re exposed to very limited texts, they don’t have a picture of themselves as readers. On the other hand, if a child is struggling with reading, it is hard for parents to get him interested in books at home.

“The feedback on this scheme from the parents has been phenomenal. They’re telling us their children are now reading and doing their homework, and their attitude to books has changed completely.”

Forty-four student teachers for 10 children sounds hard to organise, especially when it has to be done by students in their spare time. Good communications are the key, say three student teachers who - with a colleague - are tutoring one Balornock pupil.

“We have folders where we write quite extensive notes to each other, about what we’ve been doing, what we’ve learned, what works and doesn’t work,” Amanda Oates says. “We also meet up at university and discuss it.”

An early discovery was that one young boy preferred talking to reading, Alison Montgomery says. “He would start as soon as you brought out a book, as if he was trying to distract you. But we ended up learning a lot by stopping and listening to him, and not trying to make him read right away. That’s how we found out he liked drawing - which we then used to motivate his word-recognition.”

There is a balance to be struck when trying to get a pupil to do something that’s given him few past successes, Laura McLean says. “You want him to read because it will benefit him, but you don’t want to force him and put him off even more. The first week it took a lot of coaxing from his teacher to get him to come and work with me. Now he’s up and out of his seat right away.”

A vital lesson to take back to whole-class teaching is to look below the surface, Miss Oates says. “One boy can come across as confident. He’s good at putting up a front. So if he was in your class, you might not realise his difficulty. It won’t be easy, but I think you need to work one-to-one with a class, as much as possible, to find out where they are.”

Miss Montgomery agrees and believes it can be done: “You have to get to know every child in your class, what makes them tick, what they like and don’t like. I think a good teacher can do that. When children know you care about them, they want to work for you.”

The outcome of all this literacy support from University of Strathclyde students is that the self-esteem of 10 formerly struggling children at Balornock Primary has been permanently improved, Mrs McCandlish reveals. “They used to see themselves as poor readers. So they avoided reading. Now they think of themselves as readers.

“When you get children hooked on reading - and they see it as something they can do and enjoy doing - that’s when they are ready to learn.”

- Reading at 16 linked to better job prospects: bit.lyglMhuF

- Strathclyde Literacy Clinic: bit.lyYfDoIz.

`IT GIVES THEM ANOTHER WAY OF LOOKING AT TEACHING’

Jane Thomson, University of Strathclyde lecturer

“So far only third- and fourth-year BEd students have been working on the literacy project at Balornock Primary. But we’d like to get second-years involved too. It gives them another way of looking at teaching and learning. It develops their philosophy of what’s important in a classroom.

“Observing a child and responding to individual needs helps students enormously. They learn they have to make time for the individual interactions that show them who is struggling with reading and writing.

“Our plan now is to include this type of literacy project in one of the course modules, so that the students are not giving up their own time - which is difficult for them, especially in fourth year. We are currently talking to Glasgow City about taking the clinic out into more schools. It would be great to get funding to allow us to do that. We are making a real difference to disadvantaged children.”

Sam Harte, class teacher

“It is incredible how rapidly my students have advanced with the help of the reading tuition from the University of Strathclyde. It’s made a huge difference to what they are capable of doing. It has had a big impact on their wider learning. Their attitude has changed completely. Reading used to be a chore for them. Now they enjoy it.”

Photo credit: David Gordon

- Strathclyde Literacy Clinic: bit.lyYfDoIz.

Keep reading for just £1 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £1 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters