Picture a piece of common ground. This common ground is used by four villagers who each keep a cow on it. They milk their cow to meet their own demand and sell any surplus in the village to buy luxuries they might want.

One day, a villager realises that if he bought a second cow he would have far more milk to sell and so would be able to buy more for himself and his family. The other villagers see this and so also buy an extra cow to graze on the common land. All this milk on the market causes the price to fall and suddenly our first villager needs to now add a third cow to get the extra money he wanted. The others feel compelled to do the same. Over time, more and more cows get added until the land is destroyed and can support none.

This is the economic theory termed “the tragedy of the commons” by the economist William Forster Lloyd - and further developed by the ecologist Garrett Hardin - to describe how any shared resource will be exploited by those that share it in their own self-interest, rather managing it for the common good - and will inevitably be destroyed. I think we can see the tragedy of the commons being played out in how GCSE interventions are used in schools to secure the shared resource of pupil grades.

Workload is soaring

The term “intervention” was originally used to describe a programme of support given to specific children who required it. When I was at school and taking my GCSEs in the late 1990s, the only additional support available were a few revision classes just before the final exam.

How things have changed. Now intervention means people employed to work with pupils one-to-one, revision classes going on throughout the Easter and half-term holidays, residential revision camps and “period 6” sessions after school running all year, in which teachers are expected to teach an additional lesson to Year 11 without it being taken into account on their timetable. Workload is soaring and pupils are either exhausted or expecting to be provided with a constant safety net of additional classes if they weren’t paying attention the first time. And all to what end?

Essentially, the term “intervention” as it is used now isn’t about carefully planned intervention at all. What it really means is “additional curriculum time” and the pressure on teachers and schools to provide it is huge.

An intervention arms race

This takes us back to the tragedy of the commons. We are all competing for the same resource, for the grades that pupils get in their exam. If you dramatically increase the amount of teaching time a subject receives, it’s not surprising if results for that subject go up. If one school boosts their results by running additional lessons for all their Year 11s after school, then the rest of us have to do the same to keep up. If one school boosts results by cancelling the Easter holidays and running intensive sessions then we must all do the same or worry that we will fall behind. We have created an intervention arms race.

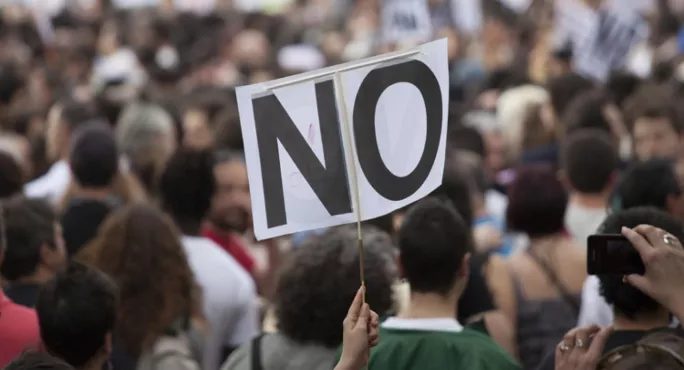

The only solution seems to be some sort of unilateral decommissioning. We all need to start saying “no”. Excellent lessons for five hours a day, five days a week for 40 weeks of the year should be enough time to teach what needs to be taught. There are many wonderful schools who are already taking this step and saying “no” to revision sessions in the holidays and endless additional lessons after the school day. In these schools, intervention has gone back to meaning carefully-targeted support where it is most needed, usually delivered through high-quality teaching, and time after school can be reclaimed for extra-curricular activities or independent study.

The tragedy of intervention is that by engaging in this arms race we are just making teaching less sustainable. It is time to stop and address the damage that has been done before it is too late.

Mark Enser is head of geography at Heathfield Community College in East Sussex and blogs at teachreal.wordpress.com

Want to keep up with the latest education news and opinion? Follow Tes on Twitter and Instagram, and like Tes on Facebook