It is hard not to feel a little gloomy as the nights get longer and the weather colder.

And many of us are inclined to feel more than a little gloomy without those triggers.

The 2013 UK chief medical officer’s report indicated that poor mental health was the largest single cause of disability and the leading cause of sickness absence.

Quick read: Wellbeing: Mental health is a family affair

Quick listen: ‘We have no idea if most things in education work’

Want to know more? True grit? Maybe teaching zest is best

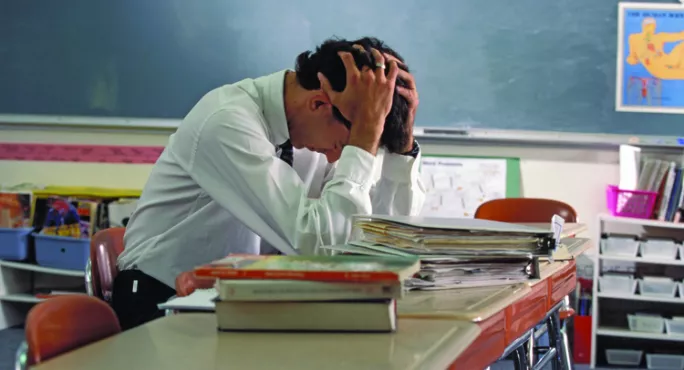

Education is one of the occupations with the highest rates of mental health-related absenteeism and presenteeism, while poor mental health is one of the most common reasons given by teachers who take early retirement.

The numbers involved are truly shocking; more than a third of teachers in a Scottish study, nearly half in a similar study conducted in the Irish Republic.

The burnout cascade has been beautifully described by academics Tish Jennings and Mark Greenberg.

Teachers’ mental health

Professional pride, vocation and stigma may prevent teachers from taking time off or seeking help; stressed, burnt-out or distressed teachers are less effective at teaching and more likely to have poor teacher-pupil relationships, which may lead to poorer mental health and disruptive behaviour among pupils.

The increasingly exhausted and burnt-out teacher is more reactive and irritable with their class, who in turn become more unsettled and less engaged, leading to increased stress, distress and burn-out for the teacher.

Notwithstanding the human cost to teachers and their families, teachers who retire early take their knowledge and experience with them.

The pressure on those left behind may be intensified not only by the gap in the workforce but by the loss of experienced mentors.

Boosting teacher wellbeing

So how should we respond to look after our teachers who are a precious resource?

The good news for those currently struggling with poor mental health is that anxiety and depression are tractable. We have effective treatments and they are more accessible than they used to be.

The development of mental health conditions is not due to a lack of moral fibre or weakness but results from a complex interplay of an individual’s genetic inheritance, their social and psychological resources and the curve balls that life may throw at them.

It is hard to make these conditions worse by talking about them, and a sincere enquiry and good listening ear is often the important first step to seeking help and recovery. If you are worried about a colleague, gently ask if all is OK with them.

The government’s five-a-day for mental health recommends connecting with others, being active, taking notice of the world around you, keeping learning and giving of yourself to others.

Teachers certainly do not lack with number five, but may struggle to look after themselves. Which is where these simple conversations about wellbeing can be invaluable.

We all need to look after ourselves, as well as each other.

Tamsin Ford is a professor of child and adolescent psychiatry at the University of Cambridge