Trojan Horse: What England can learn from the growing pains of integrated schooling in Northern Ireland

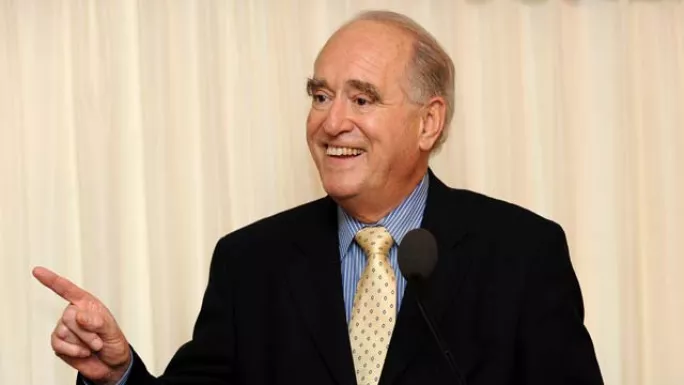

Lord Mawhinney, former Conservative party cabinet minister, writes:

As the role of schools in promoting respect for religious and cultural difference is under the microscope in England, it is timely to draw lessons from the work of Northern Ireland’s integrated education sector in overcoming division.

Since the 1920s, Northern Ireland schools have been designated either as state or Catholic schools. When I became Northern Ireland’s education minister in 1986, 97 per cent of Catholic children went to Catholic schools as a matter of parental choice. By definition, therefore, state schools overwhelmingly catered for Protestant children. There was no legal discrimination - in either direction. So, like me, Northern Ireland’s young people grew up having little or no contact with religiously and/or culturally different peers. It was a system that, while not directly responsible for the outbreak of The Troubles in 1969, nonetheless helped to polarise the community along religious and cultural lines.

One of the most memorable moments of my political career was putting integrated education in Northern Ireland on the statute book, in 1989. I knew it had to be done to support the strong desire of many parents for their children to be educated together in a school that equally valued both traditions in my native Ulster. And I understood that this was a task that had to be led by me, as the minister. There was little support among local MPs, the leaders of the main churches or the education establishment.

This determination resulted in the 1989 Education Reform Order, which placed a statutory duty on the Department of Education to encourage and facilitate integrated education. I put those words in deliberately because, without them, I was not confident that the department would throw its weight behind facilitating those parents who wanted integrated education for their children. It was intended to ensure that parents could either start schools from scratch, with government support, or that parents could vote to transform an existing school to integrated status.

The result of that legislation has helped pave the way for the 62 formally integrated schools, educating 22,000 children that we have today.

Integrated schools do not airbrush difference out of the picture. They work to explore and celebrate diversity, encourage self-expression and promote respect for others’ traditions and beliefs. There is nothing either to fear or to cause concern in these ideals. Yet this model represents only 7 per cent of the total school population in Northern Ireland. Why, 25 years on, have we not seen a steady surge in integrated school places?

The parental desire for integrated education is certainly as strong now as in the darkest days of the conflict. However, despite the recognition of the existing statutory duty in the 1998 Good Friday Agreement, I, and others, have been frustrated by the devolved Northern Ireland Assembly’s lack of support for integrated schooling.

Radical reform in education planning requires bold leadership and a willingness to take risks in the name of “doing the right thing”. And radical reform is certainly still necessary.

Perhaps politicians fear that shared schooldays will ultimately threaten tribal politics; as if denying what we hold in common has ever benefited Northern Ireland. Perhaps they fear the wrath of different religious institutions keen to preserve their vested interests and grip on education.

Whatever the reason, the growth of integrated schools has been stifled. In its place, they have opted for more sharing of school facilities and increased collaboration between different schools. This, in itself, is a good thing. But is this as good as it gets? If this is a step in the right direction, how do we plan to reach the end of the journey?

In a landmark court case, Drumragh Integrated College in Omagh resorted to the High Court in Belfast to seek a judicial review over a Department of Education refusal, last year, to allow the school’s expansion. Omagh has experienced great pain, not least through the single biggest atrocity in the Northern Ireland conflict. Of all places, integrated education could be said to be needed here and local parents say they want it.

The successful judicial review exposed two major failings in the Department of Education in Northern Ireland. One was its failure to understand the very meaning of the actual statutory duty placed on it. Secondly, it failed to take this duty sufficiently into account when planning education. This must change - and fast.

The department is currently rationalising the schools estate. It has, so far, chosen to plan the future of education based not on expressed demand, but on the existing cohort of schools in an area. It runs the risk of creating the impression that it is more worried about upsetting local political/educational establishments than doing the best it can for children’s formative learning. The High Court judge in Belfast acknowledged that this flawed planning process assumes no growth in integrated schools, essentially ignoring any wish for change from local communities.

The 1989 Education Order created a rare opportunity to address the fragmentation of our education system in Northern Ireland. We should be trying to create a situation where all schools belong to everyone - the wider community as well as the pupils - promoting a sense of ownership and loyalty without the mutually suspicious rivalry which currently prevails. We should act quickly to build a truly shared and integrated system of schooling - something Northern Ireland could proudly show to the rest of the world.

Related links

Trojan Horse: Report finds ‘clear evidence’ of ‘extremist views’

‘Ofsted must learn the lessons from the “Trojan Horse” saga’

Keep reading for just £1 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £1 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters