- Home

- When exclusive is inclusive

When exclusive is inclusive

This article has been put in front of the paywall as Tes believes it is an important issue to highlight to as many people as possible. The education outcomes for children in care are notoriously poor compared with their peers and solutions that appear to improve the chances of these young people need to be highlighted so that they can be better researched and discussed.

“It’s quite a rush when you first go into care. Let’s get them a bed, let’s get them food, let’s get them therapy. You take it day by day because that is what you do when trauma occurs. People stop thinking about the future. I stopped thinking more than a month in advance. But before you know it, life has caught up to you. You think, ‘What is happening?’ No one has made any plans. Education gets left behind.”

Alice* is 15 years old. She has been in and out of care from a very young age. And she has one aim: to give vulnerable young people at risk of becoming “looked after” the same chance of “equalising their opportunity” that she has had since the age of 11.

That chance? A place at a boarding school. And there are some very influential people - including some within the Department for Education - calling for the very same thing.

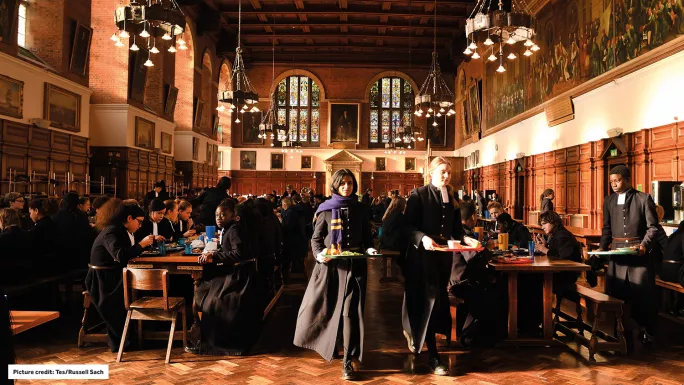

At Christ’s Hospital school, the streaks of low winter sun splinter off the spinning baton of the teenage bandmaster and disappear into the thick black cloth of his Tudor uniform, the pupils at Christ’s Hospital march across the quad in rows of four: perfectly aligned, all as one, all seemingly the same.

But these students are not all the same - not economically and not in terms of the lives they leave at home to come and board here. This £33,000-a-year independent school, with its 450-year-old traditions, has one of the most diverse student bodies in the country.

“We are a truly comprehensive school - more so than, you could argue, many state schools are,” says headteacher John Franklin (pictured below). Fourteen per cent of our pupils pay no fees at all and 40 per cent pay less than 10 per cent of fees; 19 per cent pay full boarding fees and 7 per cent pay full day fees. According to the Independent Schools Council’s 2017 Census, across its schools (which include day schools) 1 per cent of students pay no fees.

The school, which is situated in Horsham, West Sussex, actively seeks out children with what Franklin describes as a “boarding need”. It has done so since the school was established by King Edward VI in 1552 as a charitable school to provide “a little learning for fatherless children and other poor men’s children”.

A substantial endowment has meant that Christ’s Hospital has never strayed from its mission: the proportion of fee-paying students is less a financial necessity and more a social one, says Franklin. “If you don’t get the mix right - if you have a school where no one pays fees at all - you’re not achieving the aim of creating a different situation for these children,” he says.

The school is unashamedly selective academically. But the tests, says Franklin, assess potential, not attainment. For proof of that, he points to the make-up of the student body.

Many of the young people were full-time carers for parents, come from abusive homes or have parents with severe mental health issues. Poverty is a common factor. They’re here without tutoring for the test and in spite of the fact that their school life has been severely disrupted.

Less than 20 miles away, King Edward’s school in Witley has a similar student population. It was set up at the same time as Christ’s Hospital, for the same purpose, and the two remain connected.

Headteacher John Attwater says that around 25 per cent of pupils (around 100 individuals) have a boarding need. “Of the 100, the large majority are supported to over 80 per cent of the fee, and several to 100 per cent or more,” he explains.

These two schools are not alone in offering places to children with a need to board. The model is called assisted boarding. Schools offer bursaries to children with a boarding need and local authorities and/or charities pick up the rest of the tab.

In general, a child is considered to have a boarding need if their capacity for normal happy development is compromised by seriously adverse circumstances at home.

These situations can arise through mental or physical illness, abuse, bullying, extreme poverty or the parent(s) simply struggling to cope. Some of the would-be beneficiaries are child carers. All pupils will be at risk of needing to be taken into LA care.

Students return to their families during holidays, or if that is not an option foster or alternative care is arranged.

The number of assisted boarding places that Christ’s Hospital and King Edward’s offer far surpasses that offered by other boarding schools. Wymondham College, a state boarding school in Norfolk, has about 30 such children and the state boarding sector tends to take more than most.

Then there is a small group of independent boarding schools that take around 10-15 students across the year groups; a few more have just one or two of these students in the school. Too many, it could be argued, take none at all.

“Someone at the school just said ‘This kid is different’ and thought about Christ’s Hospital. I was lucky. The family…well, there wasn’t a family, so the care workers thought, ‘Well fine, give her a shot’.”

Alice found her way to Christ’s Hospital thanks to a referral from a primary headteacher, but the vast majority of young people in her situation - those who are in care or at risk of becoming looked after - are offered assisted places at boarding schools through charities such as SpringBoard and The Royal National Children’s Foundation (the two announced a merger in May) and Buttle UK. Charities part-fund and/or facilitate around 700-1,000 places per year.

Children come to the charities’ attention via referrals from a variety of sources: children’s services and social workers, primary schools and youth organisations, and families themselves. Some LAs also place children in boarding schools but the numbers are much lower than through charities. Not every child with a boarding need will benefit, say the charities and LAs: they seek out those they feel will seize the opportunity and those who they think can cope with the boarding environment.

Once a child is identified, the family, the young person, the organisations involved with the family and the chosen school (families can approach a school, or LAs and charities can link with schools) all have to agree that it is the best option. One LA social worker says that roughly 1 in 5 of the children approached to board end up boarding.

Franklin says he doesn’t like saying no but sometimes he has to. “We encounter some children who have difficulties that are just so profound we are not able to provide the support they need,” he explains. He says an example would be a child who is a danger to themselves or others and so needs care closer to 1:1.

“Boarding school got me together: I found out who I was. I now have the solid foundation that should have been provided by someone else, but wasn’t. When you come into care, you’re quite an isolated unit - that’s how you keep yourself safe. So the network that a boarding school gives you is so important.”

Alice has been a full-time boarder for four years at Christ’s Hospital. She says the main benefit has been the stability it has offered.

Jasmine*, on an assisted place in the lower sixth at a large boarding school in the south, agrees. “Day school - yeah, you can focus on being there but you still have to go home. You still have to wake up at home. You have to deal with everything before and after school. That means you don’t do as well - it means you don’t focus as well. Because it is always there, in the background.”

Norfolk County Council (NCC) is, according to many, far ahead of other LAs on assisted boarding (it currently facilitates around 18 assisted places). Judi Garrett, from NCC Children’s Services, says that boarding provides numerous benefits and is more cost-effective (she says that putting a child in care will cost £50,000 per year on average).

“They do not have to worry about basic-level needs - warmth, food - that we take for granted,” she explains. “We are also creating a better outcome for the child as (where it is safe) they are able to stay with the family unit but for less time.

“And they have a lot more belief in themselves when they attend a boarding school. Before, they have almost given up, that this is going be their lot, but they go to these schools and they feel that they can achieve more as the situation is so different and they are enveloped into a very aspirational culture.”

That leads to improved attainment, says Buttle UK chief executive Gerri McAndrew. She says that 15 per cent of children in care achieve 5 A*-C GCSEs, including maths and English (a government report in 2015 put the figure at 14 per cent), while 61 per cent of those children supported by Buttle in 2016 achieved that aim.

SpringBoard commissioned the National Foundation for Educational Research (NFER) to conduct a five-year formal evaluation of its work (2013-18) and, so far, it has also found academic benefits.

In addition, it has found that students benefited from broadened horizons, enhanced future prospects; improved social skills; increased awareness of social diversity; and increased confidence and wellbeing.

It also pointed out key benefits for the schools and the other students at those schools, including improving skill sets of boarding staff and broadening awareness of social issues among wealthier students.

This is something that Attwater is keen to stress: “Our students benefit hugely from being aware of some of the difficulties that face many people in our society, which increases their compassion, empathy and instinct to serve others.”

“It can’t be patronising. It can’t be, ‘You are in need, we’re going to save you.’ It has to be about a partnership. It’s not about being the hero.”

Alice knows of cases at other schools where boarding for children in need has not worked. And Franklin concedes that Christ’s Hospital loses one or two students per year, usually due to behaviour issues or the child being unable to adapt.

“The problems arise when the damage that has been done before is so ingrained and severe that they cannot adjust,” he says.

Christ’s Hospital and King Edward’s have extensive pastoral services, a comprehensive medical team and very close links with child and adolescent mental health services (Camhs), to try to help students. For the most part, the challenges are overcome.

Off the record, headteachers and LAs say that where the assisted boarding model fails, schools are simply not set up as well on the pastoral side to support these young people. But Douglas Robb, headteacher at Gresham’s School in Norfolk - which has around 10 in-need children on its roll at any time - says this is a poor excuse.

“The home lives and situations of students who pay full fees can actually be even more complex [than those of assisted boarders],” he argues. “The emotional difficulties the children can suffer through neglect or issues at home are just as severe, if not more so. Wealth does not enable you to buy your way out of such problems.”

He says problems are actually often due to a school not fully buying into the model. “I know of a student at another school who was an assisted boarder who did not continue in boarding,” he says. “I think the general culture in that school was not conducive to that child being able to assimilate.”

This is a common complaint among assisted-boarding pupils in schools where they may be in the extreme minority.

“There was a massive difference between me and friends in the technology they could buy or the additional academic tutors they could afford,” explains one former pupil, who is now at university. “I know [the experience] makes lots of ‘disadvantaged’ kids feel all the more disadvantaged when, in reality, they are just not excessively privileged.

“I remember crying when I saw a friend’s house for the first time - when put in perspective of perfect families in mansions, your life can seem all the worse - the idea that a fish doesn’t know the water it’s swimming in is salty.”

And he is sympathetic to the criticisms many have of assisted boarding places: that they educate a young person away from their family, community and identity.

“Rather than it being some sort of cultural exchange, it is very much the school that is dictating the relationship,” he explains. “I feel these conditionalities undermine the altruism of transforming lives. And I have seen lots of friends go home thinking they’re above their home. And I have seen so many children thrown out of school because they were too disruptive and struggled to adapt to what was an alien environment.”

Attwater is keenly aware of the issue. “I think this is a danger of which we are all aware, but it has not been our experience,” he says. “Many parents who are struggling are desperate for their children to be in a better environment - [they] actively want this. It can actually be a rallying call in that community to help the individual and their success can instil a sense of opportunity and ambition for others.

“[But] key to this is that the education is understood to be a partnership between the family (and/or social worker) and the school, not something that we take students away to do instead of the family.”

“Unique? I don’t think I am. It is painful how many young people don’t have this opportunity.”

Alice insists that she is one of the lucky ones out of thousands of children who should get a boarding opportunity but don’t. Indeed, everyone involved in assisted boarding believes only a fraction of the number of students that could benefit from boarding have places.

So why hasn’t assisted boarding scaled up? A big part of the problem is capacity. There are only 39 state boarding schools in the UK and only 480 boarding schools in total, and there is limited capacity to offer reduced fees in the vast majority of those schools owing to cost pressures.

Robin Fletcher, chief executive of the Boarding Schools’ Association (BSA), says the schools are doing the best they can.

“Where facilities and support match the child’s need, boarding schools are willing to help,” he says.

SpringBoard says that in its four years, it has placed students in 70 schools, with 100 schools expressing an interest.

Obviously, if LAs were willing to pay the full fees, or charities were, the business case would be less of an issue. But Robb says that while anyone not wanting to do this would be “a fool”, there may be instances where schools are not as active as they could be.

“There has been reluctance to engage with state agencies from some boarding schools,” he says. “Perhaps it is a lack of confidence.”

Yet even if there was more capacity, would LAs be willing to fill it?

Large-scale assisted boarding used to be the norm. Before the 1980s, local authorities used to support more than 10,000 assisted places. A shift in approach to focus more on foster care and keeping children with families - and away from “institutions” - saw those places disappear. The BSA says that, at the time of writing, just 26 LAs are currently funding 60 placements and a further six are considering placements

“Boarding ceased to be on the radar of LAs and so it is not thought of when intervention is considered and nobody in the relevant authority has experience of it,” says Attwater.

He says that lack of knowledge is not the only issue: “There has been pressure on LAs in funding terms for interventions to show quick results and impact, whereas this is a long-term intervention, particularly as the admissions cycle for many schools can be months long. And it works best as a preventative measure but too many LAs are just firefighting.”

He concedes that another factor may be a lingering prejudice against the idea of boarding, “generally not at the top of LAs but lingering within the middle strata”.

Fletcher says LAs do have a statutory duty to consider boarding school placements when placing looked-after children and concedes that “outdated views” may play a part in limiting take-up of that option.

But he thinks a lack of knowledge about assisted boarding is the major factor, which is why the BSA is supporting a new initiative, sponsored by the DfE and backed by education minister Lord Nash, called the Boarding Schools Partnership. To be launched in July, it will be “a way of giving LAs the expertise and resources [for assisted boarding] when they need it,” says chair Colin Morrison. He stresses that authorities have been overwhelmingly keen to be involved.

Will that interest convert to more LA-led placements? Not without more boarding capacity, according to some, and others claim that the whole model should be limited until there is better evidence that assisted boarding actually works.

While there have been a number of studies that have looked at assisted boarding, and numerous successful case studies, there is an argument that there is no single piece of research to prove beyond doubt that this should be an option. The Education Endowment Foundation (EEF) and Buttle had planned the largest study to date of assisted boarding to fill that gap, but it fell through earlier this year.

“On a purely theoretical, hypothetical basis, you can see why it might work,” says Sir Kevan Collins, chief executive of the EEF. “It creates a disruption to the pathway to care, it takes a child out of an environment, perhaps out of a peer group, too, that is causing concern, and it gives respite to all involved.”

He describes current outcomes for children in care as “extremely poor” and says other possibilities therefore need to be assessed.

“[So] I am angry that, with funding in place and the process all agreed, we could not find enough LAs willing to work with us. I don’t know whether that is down to prejudice or something else,” he says.

Morrison believes it was “something else” - mainly that LAs may have been wary of choosing “specific new placements primarily for research purposes”. He says the thirst among LAs to see if the option works is definitely there. “No fewer than 110 of the 150 children’s services in England have, for example, registered with us,” he says.

Off the record, though, across education and children’s services, you do hear comments about boarding school being “not right for these kids” and “why would a private school do any better for a child than a state school”. The scale of prejudice is debatable but that it exists in some capacity is undeniable.

Would a large-scale, high-profile study have changed some of those opinions and boosted referrals while giving LAs the ammunition to push through more assisted places? Perhaps. But perhaps the BSP will make the difference (it plans to conduct a study on the scale of the one the EEF was planning); perhaps authorities will slowly come on board regardless; perhaps the shift will happen organically.

But it is just as likely this will remain a niche option and some believe it should remain so.

For the charities, schools and young people already involved in assisted boarding, though, that would mean a large number of our most at-risk children would be failed by the system.

And Alice is determined to force a change so that does not happen.

“My work to widen awareness is a thank you,” she says. “This has changed so much for me. I am prepared for my future - if I was not here, I don’t think I would have been. That future is vastly different to what I would have otherwise.

“I have had someone say I can do something else other than just be a survivor. That I can ‘thrive’ - and that is not a word that is often used when you are in foster care.”

Jon Severs is commissioning editor of Tes. He tweets @jon_severs

*Names have been changed to protect students’ identities

Keep reading for just £1 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £1 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters