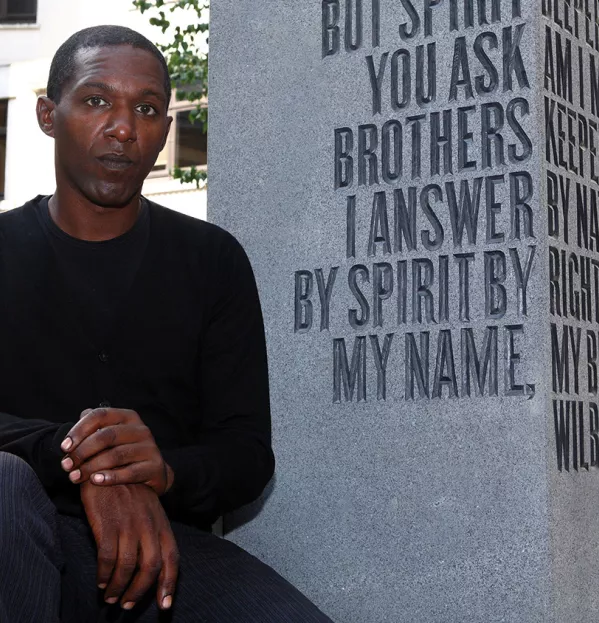

10 questions with... Lemn Sissay

Lemn Sissay MBE is a poet, playwright and author who published his first book of poetry aged just 21. He was appointed the official poet of the London Olympics in 2012 and was made chancellor of the University of Manchester in 2015.

He has written numerous novels, plays and works of poetry, winning several awards along the way, including the 2019 PEN Pinter award.

Sissay spent much of his childhood in a care home, which, he says, made his relationship with school even more profound. He talks to Tes about his most memorable teachers, school trips, extracurricular activities and just how important education was and is to him still.

You can listen to the full interview on the My Best Teacher podcast or read an abridged version below.

1. Where did you go to school?

I went to Leigh CofE, a comprehensive in the Lancashire town of Leigh. Next to the school, there was a farm called Marshes Farm. We would walk from the children’s home along Old Hall Mill Lane - which was a gravelly, pot-holed lane - and we would see the horses by the farm and dodge the massive puddles in that country road that would lead us to school. It was very misty in winter and full of blossom in summer. It was a bit Cider with Rosie.

2. Who was your favourite teacher?

His name is Mr Unsworth. He was bald, he drank bitter - not at school - and he was a rugby-playing union man, straight out of central casting for Kes. He had a broad Lancashire accent and a belief in his students.

3. Why did he make such an impression on you?

He would look at my poems, and not necessarily the poems that I was writing for class or reading for classes - he looked at the poems that I was writing at home.

He gave me feedback and being seen in that way was inspiring to me. It meant that what I did mattered. What I loved was that he gave me critique, so he wouldn’t just say, “Oh, that’s brilliant” - he would say, “That’s a bit repetitive and that image is OK but you’ve got better in you”.

I was really excited that somebody cared enough to be able to be compassionately critical of what it was that I loved.

4. Was that a key moment for you?

If a child ever approaches a teacher with work that they’ve done at home outside of the school curriculum, a teacher should always give attention to that.

I took my poems to my teacher to say that I’d written them and I think it would be very easy for teachers to say, “OK, but just make sure you deliver your homework”.

But, actually, if a child ever says, “Oh, I’ve drawn this” or “I’ve written this”, and it is not part of the curriculum, a teacher should always be beholden to follow that lead.

5. Have you kept in touch with Mr Unsworth?

I interviewed him for an Imagine documentary on the BBC recently and I invited him to the ceremony when I became chancellor at the University of Manchester.

When I interviewed him for the documentary, he told me that when he saw my work, it had an effect on him and he remembers the moment of reading it and thinking, “Wow, how did he do this?”

I also invited him to an event that I was doing at the Royal Exchange in Manchester when I was in my twenties and either he told me, or somebody who saw him told me, that he wept during my performance.

I’ve invited him to a few events and I’d say we were sort of like distant friends now. His name’s Ian, but I can’t call him that. I still call him Mr Unsworth.

6. Do you think that connection with former students is important for teachers?

Teachers don’t get the feedback that they deserve but the more there is for teachers about the good work that they do, the better they feel.

I guess you can’t institutionalise it - students will find their way back to teachers in their adult lives in their own way.

Being stopped on the street and being told, “I remember what you did and it really made a difference in my life”… It’s a good thing to do. It’s a way of giving service, a way of giving back, and I did that.

I went back to Mr Unsworth and I woke his memory of me. I knew that he knew about me, about the things that I’ve done in my life, but it was just a good thing to do to walk back and say that what [he] did 20 years ago has had an effect on what I am now. And he can look at my work and see that my work affects other people, and that he’s part of that.

7. What was the standout subject or activity at school for you?

I really, really loved drama. The beauty of drama was improvisation, and trying to find ideas where there were none before and make them come alive.

And also football. I wasn’t a great footballer but I loved playing football. And I loved being on the football team. And I got some studded boots and I used to play on the right wing or right midfield, and memories of very cold, wintry, hard soil …Yeah, that was lovely.

8. You grew up in a care home. How important was school to you during that time?

A lot of people say (it’s become a cliché), “Oh, my children spend more time with the teacher than they do with me at home”. But for a child who’s in a children’s home, that’s actually quite profound. The almost parental energy, which is lacking in the children’s home, is reflected in teaching.

That’s a big thing to say, a big responsibility for schools to have for a child who is in care. And I absolutely loved school, absolutely loved it - because I could smell family on all the other young people.

9. No doubt this made the teachers even more important, too?

I think [because] there was no family at home, I was quite demanding of the teachers. A teacher who inspired me was as close as I could get, essentially, to the parent. Also, a teacher who admonished me was as close as I could get to the parent.

That’s why I think that how we treat young people in caring schools is a real test of our teaching skills. Teachers are not parents, they are teachers, [but] whether a child reflects on to the teacher the responsibility of a kind of parenthood is another matter.

But teaching is part of what it is to be a human being, from the moment a child is born, so I don’t see teaching as just a matter of school - I see it as being a central part of what it is to be human.

10. Do you think that depth of skill in teachers is understood?

The effect of the teacher on everybody is really profound. In meditation, people talk about gurus and, in many ways, the teacher is part of that tradition of a teacher being not just a talker but also a listener.

They can see which child has not slept properly the night before, which child is so consumed with worries at home that they cannot properly get their head round it [a lesson], which child smells because they’re not being washed properly by the parents. All of these skills are being employed besides delivering the lesson plan. I think teachers are very giving; they give a lot away.

Lemn Sissay’s memoir, My Name is Why, is out now, published by Canongate. He was speaking to Dan Worth, senior editor at Tes. You can listen to the full interview on Tes’ My Best Teacher podcast

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters