7 easy steps to curriculum planning

There is nothing I love more than curriculum planning. Looking at the programmes of study - and deciding what should be taught and when - is the process by which everything in a department lives and dies.

However, the amount of thought that goes into these long-term plans will vary enormously from school to school.

I have worked in departments where the plan for key stage 3 grew organically over the decades as people thought of interesting topics they’d like to include, and where the plan for GCSEs was to simply start at the beginning of the exam specification and work through it, hoping not to run out of time.

I’d suggest that a more structured approach is useful. The following steps will help you get the best from your curriculum.

1. What would you love to teach?

The first step in creating your curriculum is to sit down as a department and discuss what you would love to teach. Questions to prompt the discussion might include: what is the very best aspect of your subject? What should every child know before leaving your care? What part of your domain really matters the most? Make a wishlist of what you would include for every key stage you cover.

2. What do you have to teach?

Now for the reality check. What do you actually need to teach? If yours is not an academy or free school, the teaching requirements will include the national curriculum for KS1 to KS3, then GCSE and A-level exam specifications.

3. Make a match

Put your two lists side by side and play “spot the similarities”. You might find that many of the things you would love to teach are already national curriculum topics.

Otherwise, you will need to get creative, working out where the elements you want to teach can usefully fit.

There is a wealth of advice available from subject associations on how different topics can be aligned to the curriculum.

4. Remember what came before

To plan your programme, you need to have a good knowledge of what your pupils already know and can do. You want to build on and revisit past content without teaching it all over again. You can usually find out what previous key stages have covered, but it is more difficult to find out what the pupils have actually learnt. This is where teacher assessment and conversations with your team come in. Look at the data and ask colleagues what pupils already know well and what they have misconceptions about.

5. Consider depth and breadth

The next step is to work out in how much depth you are going to cover each area. This is one of the trickiest aspects of curriculum planning, as there is little guidance about it either in the national curriculum or in many exam specifications.

For example, the KS3 geography curriculum specifies that we teach key processes in “rocks, weathering and soils”. In theory, we could spend weeks studying these or cover the lot in a single lesson. This is where you must use your professional judgement. Is this an area you feel passionately about? Does it form a core component of your subject? How much knowledge of this topic do pupils need to access what comes after?

6. Identify ‘threshold concepts’

There are certain ideas in every subject (termed “threshold concepts” by Jan Meyer and Ray Land) that pupils must grasp in order to move forward.

In geography, for example, if pupils have not fully understood the threshold concept of erosion and weathering, they won’t be able to understand the formation of landforms and their management. Identifying these threshold concepts for your subject will make curriculum planning more effective as you will know where to target your attention and how to start ordering your topics.

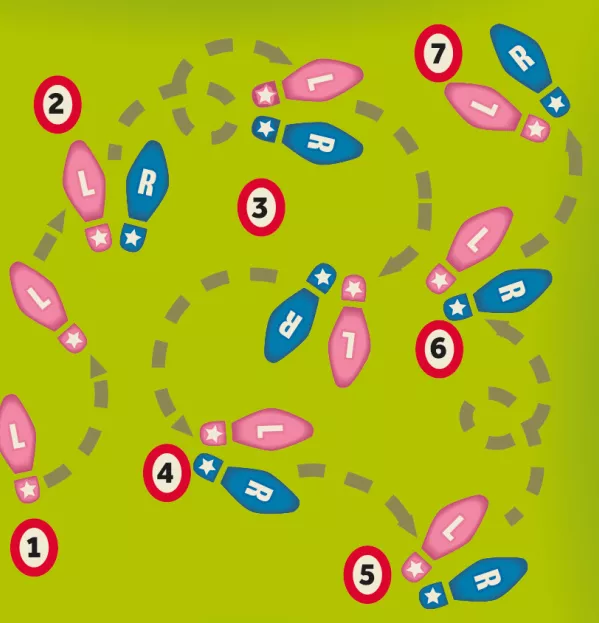

7. Create order from chaos

By now, you should have a list of what you need to cover and a good understanding of why you need to cover it. The final step is to put your ideas into some sort of order. One debate raging in my subject at the moment is whether to teach units thematically (weather and climate, migration, river landscapes) or regionally, through place studies (East Africa, Haiti, Russia). There are similar debates in history about whether to teach a chronological programme of study or units organised by theme.

How to order your topics is ultimately a personal decision for you to make as a head of department or subject lead. One approach that has worked for us is to combine the two methods: our Year 7 pupils focus on building the base knowledge through a thematic approach and this knowledge is then applied to regional studies in Year 8. This builds in opportunities to revisit previous topics and has helped us to start creating a spiral curriculum (where pupils revisit topics throughout their school career to reinforce learning and expand understanding) with clear progression.

Progression, of course, is what sits at the heart of successful curriculum design. It shouldn’t be a case of just one thing after another; there should be a sense that each topic connects to what has come before and that we are all heading somewhere specific. The responsibility for planning this learning journey is what makes being a head of department such a privilege.

Mark Enser is head of geography at Heathfield Community College in East Sussex

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters