Apprenticeships: why new starters are so important

The Department for Education’s latest apprenticeship figures, covering August to October 2020, paint a worrying, if not unsurprising, picture. In nearly every category, the number of people starting an apprenticeship in the first quarter of the 2020-21 academic year was down on the number doing so in 2019-20. Perhaps we shouldn’t be too surprised: despite lockdown easing over these months, large portions of the economy were operating under government restrictions and many businesses will have struggled to fully bring back furloughed or recently redundant workers, let alone take on new apprentices.

But apprentices are a diverse bunch, and as a result have experienced the crisis in vastly different ways: while starts for younger apprentices and especially those at lower levels of study fell away sharply, there was a rise in the number of higher-level apprenticeship starts taken up by those aged 25 and older.

Youth unemployment: Why we need to invest £4.6bn a year

Apprenticeships: How to improve access to level 4

Long read: Stephen Evans and his mission to make a difference

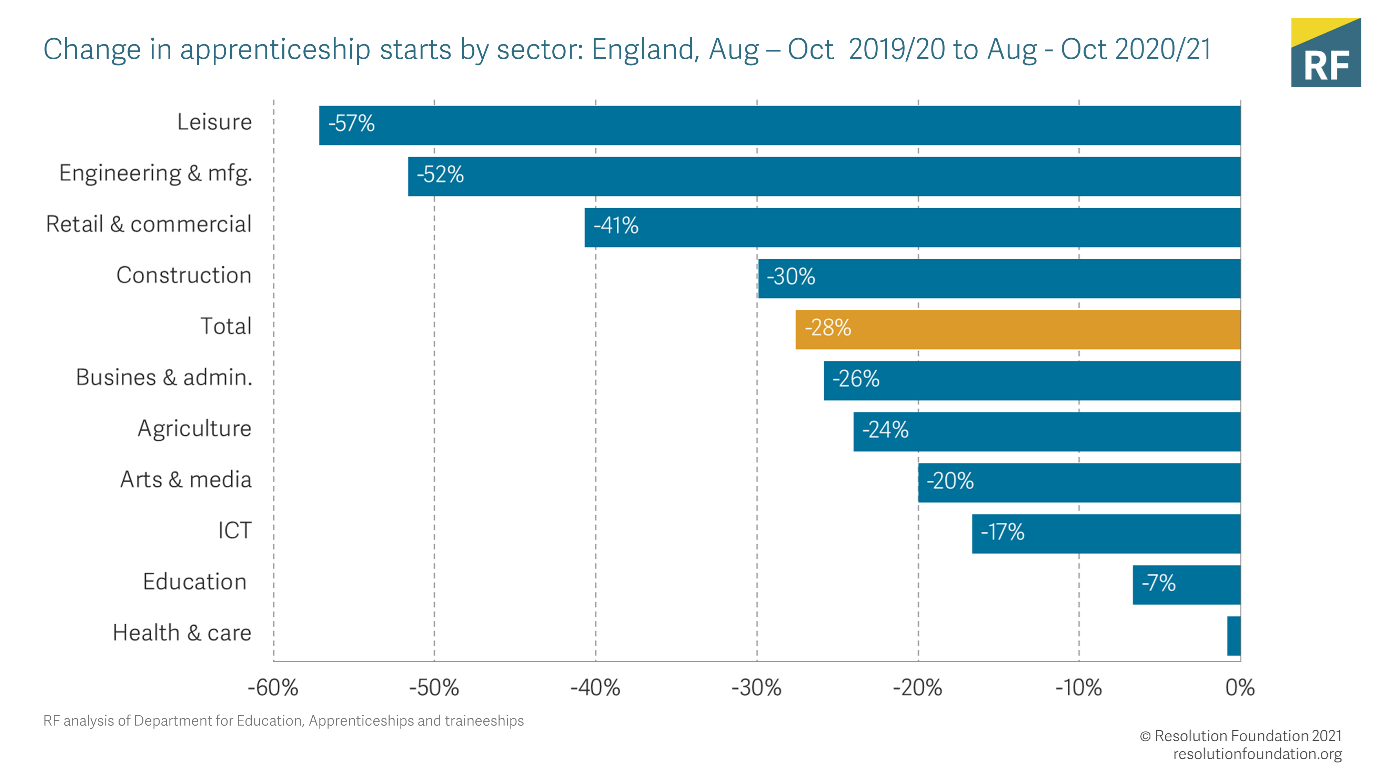

Let’s begin with the headline figures: there were 91,000 starts in total during Q1 2020-21, down 28 per cent from the same time last year. The fall in starts was, unsurprisingly, largest in sectors that have at some point in 2020 experienced a complete shutdown or the effects of workplace social distancing requirements. For example, the fall was largest (-57 per cent) in leisure, travel and tourism, which, despite re-opening over summer, would have remained under some level of supply restrictions.

There was also a substantial fall in apprenticeship starts among sectors that don’t offer in-person services but where it is difficult to work from home (eg, labs, construction sites or factories). For example, starts in engineering and manufacturing fell by 52 per cent. Office-based roles, where homeworking has become commonplace over the past 9 months have fared better, but were still hit: although the overall number of starts fell by 27 per cent year on year, the number of starts in information and communication technology fell by 17 per cent.

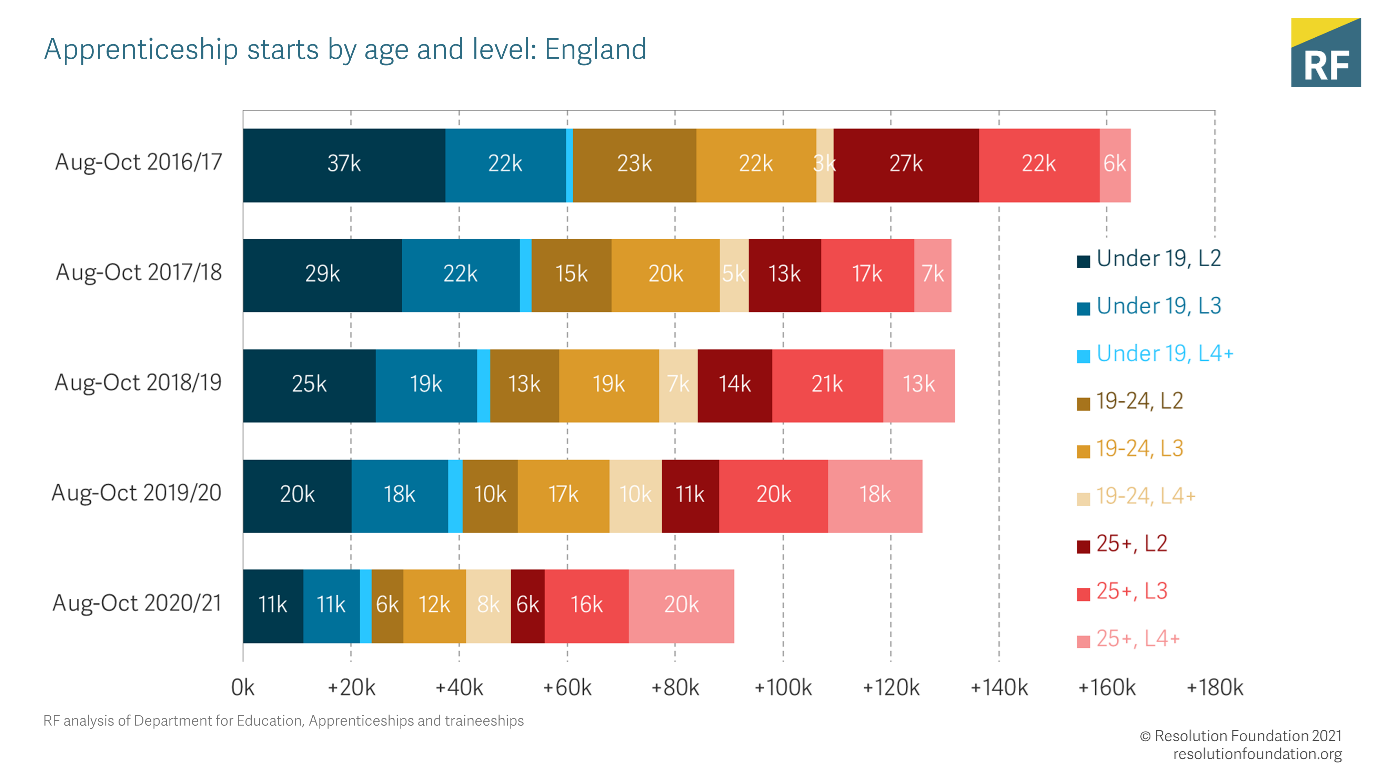

But even before Covid-19 hit, the apprenticeship system had been undergoing a significant (albeit, slower) change: a move away from programmes taken up by young apprentices (ie, those under 25) and at mid and lower levels (ie, levels 2 and 3) towards a system increasingly focused on older apprentices and at higher levels of study. Over recent years, starts at lower levels of study reduced across all age groups, while higher-level starts rose, and in particular among older apprentices - many of whom will not be new starters to their firm.

But even before Covid-19 hit, the apprenticeship system had been undergoing a significant (albeit, slower) change: a move away from programmes taken up by young apprentices (ie, those under 25) and at mid and lower levels (ie, levels 2 and 3) towards a system increasingly focused on older apprentices and at higher levels of study. Over recent years, starts at lower levels of study reduced across all age groups, while higher-level starts rose, and in particular among older apprentices - many of whom will not be new starters to their firm.

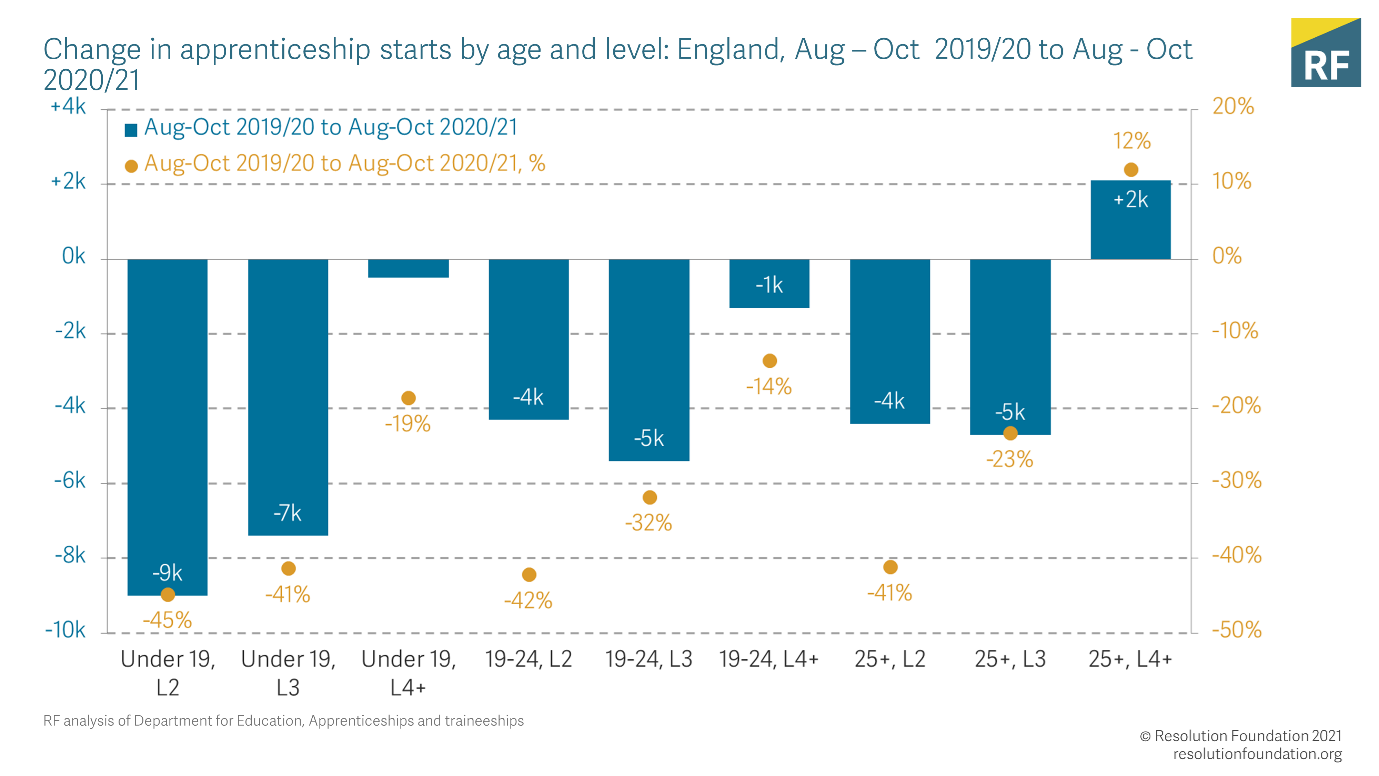

This latest quarter suggests that the Covid-19 crisis has helped to accelerate that shift. Compared with the same period last year, the number of starts taken up by 16- to 18-year-olds during August to October fell by 16,900 (-42 per cent); the number taken up by 16- to 18-year-olds at levels 2 and 3 fell by 9,000 (45 per cent) and 7,400 (41 per cent), respectively. The effects were smaller for apprentices aged 25-plus overall (7,000 or -15 per cent). And although the number of older apprentices at lower and mid levels of study also fell, there was one area in which apprenticeship starts actually grew: the number of higher-level apprenticeships started by older apprentices rose by 2,000 (12 per cent) on last year.

This latest quarter suggests that the Covid-19 crisis has helped to accelerate that shift. Compared with the same period last year, the number of starts taken up by 16- to 18-year-olds during August to October fell by 16,900 (-42 per cent); the number taken up by 16- to 18-year-olds at levels 2 and 3 fell by 9,000 (45 per cent) and 7,400 (41 per cent), respectively. The effects were smaller for apprentices aged 25-plus overall (7,000 or -15 per cent). And although the number of older apprentices at lower and mid levels of study also fell, there was one area in which apprenticeship starts actually grew: the number of higher-level apprenticeships started by older apprentices rose by 2,000 (12 per cent) on last year.

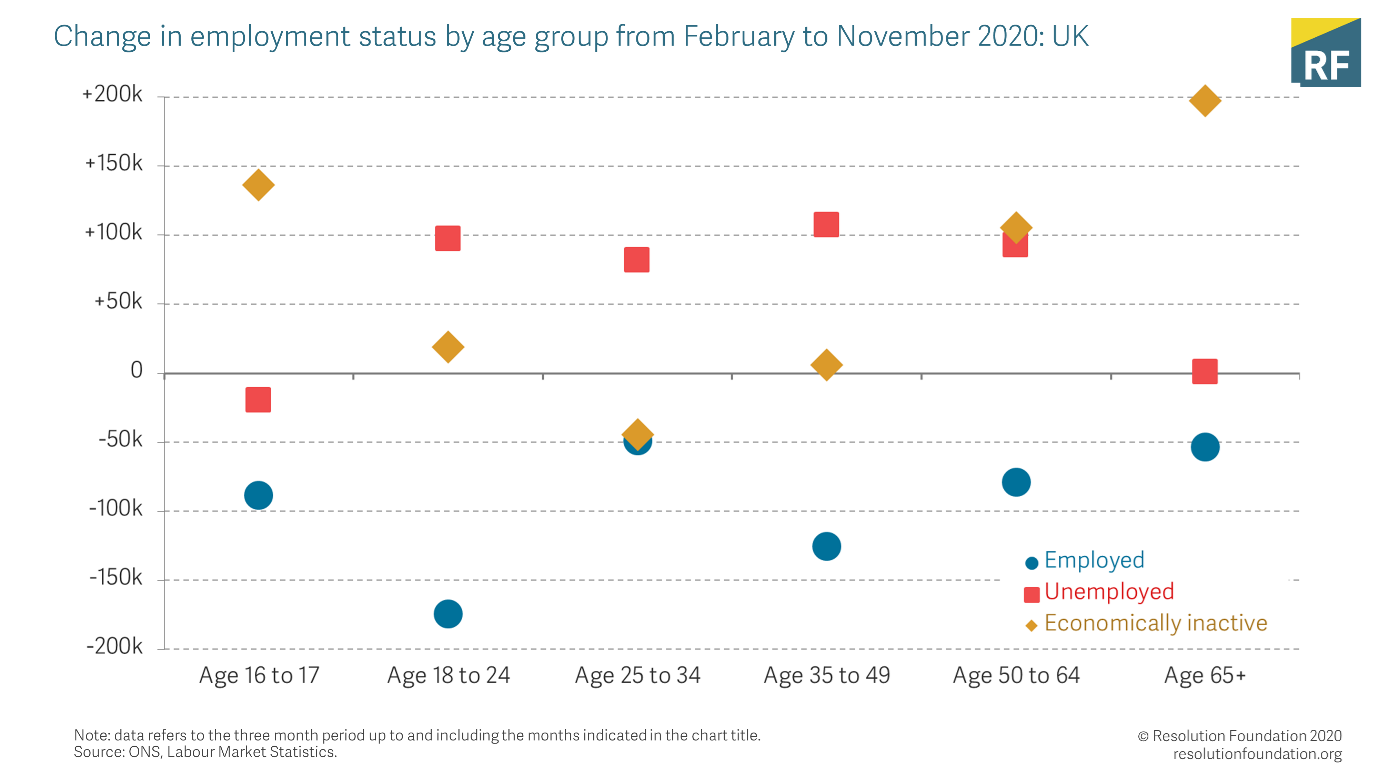

Of course, there’s been a reduction in work and training opportunities for all people, but especially young people, across the wider labour market. Employment figures published by the Office for National Statistics this week show that young people (those below 25) account for around half (46 per cent) of the total fall in employment since the start of the crisis.

Of course, there’s been a reduction in work and training opportunities for all people, but especially young people, across the wider labour market. Employment figures published by the Office for National Statistics this week show that young people (those below 25) account for around half (46 per cent) of the total fall in employment since the start of the crisis.

And although there’s been a rise in the number of young people in full-time study since the Covid-19 crisis began (which will reduce the pool of young people who find themselves unemployed), the actual rate of unemployment has risen 3.5 points (to 25.6 per cent) among 16- and 17-year-olds, and 2.7 points (to 13.2 per cent) among 18- to 24-year-olds. Among 16- to 64-year-olds overall, unemployment rose 1.1 points to 5 per cent. And for many, the effects of unemployment won’t be in there here and now: young people, and especially those with lower-level qualifications, who enter the labour market during a recession and struggle to find a job, will feel employment effects for years to come.

And although there’s been a rise in the number of young people in full-time study since the Covid-19 crisis began (which will reduce the pool of young people who find themselves unemployed), the actual rate of unemployment has risen 3.5 points (to 25.6 per cent) among 16- and 17-year-olds, and 2.7 points (to 13.2 per cent) among 18- to 24-year-olds. Among 16- to 64-year-olds overall, unemployment rose 1.1 points to 5 per cent. And for many, the effects of unemployment won’t be in there here and now: young people, and especially those with lower-level qualifications, who enter the labour market during a recession and struggle to find a job, will feel employment effects for years to come.

All this points to a longstanding (and still growing) need for policy to make sure that young people and especially those with lower-level qualifications aren’t forgotten in the recovery. This means orienting the apprenticeship (and apprenticeship funding) system towards young people and new starters, opening up quality work opportunities such as through the government’s Kickstart scheme and guaranteeing an education or training place for all young people.

Kathleen Henehan is a member of the expert panel for the Independent Commission on the College of the Future and senior research and policy analyst at the Resolution Foundation

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

topics in this article