Diagnosing a crisis of agency

During the last academic year I led a research-informed Teacher Wellbeing programme that took place mainly in government “opportunity areas” across the UK. On a wellbeing programme that is specifically designed for teachers, it would be disrespectful not to talk about the reality of the lived experience of teachers. When doing so, teacher workload and how it impacts negatively on teacher wellbeing was always mentioned. In fact, I regularly heard about a “workload crisis”.

Other themes often appeared when teachers talked about the negative impact on their wellbeing - such as being in a profession where you are continually judged. This not only refers to being judged by peers, or by those in a management position, but also working in a context where there are multiple stakeholders who are quick to judge you as a teacher - even if they have limited knowledge of pedagogy. However, it was the workload crisis that made the most appearances at this stage of reflection.

What surprised me was that when teachers were encouraged to reflect at a deeper level about the workload narrative, and the claims that it was a crisis, workload suddenly became less of a theme and less of a crisis. Why? Well, every narrative contains a meta-narrative that is worth exploring and there is always value in gazing at a problem and asking “what is really happening here?”. This is what the teachers were encouraged to do - and they started to talk about feeling controlled, professionally mistrusted, anxious and fatigued.

My proposition is that the narrative about teacher workload is symptomatic of a meta-narrative that is more profound and far more concerning. This meta-narrative relates to teacher agency. If there is a crisis in the teaching profession, workload is not the real one; the destruction of teacher agency is.

Crisis? What Crisis?

Often in life, the problem is not really the problem. In this decade of austerity, increased responsibility has been systemically squeezed towards teachers. Safeguarding leads and Sendcos are taking on wider social care responsibilities. Teachers and heads are doing the same. It is now possible that one single teacher could be called upon to function as a school-based multi-agency team.

Naturally, all of this is processed as a workload issue as it inevitably results in more work. In this constantly shifting environment, which includes years of government enforced change without consultation, teacher workload presents as the problem - but the increasing lack of teacher agency is the real problem.

The concept of “crisis” emerged regularly in my discussions with teachers. The word “crisis” can relate to situations where there is a critical lack of resources to meet need, or a context where barriers that block our goals can seem insurmountable, or to situations where personal or professional identity (or both) is under threat.

When encountering a crisis people may feel a sense of no longer being able to cope. They may feel hopeless. They may also feel angry. The three most mentioned crises on the teacher wellbeing programme were:

1. The workload crisis

2. The mental-health crisis in the profession

3. The recruitment and retention crisis

I would argue that all three of these crises, be they perceived or empirically supported, are grounded in the most fundamental crisis of all in education - the crisis caused by the continuing destruction of teacher agency. Failure to tackle the teacher agency crisis has huge implications for the future of the teaching profession.

Agency, like wellbeing, is a multi-dimensional construct. Agency, like wellbeing, is relational. It is not something that a teacher carries around with them from classroom to classroom or school to school. Agency is afforded to teachers by the systems and cultures that they exist in, interact with and have influence upon. Being afforded agency gives you feedback about how valued and trusted you are as a professional. One of the main contributors to the devastation of teacher agency is hyperaccountability.

I conducted focus group research with teachers - from all sectors and teaching phases - and they had no major issues at all with the concept of professional accountability. Teachers in this research study understood the need for the profession to be accountable and they saw that accountability increases professional trust. It also increases public trust and elevates the status of the teacher in the public domain.

Accountability systems are often premised on illuminating who is worthy of trust, with what and to what degree. They also aim to shine a light on who cannot be trusted. In the context of education, accountability raises questions about, for example, who can and cannot be trusted to raise education standards, keep children safe or teach what is deemed to be relevant in terms of knowledge, values and skills. Accountability systems prioritise and promote certain ways of being, knowing and behaving.

However, over the years, accountability has gone hyper and teachers now live in a hyperaccountability landscape. Yes, it is important to collect data and use it for a purpose, such as understanding and mapping pupil progress, but hyperaccountability systems can produce data fetishism and teacher creativity can become restrained.

If allowed to continue, hyperaccountability in education could lead us to the day when important factors that influence pedagogy, such as compassion and relationships, become so undervalued that teaching will be reduced to a mechanistic technical activity that is focused on delivery: no relationship building needed, no empathy required, no qualifications necessary, just broadcast what children and young people have to learn.

Hyperaccountability has real-world consequences, too: critical friends can start to be perceived as critical enemies. Hyperaccountability makes the choice to apply for a job in a school that Ofsted has judged as “requires improvement”, or put in special measures, unattractive or off the radar for some teachers who might be an exceptional asset in such a school context.

If you are a teacher, it is entirely natural to feel de-professionalised when you spend more time justifying that you can do your job rather than, for example, being funded, supported and enabled to develop and grow within your job. Engaging in a series of compliance-creating, hoop-jumping tasks that make you feel that your professional knowledge, status, judgement and experience are being undermined is one outcome of hyperaccountability - it is also not in my top 10 suggestions for improving teacher agency or teacher wellbeing.

Teachers can and do get worn down and burn out. Hyperaccountabilty fatigue becomes real when teachers find themselves in a situation where their lived experience becomes incompatible with what they believe “being” a teacher actually means - and is radically different from what they wanted and expected when they initially entered the profession. It is time for hyperaccountability to be challenged and halted. A more mutual and respectful system of accountability is needed, one that validates and trusts teachers as professionals.

Collaboration as a way forward

Perversely, a UK education system that apparently intends to create school autonomy is actually destroying teacher agency in the process. How can competitive comparisons between schools increase their agency and empower rather than divide them?

Surely schools collaborating more, with external agencies such as Ofsted supporting them in doing so, would increase both teacher agency and school agency and halt the advance of the winners and losers culture that currently exists - a culture where headteachers can be treated like disposable football managers. Surely collaborative approaches can increase inclusion and reduce the need for insidious practices such as exclusion via “off-rolling”. Surely, in the planning meetings about creating greater school autonomy, someone should have suggested that the Department for Education focuses on creating greater agency instead. Autonomy is not agency. Surveillance is not support.

A crisis, be it real or perceived, presents tensions and dilemmas that must be confronted and resolved. To resolve a crisis, decisions must be made. Teachers are already making decisions and many are voting with their feet and leaving the profession, especially in the first five years of teaching.

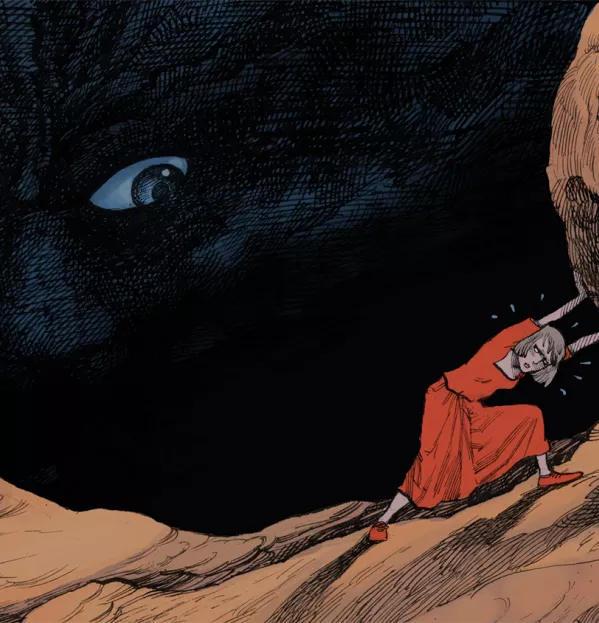

The agency crisis is a crisis of being. It is not just about what teachers do, it is about what it means to “be” a teacher. Lack of agency generates anxiety. Psychologically, free-floating anxiety generates fear. As teacher agency crumbles, the system has to manage the anxiety and fear that is generated within the system and projected back into the system.

One task that the DfE must tackle is to understand, manage and eliminate the free-floating anxiety and fear that is inherent in the education system and replace it with professional pride and confidence. Increasing teacher agency and improving teacher wellbeing will enable this to happen. Otherwise, the education system will break - as will even more teachers who work within it.

Dr Tim O’Brien is visiting fellow in psychology and human development at UCL Institute of Education. He tweets @Doctob

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters